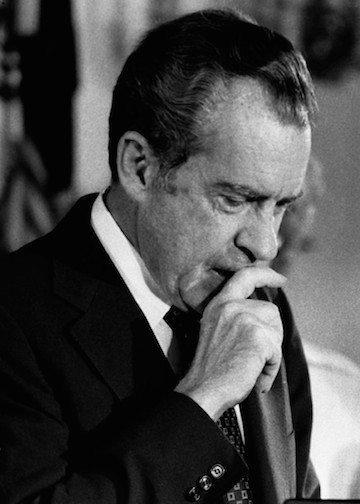

| Forty years ago, on August 9, Richard M. Nixon made unprecedented constitutional history when he resigned the presidency amid the disgrace and scandal of Watergate. He cannot escape that legacy — for he left an indelible record of his deeds in a treasure trove of tapes and papers that continue to fascinate us with revelations. Alas! Watergate is Nixon’s spot that will not out. The break-in, the ensuing revelation of what Nixon’s attorney general, John Mitchell, called the “White House Horrors,” the congressional and prosecutorial investigations that considered those travesties and Nixon’s eventual resignation laid bare unprecedented instances of presidential abuses of power and yes, criminality. Watergate was a major constitutional crisis; the promiscuous use of the suffix “gate” only trivializes it. Alexander Butterfield, who revealed the existence of the White House taping system, described Nixon as a man always conscious, if not obsessed, with history and his role in it. How ironic then that he left rich historical documentation, a self-inflicted wound as it were, that has so sullied his record and reputation. Yet Nixon endures. He stands as the commanding figure of American political life since the end of World War Two. His style, achievements and failures range over the political landscape and persist nearly two decades after his death. As a rising politician, as an opposition figure, as president and in his 20 years of “retirement,” Nixon greatly influenced his time. Today his impact is still apparent in so much of U.S. public life. He survives to praise or “kick around.” Either way, Nixon matters. Nixon’s history was not pretty. Beginning with his first campaign for Congress in 1946, Nixon honed the practice of wedge politics, which he has bequeathed to later politicians. His 1950 Senate campaign raised “Red-baiting” to an art form. When former General Dwight D. Eisenhower selected him as his running mate in 1952, Nixon deftly turned the controversy over his political funds to his advantage with the “Checkers” speech, inaugurating a new era of political television. As vice president, he stirred partisan conflict while Eisenhower seemed above the political fray. Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign against John F. Kennedy featured the first televised debates — and then the excruciating agony of Kennedy’s narrow victory. When Nixon ultimately won the White House in 1968, his presidency was marked by spectacular exercises of power, giving new impetus to the rise of the “Imperial Presidency.” Then came the riveting, still-resonant scandal of Watergate and his resignation, followed by Nixon’s final campaign for his historical legacy after he left the White House. His legacy is stunning. Nixon’s presidential record included a sweeping reorganization and consolidation of domestic policymaking in the executive branch. He transformed the 50-year-old Bureau of the Budget into the Office of Management and Budget, an agency of vast powers that can best be described as the gatekeeper of the presidency. In foreign policy, he and Henry A. Kissinger, who served as national security adviser before becoming secretary of state, reorganized the national security apparatus, centering foreign-policy decisions in the White House and circumventing traditional agencies. Nixon made respectable the idea of detente with the Soviet Union, though it aroused suspicion and fury from the GOP right wing. He made substantial progress toward nuclear arms control with the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks. In a particularly dramatic act, Nixon traveled to China in 1972 as both a Cold War tactic against the Soviet Union and to repair 20 years of diplomatic disarray. At the same time, however, Nixon spent four more years waging the futile war in Vietnam. He finally settled in 1973, on terms he could have had in 1969 — and without the 25,000 additional American deaths. The false claims of a “domino theory” and the subsequent lessons of Vietnam go ignored. Nixon and Kissinger also turned a blind eye to the massacres of Bengalis and of Iraqi Kurds, in deference to our allies in Pakistan and Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Nixon is credited with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, though the idea and legislation had long been nurtured in Congress. He did end the draft and sponsored the creation of an all-volunteer military. What had been a small professional army for most of U.S. history became a powerful institution, supported by increasing privatization of its duties and services. Nixon inaugurated revenue-sharing and block grants to states. But his supporters would rather forget the unsuccessful wage-and-price controls of his first term. They also cannot overlook his “closing of the gold window” in 1971, which marked the end of U.S. global financial dominance.

The Nixon administration had hoped to energize the U.S. economy and make American goods and services cheaper for export. The net result, however, expanded global financial activities and accelerated the decline of U.S. manufacturing — with a corresponding decline of high-paying, union jobs. With U.S. dollars no longer pegged to a fixed gold price, we printed paper money to buy ever-increasing goods and services from countries such as China and Saudi Arabia. These dollar-rich countries then invested in our debt at low interest rates. Nixon’s most enduring legacy, however, may be reordering the political and legal landscape. In 1968, Nixon pursued his “Southern strategy” as the path to the White House — and in the process transformed the South into a GOP political bastion. The “Solid South” had been moving away from its Democratic Party roots for several decades, increasingly uneasy with the party’s nurturing of a Northern urban base. In both his presidential runs, Nixon began to peel away Northern working-class voters, anticipating a later political development — blue-collar Reagan Democrats. Nixon’s victories laid the cornerstone of the “invisible bridge” to Ronald Reagan’s successful runs for the presidency, as Rick Perlstein has shown in a new book, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Nixon’s 1968 campaign provided a vivid preview of what was to come. He famously assaulted the U.S. Supreme Court for its alleged “softness” and the breakdown in law and order. Such criticism dovetailed with the attacks on the court since its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which declared segregation unconstitutional. Southern concerns about keeping African-Americans in “their place” drove massive white defections from the Democratic Party. Pursuing his Southern strategy, Nixon reshaped American politics. He and his advisers realized that the South –the Democratic Party’s “Solid South” — was ripe for a Republican takeover. Thus Nixon’s two-pronged strategy produced two enduring results for the emerging conservative movement. The defection of the South from the Democratic Party realigned U.S. politics, as Nixon attracted citizens of the New South as well as the Old South. The net result transformed the South, making it the dominant voice in the Republican Party. The other part of Nixon’s Southern strategy, reshaping the Supreme Court, began with his nomination of Warren Burger to succeed Chief Justice Earl Warren. Nixon told reporters that a philosophy of “strict construction” would guide his court nominations. “Strict construction” had been part of scholarly discourse about the Constitution. But Nixon made it a pliant phrase — grist for political exploitation and manipulation. When the Supreme Court, in 1962, struck down state-sponsored prayer in the public schools, Nixon first said he had “no intention of criticizing” the decision. Yet in the next breath he did, complaining that the court “had followed its usual pattern of interpreting the Constitution rigidly.” Though strict construction has proven to be more slogan than reality, it remains the most important codeword in American judicial politics. Virtually every judicial nominee since has been subjected in varying degrees to questions concerning his or her adherence to that doctrine. In addition, Nixon’s criticism of court decisions “played” well in the South, where lingering bitterness over the desegregation ruling prevailed. He also struck a chord among those who believed that Warren court opinions had favored criminals and lawbreakers. Nixon’s actions politicized the Supreme Court and established a language that prevails more than four decades later. Nixon nominated William Rehnquist to the Supreme Court when the Justice Department official was in his early 40s. Nixon presciently anticipated that Rehnquist would be instrumental in pressing the counter-reformation against the Warren court that the president so desired.

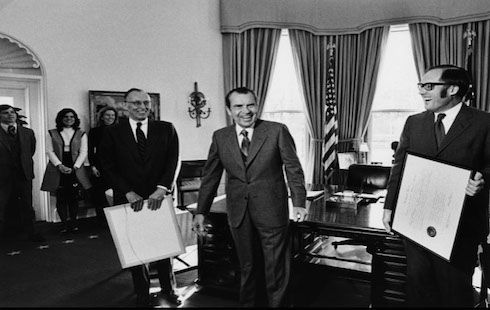

The Rehnquist appointment aligned the stars for Nixon. Rehnquist had first come to national prominence with a 1957 article attacking the Warren court’s “activism” and charging that the justices’ opinions were actually written by their clerks. He had served as a clerk himself, for Justice Robert Jackson, just four years earlier. Rehnquist’s article was in line with the criticism of Southern state supreme court judges when they assailed the high court for its desegregation decision. Rehnquist had also written a controversial 1952 memo to Jackson, supporting Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 decision that upheld segregation. This memo served Nixon well — for it signaled another volley, largely sub rosa, for the president’s Southern strategy. Rehnquist proved to be the realization of Nixon’s 1968 campaign wishes. He came to his position with a clear sense of purpose: determined to overturn and attack the constitutional landscape that had evolved during the 20th century. Rehnquist’s opinions on race, affirmative action, criminal law, business, reapportionment, federalism and the commerce clause substantially altered or reversed prevailing constitutional law. He began almost in isolation as, for example, with his 1973 dissent in Roe v. Wade. His dissent laid the groundwork for a steady retreat on abortion rights, whether in the political arena or in courts. Many justices appointed after 1980 were largely on the same page as Rehnquist. Nixon himself perhaps took particular pleasure as Rehnquist and his colleagues qualified or limited many of the momentous decisions of his hated rival, Warren — a former governor of California. After Rehnquist’s confirmation, he visited Nixon in the Oval Office on Dec. 10, 1971. The president was aglow over the appointment and used the occasion for one of his typical “pep talks.”

“I will give you one last bit of advice,” Nixon said, “because you’re going to be independent, naturally. And that is, don’t let the fact that you’re under heat change any of your views. . . . Just be as mean and rough as they said you are.”Nixon’s Southern strategy matured in 2013 when five Republican Supreme Court justices, largely in Nixon’s image, effectively nullified the heart of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, finding no justification for subjecting mostly Southern states to federal oversight. After nearly 50 years, and numerous updates by Congress, the majority found cause to overturn the law’s key enforcement procedures. Several Southern Republican attorneys general immediately announced that election laws, long questioned and delayed by the Justice Department, would now be implemented. The Supreme Court, once reviled in the South, now became the handmaiden for the South’s half-century struggle, led by a white establishment determined to preserve its power. Nixon matters. Source URL |