The First Worldwide Festival of Resistance

Print This Print This

By Mackenzie McDonald Wilkins, Popular Resistance

Popular Resistance

Monday, Jan 26, 2015

|

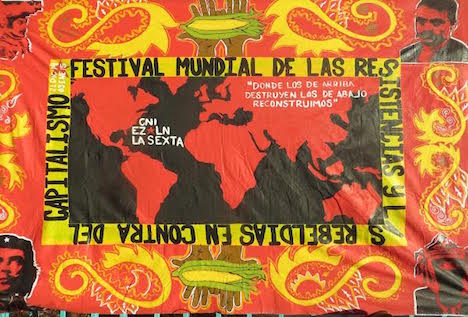

| Sign for the first Worldwide Festival of Resistances Against Capitalism. |

From December 21, 2014 through January 3, 2015 some 2,600 people from 48 countries (2,050 from Mexico and 550 from other countries) gathered for the first Worldwide Festival of Resistances Against Capitalism.

The festival took place all over Mexico and the majority of participants travelled together in a mass caravan of buses (not without mechanical problems and police interference) to the different regions to share and listen stories and strategies of resistance, to strengthen their cultures of resistance, and to build lasting networks locally, regionally, nationally, and globally. Thanks to the excellent organizing by EZLN and CNI the impacts of the festival will reverberate amongst the participants and their resistance communities for years to come.

The event, organized by the Zapatista Army for National Liberation (EZLN) and Mexico’s National Indigenous Congress (CNI) consisted of: an opening in San Francisco Xochicuautla on December 21; comparticiones or sharings in the communities of Xochicuautla and Amilzingo on the 22-23; the grand cultural festival in Mexico City on the 24-26; continuation of sharings in the community of Monclova Candelaria on the 28-29; festival of rebellion in the Zapatista community of Oventic on new years night; conclusions, next steps, and declarations at University of the Earth (CIDECI) in San Cristobal de las Casas from the 2-3 of January.

|

| Bicimaquina (bike powered blender) at festival in Mexico City. |

Communities Standing in Defense of Their Right to Self-Determination

Events began in the indigenous community of San Francisco Xochicuautla. Xochi, as the community is often called, is a stronghold of Ñätho language and culture. People that I met from Xochi are proud of their history, their culture and language, their beautiful forests. All of this is threatened by a highway that is being built through their communally owned ancestral lands, without their permission. The Toluca-Lerma highway, largely built to advance industry, is destroying the forests, agricultural areas, and waters of Xochi. Fields of a unique variety of ancestral blue corn, the basis of the local diet, are being bulldozed over–another species of corn and another people threatened by the onslaught of capitalism and industry.

The community stands in defense of its right to self-determination, a right that was maliciously usurped by invading developers. The community is self-governed under the indigenous usos y costumbres system in which decisions are made collectively through large community meetings, called general assemblies. A community member told me, “the system was betrayed by developers who paid off two community leaders. They were paid 40,900 pesos [$2,920] each to sign away the community’s ancestral rights.” She sighed, “how could they do this? We decided in assembly to say no!” The people are fighting back, and have allied with at least 10 other impacted communities. In Xochi alone there have been at least 15 community members arrested for protesting, some standing directly in the way of construction, others illegally imprisoned for an extended period. The project continues with President Peña Nieto’s full support. At the festival people chanted to the people of Xochi: “¡No están solos, no están solos!,” “You’re not alone, you’re not alone!” And, as more people and communities shared their stories, this became evermore clear.

Resistance to mega development projects, like the highway through Xochi, were a common theme at the festival. We heard from communities in Mexico fighting against mines (gold, silver, copper, etc.), dams, fracking and other fossil fuel infrastructure, plantations, logging, large wind and solar farms. All of these projects (including the wind/solar developments) displace local and indigenous communities, often destroying their way of life, and disrupt, ultimately demolishing, fragile ecosystems. They are done without free, prior, and informed consent of the communities, supposedly required by international law (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People). Sadly, the multinational corporations running these projects, not people or nature, are the ones with rights, especially under free trade agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Those who resist are brutally suppressed, and are commonly kidnapped and murdered by the Mexican government.

|

| Sign welcoming families of Ayotzinapa 43 |

Families Seeking the Disappeared and Justice for the Murdered

Police violence was another overarching theme of the festival, with a particular focus on the September 26 Ayotzinapa murders and disappearances in the town of Iguala where police started firing on student buses during a protest. Six students were killed and 43 were kidnapped and disappeared. The students, from the Ayotzinapa Normal School, were protesting poor school conditions and were trying to raise money for travel to the annual march in Mexico City to commemorate the 1968 student massacre. A mother of one of the students told of the schools: “they have crumbling walls, no books or pencils, too few desks, and its all getting worse.” She said, “they weren’t protesting because they wanted to. They were protesting because they needed to.”

Since Mexico’s war on drugs began in 2006 there have been at least 40,000 people killed in the country. Many of these deaths are, contrary to police reports, unrelated to drug trafficking. Largely, they are attacks on civilian protestors and indigenous peoples. Unlike other disappearances and massacres, Ayotzinapa has gained national and international attention because of the popular uprising in response, largely led by family of the dead and disappeared.

|

| Performance with chairs for the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students. |

Family members of the disappeared and survivors of the attack have been traveling around the country in search of their loved ones. They share their story and organize wherever they go. They were special guests at the festival and helped organize a march of many thousands in Mexico City on December 26th. The message was simple: “¡Vivos se los llevaron, vivos los queremos!,” “They were taken alive, we want them back alive!” Parents, brothers, sisters, sons and daughters were clearly in great pain, but hope their loved ones may still be alive. While their search continues, they fuel a growing anti-government movement, not just against Peña Nieto’s regime, but all political parties, violent by nature. They ask communities to kick political parties out of their local politics and they ask people not to vote in the upcoming elections, both ways to de-legitimize top-down government. Instead, they are allied with the EZLN and CNI in seeking a world constructed from the bottom up.

Celebration of Life and Dignity

The festival in Mexico City was a large celebration, a celebration of life and dignity in the face of atrocity from above. The event took place in one of the poorest parts of Mexico City’s endless sprawl at the Lienzo Charro ranch. It began on a rainy Christmas Eve day. Neither the rain nor the holiday prevented large crowds from gathering and participating in workshops, dancing, music, independent movie screenings, mural painting, a makeshift tattoo parlor, soccer and chess tournaments, or enjoying tamales and drinking atole.

|

| Sharings in Monclova. |

Three large canvass tents were set up, providing some shelter. Hundreds of vendors, representing different indigenous communities and activist collectives, huddled under one of the leaky tents, selling and gifting organic food, artwork, handmade jewelry, colorful clothing, blankets and ponchos, vegan boots, movies of uprising, anarchist and indigenous literature, and a maze of other merchandise. Under the other tent people gathered for workshops and art classes such as: community cartography; relationships of liberty and autonomy; solidarity economies, community money, and time banks; ecological toilet construction; ecological home construction; what to do when arrested; urban food sovereignty; making chocolate; traditional Mexican medicine; screen printing; stencil; clay sculpting; painting; and many more. There were also two stages with a variety of live music and dancing throughout the day. Others sat around playing drums, strumming traditional string instruments, singing songs of revolution and life in the campo.

Fighting Privatization of Electricity

From Mexico City we headed to Monclova, a rainforest community in the state of Campeche. Monclova is fighting against the privatization of electricity that is raising costs and cutting their already minimal services.

Five community members were imprisoned for 11 months from 2009-2010. Community members I spoke to talked about the rich ecosystem in which they live, right along a meandering crocodile-filled river and extensive wetlands, with pre-Hispanic ruins nearby.

We arrived in the morning after an overnight bus trip. Bucket baths were set up near the river and breakfast of rice, beans, tortillas, chiles, and tea or coffee was served by the community. Sharings were held outside under a beautiful forest canopy. It started raining and everyone ran for their tents.

The next day people huddled under a large circus tent to listen. We heard about struggles for land and justice around the country. We heard about other cases of police violence. We heard about indigenous communities trying to hold onto their culture and language, in the face of Mexico’s modernizing and whitening agenda. We heard about history, about the 1968 massacre, the Mexican Revolution, and the 500 years of resistance to colonialism, capitalism, and other evils brought by the West. We heard endless stories of exploitation, violence, and displacement related to mega development projects or encroaching tourism. Even kids came to speak. One talked about about leading marches, a culture of life to fight the culture of death, and building a new world from within his community.

|

| Celebration in Oventic |

Mexico’s Heart of Resistance

After two nights in Monclova, our caravan headed to the final region, the central highlands of Chiapas Mexico. We were based at the University of the Earth (CIDECI) in the town of San Cristobal de las Casas. The area surrounding San Cristobal has the country’s most concentrated indigenous population and is Mexico’s heart of resistence.

Reforms of the Mexican Revolution, like the 1917 constitution’s article 27 that protected indigenous communal lands (ejijdos), never reached Chiapas. Throughout the 20th century indigenous communities continued to be persecuted, their lands stolen and exploited by large landowners. As roads infiltrated the rural state, huge areas of old growth forest were cut down, cattle ranching became a large business, and tens of thousands of small indigenous landowners were displaced, though not without a fight. In the early 1980s Chiapas was further militarized by its governor, General Absalon Castellanos Dominguez, during whose administration, “102 campesinos are assassinated, 327 disappear, 590 are imprisoned, 427 are kidnapped and tortured, 407 families are expelled from their homes, and security forces overrun 54 communities” (Hayden, 2002).

In 1983, in the midst of these atrocities, the Zapatista National Liberation Army was formed by a few Mexico City college professors from the National Liberation Front (FLN) and a few indigenous leaders from Chiapas. By 1989 the Zapatistas had entered upon invitation into numerous indigenous communities and had an armed force of at least 1,300. This army continued to grow in the years before the revolutionary article 27 was repealed in 1992, for many the last hope of owning land. The EZLN buckled down, preparing for a fight, even a revolution. They knew that article 27 was repealed for a reason. Another forced displacement of indigenous communities from their lands was preparation for the neoliberal takeover under NAFTA–it would ease the opening of new markets.

But, on January 1, 1994, when Mexico joined the United States (Clinton administration) in this corporate coup, the EZLN occupied six large towns and hundreds of ranches in an armed uprising against 500 years of colonialism. They would not stand aside as global elites celebrated new freedoms and the onslaught of capitalist globalization. Another world was possible. President Salinas did not agree, and responded with a military assault, bombing nearby indigenous communities, killing at least 145. Soon there was a cease fire, but the EZLN did not go away.

Building New Communities Based on Self-Determination and Autonomy

To this day, much of the originally occupied territory is under the control of the Zapatistas and they are proving that another world is possible, that a large area, high in cultural and ecological diversity, can be self-governed in a non-hierarchical, non-capitalistic, non-patriarchal manner. That it can be done according to principles of respect, for each other and the natural world, and cooperation, not exploitation and competition.

|

| Workshop on ecological homes. |

The Autonomous Zapatista Communities demonstrate how autonomy and self-determination can work as a lifestyle, economy, government, and form of resistance. The Zapatista communities are based around five regional political and cultural centers called caracoles. These are the seats of the buen gobierno (good government) and are spaces for gatherings, like this year’s 21st anniversary celebration of the uprising. All Zapatista municipalities and independent communities belong to one of these caracoles.

The communities function democratically with decisions made through general assemblies in which women and men have an equal say. Women’s participation in Zapatista assemblies is unique. Other indigenous communities with a similar system of participatory self-governance, usos y costumbres, are often male-dominated.

Zapatista communities do not accept programs from the Mexican government. Instead, they are in charge of their own food and resources, education, healthcare, legal system, economy, politics, and ultimately their lives. On Zapatista territory there are no mega development projects like those becoming more and more common throughout Mexico. They take care of the land and protect its life-giving force. Deforestation, water and air pollution, genetically modified crops are anomalies on Zapatista lands. Their territory is perhaps safer from ecological destruction than anywhere else in Mexico. Likewise, indigenous cultures and languages thrive in the region and they are consciously protected and enhanced. Zapatista communities reject the Mexican state’s modernizing program to assimilate indigenous peoples into the national character, largely run through state schools.

The area continues to be heavily militarized with paramilitary and counterinsurgency bases surrounding the autonomous region. On May 2, 2013 an indigenous school teacher of the Escuelita Zapatista, José Luis Solís López otherwise known as Galeano, was macheted and shot to death by paramilitary forces. EZLN leader Subcomandante Moisés lamented the loss during a speech in the caracol of Oventic, outside of San Cristobal.

The Zapatista community of Oventic hosted the new years celebration on the 21st anniversary of the uprising. The festival caravan arrived on December 31st, joining thousands of people from surrounding communities, the majority of whom wore the classic Zapatista black ski mask, a red star, and a red scarf or bandanna. There was food, music, and dancing, but no drugs or alcohol, all night long. We returned to University of the Earth the next morning and stayed until the end of the festival on January 3rd. This is where we worked on conclusions, next steps, and a final declaration, summarizing the politics of the festival.

|

| Ayotzinapa families on stage carrying photos of their dissapeared relatives. |

Can the Culture of Resistance Save the Planet

We all live on the same planet. It is our only home and it is being systematically destroyed by industrial civilization and global capitalism. People everywhere are suffering the consequences, but are in resistance. As we move further into the 21st century how will these struggles play out? As a global resistance movement will we be able to fight back encroaching destruction before it is too late? Will we be able to build a world, as the Zapatistas suggest, in which many worlds fit? Will we be able to reclaim democracy, justice, and autonomy from the powers that be?

During the festival of resistance we learned about the inevitable horrors of ongoing capitalism, the destruction of remaining ecosystems, the continued genocide of indigenous peoples, about global state violence against people. We also learned that people everywhere are fighting back, even when it means putting our lives on the line.

One of the most common responses to speakers was a chant from the crowd that they are not alone. That we are all in this together and are fighting the same fight. And, as the relatives of the Ayotzinapa massacred say, we cannot sleep until we defeat these evils. ¡La Lucha Sigue! The Fight Goes On!

|

Print This Print This

|