| The New Atheism Hoax: New Book Exposes the Deceptions of Dawkins, Dennett, Harris, and Hitchens In The New Atheism Hoax (www.pipr.co.uk/ebooks), I go through every post-WWII geopolitical claim made by the New Atheists and demonstrate how, in case after case, they take their own sources out of context and cherry-pick findings to suit their arguments. Let’s look at some examples: THE END OF FAITH In The End of Faith (2006 (2nd), Free Press), Sam Harris has much to say about terrorism and suicide bombing, arguing that only faith can drive people to such madness. Harris writes that researcher Scott Atran cites a Pakistani relief worker who interviewed nearly 250 aspiring Palestinian suicide bombers and their recruiters and concluded, “None were uneducated, desperately poor, simple-minded or depressed. . . . [Harris’s ellipsis.] They all seemed to be entirely normal members of their families.” He also cites a 2001 poll conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research indicating “that Palestinian adults with 12 years or more of education are far more likely to support bomb attacks than those who cannot read” (pp. 133, 253n27).

So, as poverty is not a factor, that can only mean religion is the cause. Harris’s source is Scott Atran, ‘Opinion: Who Wants to Be a Martyr?’, New York Times, 5 May, 2003. Here’s what Harris leaves out. Atran writes that terrorist agents ‘choose recruits who are intelligent, psychologically balanced and socially poised. Candidates who mostly want virgins in paradise or money for their families are weeded out’. Ergo, Harris’s own source says that suicide bombing is a military tactic and that the bombers are not motivated by religion. Religion is used as a bonding ritual and an assurance that the individual will go through with the mission, Atran argues, but is not the underlying cause.

Or let’s take Harris on Iraq. Furthering his case that Muslim populations need a benevolent if strict patriarch to steer them on the road to civilization and rationality, Harris writes: It would be impossible to do justice to the richness of the Muslim imagination in the context of this book. To take only one preposterous example: it seems that many Iraqis believe that the widespread looting that occurred after the fall of Saddam’s regime was orchestrated by Americans and Israelis, as part of a Zionist plot. The attacks upon American soldiers were carried out by CIA agents “as part of a covert operation to justify prolonging the U.S. military occupation” Wow! (p. 254n31).What Anderson actually wrote is that a single Iraqi, Dr. Butti, made the allegations. Anderson writes: Butti … was full of conspiracy theories concerning the American occupation. He spoke about a widespread belief in a Zionist plot to annex Iraq, and about how the Americans seemed to be going along with this, and also about how they had orchestrated the looting of Baghdad presumably as part of the plot. (Anderson, op cit., pp. 53-4).[1]In addition, Harris omits the fact that Anderson documented conspiracy theories perpetrated by the US invaders. Anderson writes: ‘I had noticed that many Americans in Iraq had started to make references to Al Qaeda terrorists when they talked about the attacks on U.S. soldiers, although there seemed to be no evidence for the claims’ (p. 46). To quote Harris: ‘Wow!’ More important, however, is Harris’s reduction of Anderson’s article, which goes some way to describing the misery of many of the Iraqis he met, to a critique of the population’s alleged belief in conspiracies about the people occupying them.

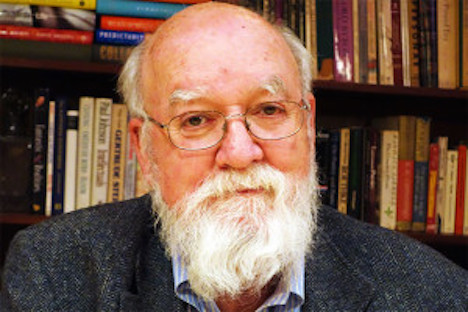

BREAKING THE SPELL In Breaking The Spell (2007, Penguin), Daniel C. Dennett also suppresses evidence in favour of supporting the State. Like Harris, he argues that religion is the main motivating factor pushing many to suicide terrorism. Dennett quotes the political scientist and Fulbright Scholar, Jessica Stern:

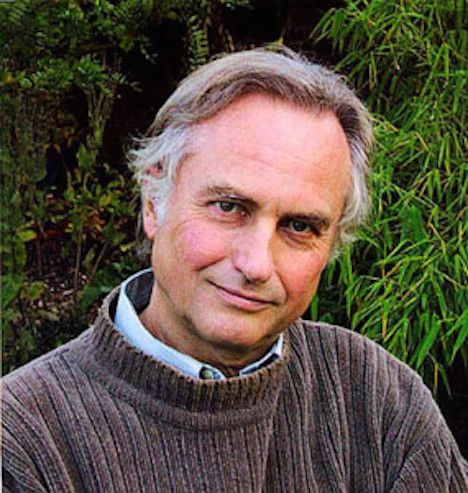

I have come to see terrorism as a kind of virus, which spreads as a result of risk factors at various levels: global, interstate, national, and personal. But identifying these factors precisely is difficult. The same variables (political, religious, social, or all of the above) that seem to have caused one person to become a terrorist might cause another to become a saint. [2] Dennett omits Stern’s painful account of the conditions that motivate some Palestinians to kill themselves and murder others in the process. Stern, a hawk who believes that Israel’s occupation is legal, writes (and this is what Dennett leaves out): Israel declared all water resources state-owned following the 1967 war, severely restricting water access to the now 1.2 million Palestinians of the Gaza Strip, while simultaneously subsidizing and encouraging water consumption for six thousand Israeli settlers living in the Gaza Strip. The land appropriated for the settlements was also superior in terms of groundwater quality and quantity, a source of much anger amongst Gazan Palestinians to this very day. [3]Ironically, Dennett writes about addressing Muslim grievances. His own source (Stern) does so, but Dennett chooses to ignore the findings. Stern writes that in 2002, a Zogby poll revealed that [Muslim] youth, in particular, were far more sympathetic to the United States [before the invasion of Iraq,] when the main complaint was U.S. policy in regard to Israel. In March 2003, there was widespread perception in the Islamic world that U.S. government policies were anti-Muslim across the board. John Zogby explains, “We have lost a lot of good will for a long time … The problem is that someone will reach [youths] and organize them and that does not bode well for the United States.” (ibid., p. 356n14.)In protecting what he praises as a democratic state, Dennett absolves the US of culpability. THE GOD DELUSION Writing about the ‘pusillanimous reluctance’ of media to frame stories as battles between religious groups, Richard Dawkins in The God Delusion (2006, Black Swan) provides a single example: a newspaper article in the Independent about Iraq. ‘Iraq, as a consequence of the Anglo-American invasion of 2003, degenerated into sectarian civil war between Sunni and Shia Muslims’, writes Dawkins (p. 43). He adds: Clearly a religious conflict – yet in the Independent of 20 May 2006[,] the front page headline and first leading article both described it as ‘ethnic cleansing’ … [But w]hat we are seeing in Iraq is ‘religious cleansing’. (p. 43).

This is all the information he provides. His source turns out to be an article by Patrick Cockburn, one of the world’s leading Middle East correspondents. Cockburn’s article is titled, ‘Iraq is disintegrating as ethnic cleansing takes hold’. Dawkins does not actually quote from Cockburn’s article, he merely references it. Cockburn’s article in fact goes into detail about why the violence was indeed ethnic not religious cleansing: it discusses Kurds and Arabs (both ethnic groups), yet Dawkins implies it discusses only Sunni and Shia Muslims. Cockburn writes: “Be gone by evening prayers or we will kill you,” warned one of four men who called at the house of Leila Mohammed … Her husband, Ahmed, who traded fruit in the local market, said: “They threatened the Kurds and the Shia and told them to get out.[”] … I thought it was too dangerous to go beyond the town into the Arab part of Diyala province. But, as I had hoped, it was possible to talk to Kurds who had sought refuge in Khanaqin over the past month. (Emphases added).

GOD IS NOT GREAT In God Is Not Great (2007, Atlantic), the late Professor Christopher Hitchens hints that the Rwanda genocide was in part an ethnic-tribal dispute and then claims that religious differences between the Hutu and Tutsi, stoked by priests, escalated tensions into genocide. To advance this theory, he writes: in 1992, when at a given signal[,] the racist militias of “Hutu Power,” incited by state and church, fell upon their Tutsi neighbors and slaughtered them en masse. This was no atavistic spasm of bloodletting but a coldly rehearsed African version of the Final Solution, which had been in preparation for some time. The early warning of it came in 1987 when a Catholic visionary with the deceptively folksy name of Little Pebbles began to boast of hearing voices and seeing visions, these deriving from the Virgin Mary. The said voices and visions were distressingly bloody, predicting massacre and apocalypse but also—as if in compensation— the return of Jesus Christ on Easter Sunday, 1992. Apparitions of Mary on a hilltop named Kibeho were investigated by the Catholic Church and announced to be reliable. The wife of the Rwandan president, Agathe Habyarimana, was specially entranced by these visions and maintained a close relationship with the bishop of Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city. This man, Monsignor Vincent Nsengiyumva, was also a central-committee member of President [Juvenal] Habyarimana’s single ruling party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development, or NRMD. This party, together with other organs of state, was fond of rounding up any women of whom it disapproved as “prostitutes” and of encouraging Catholic activists to trash any stores that sold contraceptives. Over time, the word spread that prophecy would be fulfilled and that the “cockroaches”—the Tutsi minority— would soon get what was coming to them.

Hitchens omits Gourevitch’s history of recent Hutu/Tutsi conflict. Gourevitch writes: Uganda rebels, led by Yoweri Museveni, who were fighting against Idi Amin from bases in Tanzania … [In 1979,] Amin fled into exile, and [Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) leader Paul] Kagame joined … the Museveni faction of the new Ugandan army. In 1981, when the former dictator Milton Obote again seized power in Uganda, Museveni returned to the bush to fight more. His army consisted of twenty-seven men, including … Kagame.‘Little Pebbles’ and his prophesy had minor significance, Gourevitch writes: ‘I can’t say that Habyarimana ever read this forecast, only that it found its way into his household, and that it was close in spirit to views that fascinated his powerful wife’.[6] Neither Hitchens nor Gourevitch mention the complicity of Belgium, Britain, France, and the US in the genocide.

CONCLUSION The New Atheism Hoax goes into more detail and debunks every post-WWII geopolitical claim made by the New Atheists. It is available at www.pipr.co.uk/ebooks Notes:

Source URL |