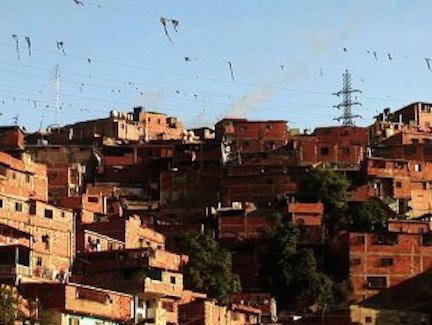

Before Hugo Chávez became president of Venezuela in 1999, the barrios of Caracas, built provisionally on the hills surrounding the capital, did not even appear on the city map. Officially they did not exist, so neither the city nor the state maintained their infrastructure. The poor inhabitants of these neighborhoods obtained water and electricity by tapping pipes and cables themselves. They lacked access to services such as garbage collection, health care and education altogether.

Today residents of the same barrios are organizing their communities through directly democratic assemblies known as communal councils — of which Venezuela has more than 40,000. Working families have come together to found community spaces and cooperative companies, coordinate social programs and renovate neighborhood houses, grounding their actions in principles of solidarity and collectivity. And their organizing has found government support, especially with the Law of Communal Councils, passed by Chávez in 2006, which has led to the formation of communes that can develop social projects on a larger scale and over the long term. You will not hear about the self-governing barrios in Western reports of protests spreading across Venezuela. According to the prevailing narrative, students throughout the country are protesting a dire economic situation and high crime rate, only to meet brutal repression from government forces. Yet the street violence that has captured the world’s attention has largely taken place in a few isolated areas — the affluent neighborhoods of cities like Caracas, Maracaibo, Valencia, San Cristóbal and Mérida — and not in the barrios where Venezuela’s poor and working classes live. Despite international media claims, the vast majority of Venezuela’s students are not protesting. Not even a third of all people arrested in connection with the demonstrations since early February are students, even though Venezuela has more than 2.6 million university students (up from roughly 700,00 in 1998), thanks to the tuition-free public university system that Chávez created. A look at recent arrests reveals that the “protest” leaders are really a mixture of drug traffickers, paramilitaries and private military contractors — in other words, the mercenaries typical of any CIA military destabilization operation. In Barinas, the southern border state with Colombia, two heavily armed barricade organizers were arrested, including Hugo Alberto Nuncira Soto, who has an Interpol arrest warrant for membership in Los Urabeños, a Colombian paramilitary involved in drug trafficking, smuggling, assassinations and massacres. In Caracas, the brothers Richard and Chamel Akl — who own a private military company, Akl Elite Corporation, and represent the Venezuelan branch of the private military contractor Risk Inc. — were arrested while driving an armored vehicle in possession of firearms, explosives and military equipment. Their car had been equipped with pipes to be activated from inside to disperse motor oil and nails on the streets, not to mention tear gas grenades, homemade bombs, pistols, gas masks, bulletproof vests, night-vision devices, gasoline tanks and knives. After Chávez’s death in March 2013, Venezuela’s opposition politicians saw an opportunity to win presidential elections, perhaps assuming that the public merely cared about Chávez’s famous charisma. However, the opposition’s leading candidate, Miranda state governor Henrique Capriles Radonski, lost to Chávez’s successor, Nicolás Maduro. Having been defeated in 18 of 19 elections since 1998, part of the opposition decided not to hold out hope for electoral victory any longer but instead to destabilize the country and violently oust its elected government. Most often the municipalities where the riots are taking place today are governed by anti-Chavista mayors who support them, either by participating in violent actions themselves or by ignoring the barricades defended with petrol bombs and firearms, instead of sending in municipal police, and by neglecting to collect trash so that the relatively well-off are stirred to revolt. What the wealthy in Venezuela are afraid of, and what mainstream media channels won’t show, is that a different world is possible — and Venezuela’s working classes are trying hard to build it. This is the real reason why the country is under attack. And make no mistake: this is a vicious attack on Venezuela, its infrastructure and its very sources of hope. On April 1, a group of rioters set the Ministry of Housing on fire with Molotov cocktails while 1,200 workers were inside the building. The fire was set close to the ministry’s nursery school, and 89 toddlers had to be evacuated by firemen. This lethal act is no anomaly. During the last several weeks, a university has been burned down, as have nurseries, subway stations, buses, medical centers, food distribution centers, tourist information sites and other civic spaces. In Mérida, the drinking-water reservoir was deliberately contaminated with fuel, and in Caracas, the nature reserve on the north side of the city was set on fire to destroy the power lines that supply the city with electricity. These attacks follow the same logic employed by the U.S.-backed Contras in Nicaragua in the 1980s: assail easy targets that symbolize the improvements to living conditions achieved by the government or organized communities and thereby spoil any hope that there is an alternative to the rule of capital. Yet there are ample reasons for such optimism. Through nationalizing its oil and gas reserves and investing most of its budget in social programs, Venezuela has become the only country in the world that achieved the UN Millennium Development Goals set for 2015, and it looks as if not many more countries will achieve them. The poverty rate in Venezuela has been more than halved since 1998, and extreme poverty has been cut by 70 percent. Today inequality is lower than anywhere else in Latin America and the Caribbean (not to mention the United States). The majority of people in Venezuela are far better off today than they were before Chávez was elected. There is no doubt that Venezuela is now going through a difficult economic situation; it has suffered high inflation and acute shortages of food and electricity during the last year. While mismanagement and corruption are problems, as the government itself has admitted, the shortages were caused mainly by speculation, smuggling and intentional reduction of production and hoarding by the private sector, just as before the U.S.-backed coup in Chile in 1973. Even so, during a visit to Caracas earlier this month, a representative of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) underlined the admirable efforts of the Venezuelan government to deepen the impact of social programs. In 2013 the FAO officially recognized Venezuela as one of 18 countries in the world to have achieved huge progress in reducing malnutrition, which dropped from a rate of 13.5 percent in 1990–92 to less than 5 percent in 2010–12. That’s why millions of Venezuelans continue to live their lives normally even if the effects of economic crisis always hit the poorest first. The protesters behaving violently and getting international media coverage identify with or are beholden to the classes least affected by the shortages and inflation. Most of Venezuela’s students are decidedly not protesting. But in truth, hardly anyone in Venezuela is protesting: they are waging war. Source URL |