|

Toronto police have purchased four, long-range acoustic devices (LRAD) - often referred to as sound guns or sound cannons - for the upcoming June 26-27 summit, the Star has learned.

Purchased this month, the LRADs will become a permanent fixture in Toronto law enforcement, said police spokesperson Const. Wendy Drummond.

"They were purchased as part of the G20 budget process," Drummond said. "It's definitely going to be beneficial for us, not only in the G20 but in any future large gatherings."

Drummond stressed the devices will primarily be used by police as a "communication tool." The devices double as loudspeakers and can blast booming, directional messages or emergency notifications in 50 different languages; Drummond said Toronto police have used one of the devices already while executing a search warrant this month.

But critics say they are really non-lethal weapons and infringe upon protester rights.

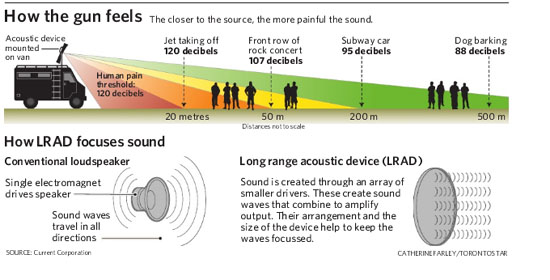

Originally designed for the U.S. Navy, LRADs can emit ear-blasting sounds so high in frequency they transcend normal thresholds of pain. While they are used everywhere from Iraq to the high seas for repelling pirates, LRADs are being increasingly employed as a crowd-control device and at last year's G20 summit in Pittsburgh, police used them on protesters before deploying tear gas and stun grenades.

The acoustical devices can also be pointed at specific targets, transmitting a "laser" of sound that is less aggravating for anyone standing outside its beam.

Of Toronto's newly-acquired LRADs, three are handheld devices that can broadcast noise heard from 600 metres away. Their volume can reach 135 decibels, which surpasses the pain threshold of 110 to 120.

The fourth device is a larger model that can be mounted on vehicles or marine vessels and can generate noise reaching 143 decibels, audible from as far as 1500 metres.

| Wired.com has a series of articles on the use and danger of LRAD. |

Drummond acknowledges LRADs can cause permanent hearing damage if used improperly but says Toronto police are developing guidelines for deployment. She said officers will also only use the device's "alert" function if crowds become riotous and will use the manufacturer's recommendation of firing short bursts, two to three seconds long.

"The piercing sound would make someone stop in their tracks for a moment," she said. "Your instinct would be to cover your ears. So rather than being violent, the tendency would be to stop the violence and protect your hearing."

While Drummond couldn't comment on how much the devices cost, they were purchased from B.C.-based Current Corporation, which sells LRADs at about $10,000 for the handheld models and about $25,000 for the larger ones, according to sales representative Don MacLeod.

MacLeod said his company trained police officers in Toronto on May 18, sharing deployment guidelines that include shooting a narrower beam of noise in small spaces, since the sounds can bounce off building surfaces or cars.

He criticized irresponsible users of the LRAD, including Pittsburgh's use of the device last year when officers ran a continuous aural assault as opposed to the short bursts, which Current Corp. recommends.

But MacLeod defends the LRAD as an extremely valuable communication tool, used for everything from evacuation notices and hostage negotiations to riot control.

But Queen's University professor David Murakami Wood, an expert in surveillance, criticizes neutralizing euphemisms like "communication tools". He says LRADs should be considered potential weapons and large international summits can often be used as testing grounds for new police technologies or techniques.

"They're being very disingenuous about what this is," he said. "It emits a sound that is in fact at frequency levels that can go way beyond what human beings can put up with in terms of pain and can be damaging."

For University of Toronto adjunct professor Peter Rosenthal, a lawyer who has participated in several trials involving Taser deployments, anything that can stun people or crowds should be considered dangerous.

"Tasers were introduced and said to be totally benign but have now generally been recognized as dangerous weapons," he said. "To start using experimental weapons on people is really outrageous in my view."Toronto Star