|

After nearly two decades of futile searching for a vaccine against the AIDS virus, researchers are reporting the tantalizing discovery of antibodies that can prevent the virus from multiplying in the body and producing severe disease.

They do not have a vaccine yet, but they may well have a road map toward the production of one.

A team based at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla reports today in the journal Science that they have isolated two so-called broadly neutralizing antibodies that can block the action of many strains of HIV, the virus responsible for AIDS.

Crucial to the discovery is the fact that the antibodies target a portion of HIV that researchers had not considered in their search for a vaccine. Moreover, the target is a relatively stable portion of the virus that does not participate in the extensive mutations that have made HIV able to escape from antiviral drugs and previous experimental vaccines.

"This is opening up a whole new area of science," said Dr. Seth F. Berkley, president and chief executive of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, which funded and coordinated the research.

| See the Scripps Research Institute press release, Two New Antibodies Found to Cripple HIV |

At least 33 million people worldwide are infected with HIV, and at least 25 million have died from AIDS, according to the World Health Organization. Two large trials of experimental vaccines have failed -- the most recent, in 2007, because the vaccine apparently made people more susceptible to infection.

To find the neutralizing antibodies, researchers collected blood samples from more than 1,800 people in Thailand, Australia and Africa who had been infected with HIV for at least three years without the infection proceeding to severe disease. Such individuals are most likely to produce antibodies that interfere with the replication of the virus.

Researchers at Monogram Biosciences in South San Francisco studied the samples most resistant to infection, then a team from Theraclone Sciences in Seattle isolated the antibodies responsible for the resistance.

They ultimately isolated two antibodies, called PG9 and PG16, from one African patient. The antibodies were able to block the activity of about three-quarters of the 162 separate strains of HIV they tested it against.

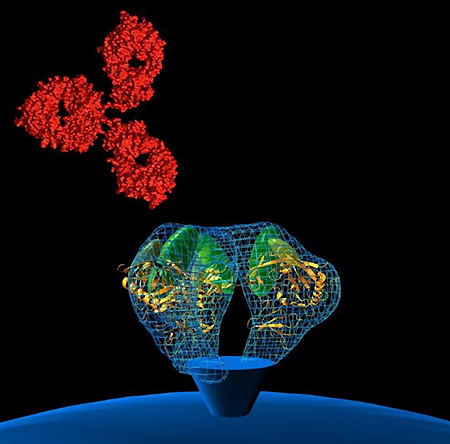

Immunologist Dennis Burton of Scripps and his colleagues then showed that the antibodies bind to regions of two proteins on the surface of the virus, called gp120 and gp41, that help the virus invade cells. These regions had never before been considered as targets for vaccines.

Researchers still have a long way to go to produce a vaccine, however.

The antibodies themselves could potentially be used as a treatment for infected patients who develop severe disease.

But the long-term hope is to find molecules, either synthetic or natural, that can stimulate the body to produce the broadly neutralizing antibodies. Such molecules could potentially be the basis for a successful vaccine.

Los Angeles Times