It is a common misconception, both in Haiti and abroad, that the country’s president holds executive power. In fact, his main power is to nominate the man or woman who does: the Prime Minister.

President Michel Martelly, after shunning consultations with the heads of Parliament’s two chambers (as the Constitution demands), saw his first two hard-line nominees – Daniel Gérard Rouzier and Bernard Gousse – rejected by the Parliament, which must ratify the candidate. This stand-off set off alarms in Washington, which saw the President it had shoe-horned into office still floundering without a government over three months after his May 14 inauguration.

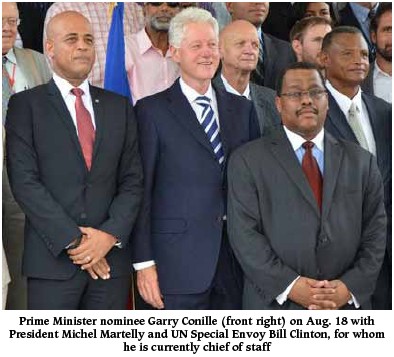

But now, following interventions by the U.S. Embassy (see accompanying article by Yves Pierre-Louis) and UN Special Envoy Bill Clinton with Martelly and Parliamentary leaders, a “compromise” nominee has emerged: Garry Conille, Clinton’s chief of staff in Haiti. Barring any surprises in the all-important background documents, Conille’s ratification is all but assured.

Garry Conille, 45, is the son of a Serge Conille, who was a government minister under the Duvalier dictatorship. He graduated from the Canado highschool in 1984 and trained as a doctor in Haiti’s State University Medical School. He then went on to earn a Master’s degree in Health Policy and Health Administration at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He then became a protégé of economist Jeffrey Sachs, who runs the liberal Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York. Sachs is often credited as the father of the “economic shock therapy” that was applied to formerly Communist countries in Eastern Europe after 1989. The “therapy” involved privatizing publicly owned industries, slashing state payrolls, dismantling trade, price and currency controls, in short, the same neoliberal “death plan” policies which Washington and Paris have sought to apply in Haiti over the past 25 years.

Sachs apparently had second-thoughts about the policies he spawned after their disastrous effects on working people and began to propose poverty alleviation, particularly through the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) which were put forth in a September 2000 United Nations summit of 191 nations. The eight goals, to be achieve by 2015, included targets to “reduce extreme poverty and hunger by half,” “achieve universal primary education,” and “reduce infant mortality by two-thirds and maternal mortality by three-fourths” and “stop the spread of pandemic diseases.” To report on how to achieve these goals, Sachs directed ten “Task Forces” of the UN’s Millennium Project, which according to its website included “researchers and scientists, policymakers, representatives of NGOs, UN agencies, the World Bank, IMF and the private sector.”

It is in this MDG work that Conille became one of Sachs’ collaborators (he is an adjunct research scientist at the Center for Global Health and Economic Development of Sachs’ Earth Institute). In May 2006, Conille co-authored with Sachs a set of recommendations to the incoming administration of President René Préval that called on the Haitian government to “establish a clear and consensual path out of poverty, that builds upon outreach to the business community,” the same “business community” which had responded to democratically-elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s proposed “path out of poverty” with a bloody 2004 coup. (In fairness, Sachs and, according to sources who have spoken to him, Conille opposed that coup.) They also called on Haiti “to reach agreements with the IMF and World Bank on a new three year development program,” the same international banks whose “development programs” have been underdeveloping Haiti for decades.

Principally, and not surprisingly, the prescription of Conille and Sachs was for “Haiti to establish a development strategy and implementation plan consistent with achieving the Millennium Development Goals.”

African economist Samir Amin submits the Millennium Development Goal strategy to a withering analysis in the March 2006 issue of Monthly Review. “A critical examination of the formulation of the goals as well as the definition of the means that would be required to implement them can only lead to the conclusion that the MDGs cannot be taken seriously,” Amin writes. “A litany of pious hopes commits no one. And when the expression of these pious hopes is accompanied by conditions that essentially eliminate the possibility of their becoming reality, the question must be asked: are not the authors of the document actually pursuing other priorities that have nothing to do with ‘poverty reduction’ and all the rest? In this case, should the exercise not be described as pure hypocrisy, as pulling the wool over the eyes of those who are being forced to accept the dictates of liberalism in the service of the quite particular and exclusive interests of dominant globalized capital?”

Amin takes special aim at MDG # 8: “Develop a global partnership for development.”

He responds: “The writers straightaway establish an equivalence between this ‘partnership’ and the principles of liberalism by declaring that the objective is to establish an open, multilateral commercial and financial system! The partnership thus becomes synonymous with submission to the demands of the imperialist powers.”

Writer Naomi Klein, the author of the best-selling book “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism” also points to the contradictions of Conille’s mentor in a 2007 interview with Oscar Reyes in “Red Pepper Magazine.”

“A lot of people are under the impression that Jeffrey Sachs has renounced his past as a shock therapist and is doing penance now,” Klein explained. “But if you read [Sachs’ book] ‘The End of Poverty’ more closely he continues to defend these policies, but simply says there should be a greater cushion for the people at the bottom.” In fact, “This is really just a charity model,” Klein concludes. “Let us be clear that we’re talking here about noblesse oblige, that’s all.”

So this is what Conille represents: the liberal wing of the U.S. bourgeoisie as represented by Sachs and Clinton.

When Dr. Paul Farmer, now acting as Clinton’s deputy UN Special Envoy, embarked on his new role in 2009, he had to put together a team. “Jeff Sachs helped me try to recruit Garry Conille, a Haitian physician schooled in the ways of the UN, to head the team,” Farmer writes in his just published book, “Haiti After the Earthquake.” “But Conille was otherwise occupied, the UN told us.” At that time, Conille was the UN Development Program’s Resident Representative in Niger. But then, two months ago, he became Clinton’s chief of staff with the title “Resident Coordinator of the UN System in Haiti.”

As Samir Amin points out in his MDG analysis: “The United States and its European and Japanese allies are now able to exert hegemony over a domesticated UN.” It appears likely that they will also be controlling a thoroughly domesticated Haitian prime minister.

Source: Haïti Liberté