Editor's Comment

The exemplary report below on the treatment of immigrant peoples was authored by Tamara Pearson*, a journalist who is based in Venezuela and writes for Venezuela Analysis. As an adopted son in Venezuela, I have experenced the truth of Tamara's report, having immigrated here as an older man from the U.S. in 2007. Since then I and my family have been blessed by the warm acceptance of the Venezuelan people and treated with great kindness by the Venezuelan government. The free quality health care (even when visiting multiple times from 2004-2007) and the fruits of a thriving economy from Venezuela's largess have exceeded any expectations I might have had. My acceptance here as a U.S. citizen is more profound when one considers how the United States treats Venezuelans and their government. When immigrants are being abused and rejected in the United States and other countries of great wealth, Venezuela stands out as a shining example of dignity, love and humanistic values. - Les Blough in Venezuela Krosbi Quintero, a Venezuelan, spent 60 days in a migrant prison in Spain, he told Clarin last year. Before that, he had been detained ten other times for not having identity documents. In prison he and other inmates were given Alprazolam, normally prescribed for panic attacks, so they wouldn’t “create problems”. Quintero said migrants were blamed for “stealing jobs”, and police hunted for undocumented migrants in the train stations, stepping the hunt up when Spain’s economic situation got worse. Quintero claimed the police focused on darker skinned people such as himself. While most first world and imperialist countries criminalise refugees and undocumented migrants, scapegoating them, promoting racism, and mistreating them, Venezuela welcomes migrants; and provides them with the same rights as Venezuelan citizens. The Chavez and Maduro governments have never blamed the millions of migrants here for any of the problems the country is facing; rather, migrants -documented or not- are welcomed and receive health care, education, and other benefits.

Every household “has at least one Colombian in it” – Venezuela’s migration history

Flor Alba Gomez Yepez migrated to Venezuela from Colombia nearly forty years ago, but only recently received citizenship. She described how the treatment of migrants has changed over time in Venezuela to Venezuelanalysis. Gomez said,

Venezuela has the third highest number of migrants in Latin America, according to El Carabobeno. A 2011 World Bank study also put Venezuela in second place in the region for number of refugees, though the line between migrants and refugees is sometimes hard to draw, as many Colombians flee a range of factors, from violence to political repression, to economic hardship. Venezuela also has more migrants than emigrants. A 2011 study by Ivan de la Vega for the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) estimated the number of Venezuelans living overseas to be 1.2 million, while the World Bank in 2010 only registered 521,620. Either way, the number is well below the number of foreigners living in Venezuela, with an estimated 4.5 million Colombians. Venezuelans who move to the US tend to be young, with 55.26% under the age of 34, according to the US Homeland Security Department. The UCV study claimed that most people migrating to the US do so because of the crime levels in Venezuela, though perhaps the Hollywood myth of the US lifestyle is to blame, as crime rights in the US are not much better than Venezuela, and Latinos, migrants, and African-Americans are most frequently the victims. Further, historically in Venezuela, as in most third world countries, those who are educated here as professionals often end up working overseas – for lack of employment opportunities, or seeking a higher wage. According to Carlos Lage, of the Cuban state council, by 1999 one million scientists and professionals educated in Latin America “at a cost of some 30 billion dollars moved to developed countries, and now we have to pay in order to benefit from their scientific contributions”. In the other direction, many Colombians migrate to Venezuela, or visit it in order to benefit from the free health care and higher education. Women crossing the border in order to give birth is very common. Gomez said,

Under the dictatorship of Marcos Perez Jimenez, until 1958, Venezuela had an open door policy, which was then revoked by the Punto Fijo government which followed. However, with the development of the oil industry from 1963, South Americans, especially Colombians, began to migrate to Venezuela. In the next few decades, others came here fleeing military dictatorships in Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia and Chile. As petroleum prices rose, investment and employment was concentrated in the main cities. Then, in the 1980s the prices dropped, and with IMF adjustment packages, unemployment increased, seeing more people emigrating out. In Venezuela all human beings have the same rights Under the Bolivarian government, migrants’ rights have significantly improved. “Foreigners in the territory of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela will have the same rights as nationals, without any limitations,” reads article 13 of the migration law, passed by the Chavez government in 2003. Further, in February 2004, Chavez issued Presidential Decree 2,823, which began a national campaign to pay what he called “Venezuela’s historical debt to migrants”. Foreigners residing in Venezuela without documents could legalise their stay and become “indefinite residents”. They had to obtain a certificate of legalisation and an ID card, and were then granted the resident visa for five years. A few people had bureaucratic problems though with the process and in 2009 the identification and migration office, SAIME, renewed the process, seeing many of those last people finally able to get their visa. That year, every Monday- the day assigned to the process-, hundreds of people were seen queuing up outside the various SAIME offices. Gomez said,

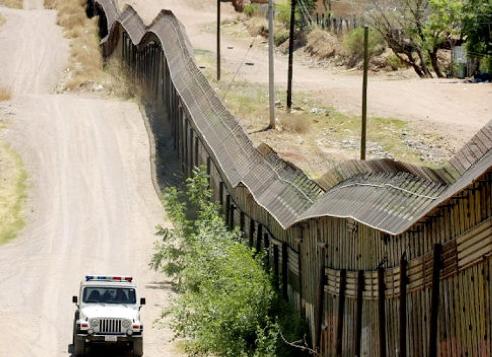

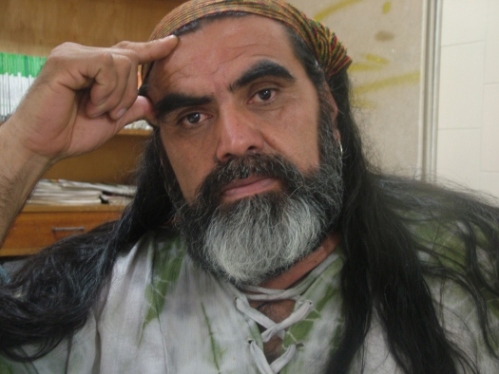

Now, having documentation and identification is a right, with the SAIME holding mobile cedulacion (ID card) stalls around the country, and police obliged to help children without documents to get identification. The few cases of undocumented or documented migrants being expelled from Venezuela over the last decade involve US diplomats allegedly conspiring against the government, people wanted with red alerts by Interpol, and in 2009, some people who were illegally extracting national resources, specifically gold and coltan. Venezuelanalysis also talked to Alejandro Carrizo, an Argentinean who came to Venezuela 4.5 years ago.

Carrizo explained,

Gomez argued that Colombians were better off in Venezuela, even without documents, than in Colombia, “There’s no freedom in Colombia and the people don’t count, aren’t taken into account in politics. The transnationals there...one in Putamayo, near the Pacific sea, destroyed the rivers for gold and didn’t ask the people there. There’s lots of exploitation, the wages are barely liveable, water, gas and electricity are all privatised, and education is almost totally privatised too, it’s very expensive. If a family has five children, two at the most will study. Here on the other hand, the gas is given away basically, studying is free, anyone who needs a medical exam, an x-ray, can just get one,” Gomez said. Even people migrating here from non Latin American countries tend to face few problems. Venezuelanalysis talked to Carlos Furtado, who works in a shop owned by Chinese people. As the owners spoke little Spanish, they preferred that I talk to Furtado. He explained,

Venezuela’s new police university, the UNES, which is focused on human rights, is currently running courses in migration, “to promote ethics in public attention and respect for human rights”. Forty SAIME workers started a course called the National Program for Training Civil Servants in the Area of Migration last September. Ruben Dario, a general director at the UNES, told press during the start of the course that Venezuela’s migration policy “is distinguished for being tolerant, without any kind of discrimination, solidarious, with complete respect for all migrant human rights, and for not criminalising migration”. The UN agency for refugees, Acnur, has also been able to work in Venezuela, saying it has trained around 10,000 people in ten years, among them military, police, civil servants, students, and NGOs attending to refugees. Acnur states that one of its aims in Venezuela is to strengthen refugees’ self sufficiency, and that while it started by handing out micro credits, now the state “has taken the reigns of this strategy of protection for many families who find it hard to earn a living”. Institutional bureaucracy is the main difficulty for migrants in Venezuela Despite the passing of the Law for the Simplification of Administration (2008), which declares that all bureaucratic processes should be free or affordable (they are) and as simple as possible, there are still serious bureaucratic problems here– of inconsistent requirements, unnecessary paperwork, insufficient information about requirements, and processing of requests can take too long. These problems affect all people here, but they disproportionately affect migrants, at times leaving them vulnerable. Though having legal documents like a visa is not a prerequisite for any social services such as health, subsidised food, political participation, education, and so on, visas help with leaving and returning to Venezuela. Not having a working visa can also leave people more susceptible to work place abuse, exploitation, and to having their worker rights, such as to pensioner savings, denied. The work law states that foreigners have the same rights as citizens, but employers can use the lack of a visa to intimidate workers anyway. Psychologically, people without visas may feel insecure, and they can also be more vulnerable to police harassment and extortion, though instances of such cases have drastically reduced over the last seven years. While obtaining a working visa, a business visa, or a family visa, and eventually residency, is much easier and affordable here than in Australia or the US, for example, the requirements for a working visa are still next to impossible; applicants have to obtain the work in Venezuela, have the ministry of labour approve the visa (one of the hardest things), then return to their country of birth to apply for the visa. Over the last seven years there have been serious improvements, with more SAIME offices around the country, processing time drastically reduced, and more consistent information about requirements. I remember first trying to get a legal visa in 2008. I had to travel to Caracas (16 hours in a bus). Then, literally dozens of people were swarming outside the SAIME building (then known as Onidex) trying to sell “stamps” that no one actually needed. Inside the building I tried to find out the requirements for a visa, and was sent from one office to another, to the point where I came full circle, still with no information. Now, there is a huge office in Merida. It takes just a morning to get a cedula (ID card), instead of a few weeks, and there are signs everywhere warning people that they do not have to pay for forms, and that stamps can only be obtained from certain registered shops. There is an information desk, and the national guard at SAIME are really helpful. Nevertheless, the process for becoming “documented” could be simplified much more. “I haven’t witnessed much discrimination, though yes, there are bureaucratic obstacles,” Carrizo said. “Some Colombians have been here for twenty years, and they [the government] should make it easier to processes all the paperwork much more quickly”. Latin America rejects borders “My family are indigenous, the Comechingones people, and I feel like I identify more with that. Our borders are different, we’re all brothers; Spain divided up the territory, such bureaucratic things aren’t part of our language. Mercosur is an advance towards a single and free territory, free of imperialism. We’d save a lot of paper,” Carrizo said. People from member countries of Mercosur don’t need a passport to visit other member countries as tourists. “Latin America is one country, you see that when you travel,” Gomez concluded. Leading and pushing regional blocs such as ALBA, Petrocaribe, and the CELAC, Venezuela has been taking concrete, though slow and small steps, towards a united Latin America based on cooperation between regions, and where borders either don’t exist, or are less prohibitive, and where no one is “illegal”. A CELAC statement coming out of a meeting for the protection of migrants held in June 2011 reaffirmed the member countries’ concerns “for the vulnerable situation of migrants and their families facing human rights violations and a lack of protection, something which urges states to increase their efforts ... to continue advancing in strengthening full economic and social development in our region, free of all the factors that force international migration, as that should be a free decision”. In this sense, the CELAC and Venezuela are setting an example for first world countries: showing that humane treatment of all migrants, documented or not, is easy and possible. Further, that the most important thing is to not force migration: to remove borders, to have cooperative trade policies (rather than the US’s trade policies which impoverish people in Mexico, Haiti, and so on), and to not support the invasion and destruction of other countries, such as Iraq, thereby creating the refugees that countries like Australia and the US refuse to look after. “How lovely that you and I are two immigrants talking about this,” Carrizo said as the interview concluded.

Source: Venezuela Analysis

(Note: Unless otherwise indicated, commentary, all photos, captions and light editing have been added to the original article by Axis of Logic) |