The Afghanistan that Lindsey Graham, Joseph Lieberman, John McCain and seemingly countless other politicians have been visiting at taxpayer expense recently might as well be on Mars, so different is it, apparently, from the Afghanistan that Jean-Claude Muller, special councilor for international cultural matters to Luxemburg’s prime minister, Jean-Claude Juncker, and I visited just this past month.

As professional linguists, we were ostensively doing linguistic field work in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor (we are researching a book provisionally entitled “The Tongues of the Taliban: How They Get Their Intelligence”). We funded the expenditure ourselves, and as linguistic researchers have no particular political axes to grind.

|

The Wakhan Corridor is that strange-looking panhandle in far northeastern Afghanistan that is strategically sandwiched between Tajikistan to the north and Pakistan’s awesomely snow-bound Hindu Kush to the south and that also abuts briefly and precariously on China. It is a demilitarized-zone creation of the 19th century Great Game that was viciously played out between Imperial Russia and the British Empire. It is an arbitrary creation and therefore geographically reflects the roots of many of modern Afghanistan’s current ills.

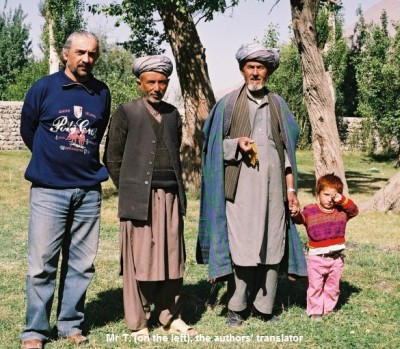

We entered Afghanistan from Tajikistan by walking unescorted across the no-man’s land at the Oxus River border station at Eshkashem. We were dressed as civilians and carried our own packs: no vehicles, no flak jackets, no body guards, just plain folks. We were, however, accompanied by our impressive guide and translator, whom we shall simply call Mr. T., a Tajik native of Khorug and a speaker of Tajik and Russian (he spent four years studying film at the academy in Moscow and, like all other Tajiks in his age group, served in the Russian army), as well as Dard; but his native language is Shugni, which is also widely spoken across the Oxus from Khorug in Afghanistan, as is Tajik: there are as many Tajiks (four and a half million) in Afghanistan as in Tajikistan. Then, too, Mr. T. had spent eleven years in Afghanistan working for Focus.

|

Clearly, we had all the advantages over “official” visitors pointed out by Joseph Kearns Goodwin in his “Afghanistan’s Other Front” and then some: not only could we move about freely as civilians in an ordinary van with an Afghan driver and thus be far less “likely to intimidate and more likely to elicit candor” than highly marked official visitors, the very advantages Goodwin stresses, but we also had one-on-one conversational access and abilities, something our military and politicians have woefully lacked for decades.

The Wakhan Corridor is a heady ethnic and linguistic mix coupled with profound religious differences: Ismailis fervently loyal to the Aga Khan, the 49th Imam, who saved them from certain starvation during the civil war in Tajikistan; Shiites; covert Buddhists; remnants of pre-Islamic paganism reminiscent of that in Ladakh and Nepal; and even vestiges of Zoroastrianism. And this corridor is what all of Afghanistan might have been and might still hope to be: safe and pleasant, even if initially dirt poor, with no evidence of a Taliban or al Qaeda and devoid of the corruption and rampant system of bribes that plagues the rest of the country. Then, too, we saw no poppies in the Wakhan Corridor, and we walked many fields.

|

The answer to the the questions of what to do about the rampant corruption on the one hand and the Taliban/al Qaeda on the other hand that plague Afghanistan … and the answer to these questions is clearly not more boots on the ground (just ask the Russians about that one … with an estimated cost of some $82 billion and the loss of their empire; though you can’t very well ask the 16,500 British troops slaughtered at the Khyber Pass in just one engagement in 1842, and the Brits didn’t get the message until the disastrous Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919) or elaborate training programs (Anti-bribing 101?) or monitoring all those police checkpoints where palms are greased, lies within the Wakhan Corridor itself and just across the Oxus River in Tajikistan’s Autonomous Gorno-Badakhshan Region, still known by its Soviet abbreviation GBAO.

The GBAO is just as culturally and linguistically heterogeneous as the Wakhan Corridor, if not more so. But once you leave the bribe-free GBAO, for which a separate visa is required in addition to that for entering Tajikistan, the police checkpoints and corruption start all over again: drivers from the GBAO are routinely racially profiled by Dushanbe’s traffic cops and required to hand over bribes. Once I convinced our Kyrgyz driver to trade his skull cap for my baseball cap, we started being waved past Dushanbe’s checkpoints.

In the end, it was Tajikistan’s disastrous civil war that raged for five years from 1992 until 1997 and that claimed more than 60,000 lives and uprooted more than a million refugees that left the GBAO independent, proud, united and with a clear and collective vision for a future, a vision that finally sees prosperity within its grasp from increased tourism and from providing a trade corridor for neighboring China; the Pamirs are set to become the hub of a new Silk Road, and, get this, it is the Chinese who are building the road system (lamentably with their prisoners, of which they have millions, who receive only food and lodging for their efforts).

|

Afghanistan per se is a fictitious socio-political unit that, by and large, was engendered in the wake of the 19th century’s Great Game; any resemblance to Iraq is real. As we see it, given the successes of the Wakhan Corridor and the GBAO, an effective solution to current woes would be to convert Afghanistan into a federation of largely autonomous “cantons” divided along ethno-linguistic lines (and even those of religious persuasion) and then encourage cross-border communication and cooperation between and among related groups; so, for example, between Tajiks on both sides of the Oxus River divide, between Belochis on both sides of the Afghan-Iran border, and so on.

We should also look for creative and novel non-military solutions such as replacing poppy cultivation with saffron cultivation (virtually economically equivalent crops), encouraging local handicraft co-operatives, whether operated by women or not (as has been successfully done in the GBAO), building rural schools along the lines of Greg Mortenson, engaging a variety of non-military players such as His Highness the Aga Khan in socio-political decision making, and so on. And we should largely absent ourselves to let Afghan diversity flourish once again. Going blindly down the same paths of militant aggression as did the Russians and British will surely once again end in ever greater disasters, even more so when we have so clearly failed at cultural understanding and linguistic communication.

Dr. Thomas L. Markey, Tucson, Arizona, and

Dr. Jean-Claude Muller, Institut archéologique du Luxembourg