Women of Afghanistan: Episode 1 - Sparghai Basir Aryan

Print This Print This

By Sparghai Basir Aryan, Sahar Speaks

Huffington Post

Tuesday, Jun 28, 2016

Kabul in 1979 and 2016: A Mother and Daughter Reflect on Change

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, beginning 36 years of continuous war and conflict. Here, 26-year-old writer Sparghai Basir Aryan compares her life in war-torn, oppressive Kabul with that of her mother, who lived peacefully and enjoyed wearing skirts and no headscarf, something unheard of today. The women have much in common: both studied at Kabul University and worked for Save the Children. But war made their lives dramatically different.

My mother, Ghuncha Basir (her first name means the bud of a flower), 1979

It is my first time in Kabul. The bustling capital is different from my poor village, Qalatak. In the Pashayi language, the name means “a small village.” On a map, it’s hard to find, hidden among eastern Afghanistan’s high mountains.

I’m one of the few girls from Qalatak to attend university. My mother died when I was only 6, but I know she would be proud. My father, one of the most educated men in the village and a former school teacher, can’t stop beaming. Neither can I.

I haven’t been able to sleep for the past week – I’m excited by everything I want to learn. Because Kabul is more expensive than my village, I am working part time at Save the Children as a nutrition field worker. We go to the outskirts of the city and check children for malnourishment. We give them advice and some biscuits and milk.

The electronic bus system is so interesting! And easy to use. For a village girl, it’s all so exciting. The bus driver and cleaners are ladies. They wear tight jeans, and their long straight hair winds down their backs. I love watching them.

I spend most of my days reading books by my favorite Russian author and political activist, Maxim Gorky, at the big, sprawling university library. I’ve chosen a perfect outfit to wear for the first week of school: a purple skirt that covers my knees and a tight, white, sleeveless blouse. Oh, and how could I forget my purple heels. I'll wear them with no socks.

I am so excited. One day, my daughter will walk on the freshly-cut green grass of this university.

The future is so bright.

My mother, Ghuncha, 2016

It’s hard to imagine I had no fear at that time, in the 1970s. Was I so naïve to think that my daughter Sparghai – which means ‘spark’ in our native Pashto – would follow in my footsteps?

That she would live in a country of opportunity? Not one of restriction?

That she would be able to walk on the same freshly cut green grass that my sandals and high heels grazed? That she would be able to participate in political protests like I had? That she would be able to wear her favorite dress or skirt in public? That she – and I – would live without fear?

How has everything turned out to be the opposite?

I, Sparghai, 2016

When I look out of my window at the University of Kabul, I see big cement walls. They are everywhere. They are in front of government buildings. They are in front of most buildings. They are meant to keep those inside safe and separate from what is on the other side. But how long does it take before walls crush our own sense of identity?

I’ve never been able to wear a skirt or a dress on The University of Kabul’s campus. My mother used to spend days lazing in the green fields of the campus in her jeans. I can only wear jeans in my house. In fact, I’m not allowed to wear anything that shows part of my body. My legs must be totally covered. Every day, I cover my head so nobody sees my hair. Still, I receive disgusting comments from men.

If I wore what my mother wore in the 70s, I’d face serious threats. I could even be killed by some segments of society. This is sadly all too common in my country.

|

| Ghuncha had this photo taken in a Kabul photography studio in 1979. Ghuncha studied at Kabul University, majoring in biology. |

The electronic buses my mother used were destroyed when civil war broke out in Kabul, in 1992. Now, if a woman drives in Kabul, water or Pepsi are thrown at her. That’s why women never drive with the windows down.

Like my mother, I too work at Save the Children. But my job is harder than it was for my mom. I research community-based education. There are no preschools in Afghanistan. When I go to the field to conduct research, I wear a long black head and body covering. And still, I receive scornful looks. Eyes tell me I shouldn’t be out in public. That I shouldn’t be working, that I shouldn’t be – period.

|

| Sparghai’s university ID photo, taken in 2007. Like her mother, Sparghai studied at Kabul University, but majored in sociology. At the Kabul photography studio where this was taken, she was told to cover her head with a scarf. |

As my mom said, it wasn’t supposed to turn out like this. Not for a daughter and a country born by fierce struggle, resistance, and a bold fight for freedom.

The night my parents got married, in 1984, fire and bombs lit up the sky. Afghanistan was fighting the Soviet occupation. My mother was a revolutionary. On the night my older sister was born, there was heavy rain. Large, wet drops covered our whole village. She was born near a mountain that would soon be attacked by the Russian military. They named her

Saman, the name of that mountain. They had to flee. My parents bundled my sister up and walked through high, treacherous terrain. Eventually they made it to neighboring Pakistan. They soon settled into a refugee camp east of Peshawar city.

In December 1989, I was born in the camp, the fourth of five children. We were so far from the Kabul my mother always talked about. My uncle named me Sparghai, meaning sparks of fire. They wanted me to bring light to our society.

My childhood was tough. I grow up in the muddy houses and dusty streets of the Khewa refugee camp. Before I was born, my mother started The Naseema Shaheed High School, named after my paternal aunt who was killed by the Russians, resisting their occupation. My mom taught in the school for 20 years and I’m a graduate. Eventually, the Pakistani government destroyed the school and the entire camp, saying that refugees should go back to their country.

When I was a child I didn’t know about my country, my homeland and my people. I was introduced to Afghanistan through the words and memories of my mother. In vivid detail, she would sketch the beautiful streets she used to walk in, her interesting classes, all her girlfriends.

But she always used the past tense. I soon realized that the Kabul she was describing no longer exists.

When the U.S. ousted the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, in 2001, I was joyous. Finally, I would see the country my mom had described.

|

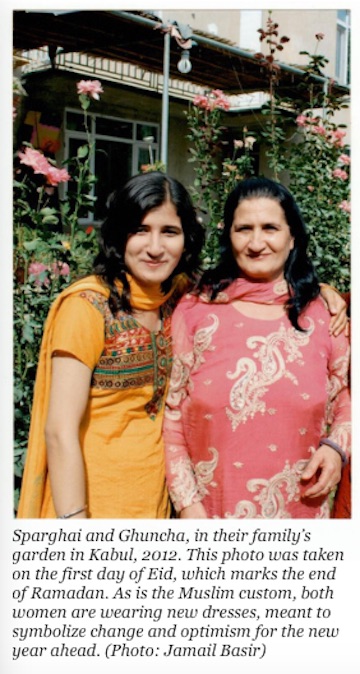

| Sparghai and Ghuncha, in their family’s garden in Kabul, 2012. This photo was taken on the first day of Eid, which marks the end of Ramadan. As is the Muslim custom, both women are wearing new dresses, meant to symbolize change and optimism for the new year ahead. (Photo: Jamail Basir) |

In 2005, when I was only 15, my father took us to Kabul. My eyes almost shattered. Four years had passed since the fall of the Taliban regime, and almost everything lay destroyed. Still, there was hope. Hope that the government would rebuild the hospitals, roads, and schools. A fresh start. That’s what we all wanted. While it wasn’t the Kabul my mother lived in – her classrooms are now pockmarked with holes from bombs – I fell in love with the mountains surrounding Kabul. They are crammed full of houses. During the velvet night, they appear like light boxes.

Soon, I began university in Kabul, choosing to major in social studies to learn about a country I was still getting to know with my own eyes. It wasn’t long before I realized things might not turn out the way we wanted. That peace would still be elusive. That people would still run through the mountains to seek a better life in another country.

For one, the Taliban hadn’t really lost power. That means I hear comments like: “God Bless the Taliban! They are great for not letting women out of their homes!”

Then, there’s the everyday battle of walking down a street. At all times, you’re judged. And when you’re a woman, you’re judged simply for breathing.

And it’s not just the Taliban or conservatism one fears. NATO convoys have large men in black sunglasses brandishing Kalashnikovs.

When I was growing up as a refugee in Pakistan, I was an immigrant, an outsider. Pakistanis would shout “mahajar” at me, which means “the immigrant.” I thought those days of feelings like an outsider were behind me when I moved back to my motherland.

But not a day goes by that I don’t feel like an outsider, an immigrant to my own country. This is not the country my mom told me about every morning as she made tea, every night as she tucked me into bed.

When will we be able to have the lives we want and not the lives we flee from? When will Afghanistan become my – our – country again? When will I be able to lay in green fields, gazing up at the big sky as if it wants me there?

|

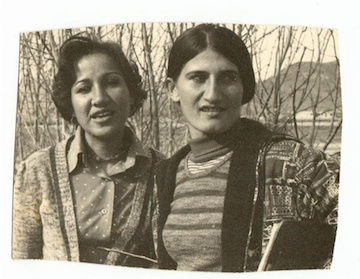

| Ghuncha (right) and her friend Nadia. This photo was taken in 1977 in Musahe, in Logar Province, while the women were working for Save the Children. Today, the village is extremely dangerous for those working at foreign organizations. Nadia fled war and now lives in Canada. (Photo courtesy of Save the Children) |

Source URL

|

Print This Print This

|