Doing time creates a demented darkness of my own imagination… — Leonard Peltier, Prison Writings: My Life Is My Sundance Leonard Peltier could not be present at the exhibition of his artwork at the second Indigenous Fine Arts Market (IFAM) in Santa Fe, NM, held on August 20-22, because he’s been incarcerated in the U.S. federal penitentiary system for the last 40 years. He’s currently in Coleman (Florida), a known “gang prison,” a brutal and violent place subject to frequent lockdowns lasting not uncommonly for as long as a month. Maybe next year? While the primary focus of this article is not the case for clemency, the reality is that presidential intervention is his only remaining avenue to freedom. Barring the appearance of some staggering new piece of evidence, all appeals for a new trial have been thoroughly exhausted. The feeling among his inner circle is that a new president, whoever it may be, is unlikely to risk involvement; but a lame duck president just might quack Peltier’s way. The mere fact that this show has almost miraculously manifested whets the appetite for hopefulness. A few points by way of context: There has been an established Indian art market in Santa Fe for the last 93 years, operated by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, or SWAIA. They claim to bring in $100,000,000 of revenues to Santa Fe, and it is the oldest and largest Indian art market in the nation. The word venerable is often invoked. But two years ago three of their Native American staff resigned and formed a cheaper, more inclusive, more varied, less hierarchical and more participatory, alternative Indigenous arts market — IFAM; they held their first market in 2014, simultaneously with SWAIA’s (much to SWAIA’s consternation). Afterwards, the editorial board of the Santa Fe New Mexican weighed in with a Solomonic “Our View” column accepting the renegade market. How could they not? By all metrics it had been a raging success. All to say, these issues of self-determination — who gets to show, what they are permitted to show, booth affordability — are very much alive in the present moment, and the example of IFAM itself as a successful challenge to stasis, complacency, even rot (venerable rot, naturally) is empowering. Second, (and also empowering) Melanie K. Yazzie of the Diné Nation, co-founder of The Red Nation and American Studies PhD candidate at the University of New Mexico has written a brilliant, if scathing, takedown of some of the major museums in New Mexico, calling them out, exhibit by exhibit, for their less than honest portrayals of colonial violence against Native peoples. It’s called “A Native Critique of New Mexico History,” and critique is putting it mildly: she makes the hair on the back of your neck stand up. She argues that in the interest of pandering to tourism, the history museums are guilty of erasing the truth about the barbaric consequences to Native peoples from colonization. …the tropes of benign enchantment and tri-cultural harmony cater to a specific audience whose primary interest is learning about “something new and different” through associative markers like the American Dream, historical objectivity and multiculturalism. In the end, this approach seems to be a veiled attempt, routed through the narrative of tri-cultural harmony, to testify to the promise of progress and prosperity that whiteness and U.S. nationalism has brought to New Mexico. It also evokes the privileged position that Whites occupy in New Mexico’s economic juggernaut comprised of tourism (here I’m thinking about the railroad and Fred Harvey exhibit), resource extraction and exploitation, militarism (lots of guns, rifles and uniforms on display), and nuclearism.Colonization, Yazzie makes clear, is not relegated to the vicious exploits of Olde Tyme Spanish conquerors of yore, but is ongoing with a vengeance. Today, the colonial project exceeds practices of native enslavement and cultural destitution. It now includes catastrophically inadequate health care and other public health services, rampant poverty, criminalization and incarceration, disease and contamination from resource plunder and the rape of sacred lands, substance abuse, militarization and police violence, gender and sexual violence, homelessness, child and elder violence, and the general disposability and dehumanization of Native peoples.

To Yazzie’s “criminalization and incarceration” point, the Peltier Art Committee has issued this terribly relevant statement: Leonard Peltier is the longest held Native American political prisoner in the U.S. He was wrongfully convicted in the 1975 killing of two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Leonard was at Pine Ridge at the request of the traditional elders who witnessed the brutal murders of over sixty Native people in what is termed the “reign of terror.” To date, no one has been charged or brought to trial [for those 60 murders] and yet he has served over 40 years for standing between the line of fire and the Keepers of our Sacred Ways on the very soil that was witness to the massacre at Wounded Knee. The trial for Leonard consisted of numerous documented constitutional violations, intimidation and coercion of government witnesses, falsifying of information, and manufactured evidence. Although the prosecutor admits “we don’t know who killed the agents,” and Mr. Peltier was denied the right to present a defense, he remains in a super-max penitentiary…The Peltier capture and incarceration story is an important through line in the ongoing narrative of colonization of Native peoples. As much as one might desire to assign him dual hats — a jaunty beret for artist, a feathered warbonnet for AIM freedom fighter — the identities are merged, and not readily separable; donning and doffing haberdashery is a privilege a man in Leonard Peltier’s position does not possess. He has but one vulnerable hatless, head, and it’s been on the chopping block for a very long time.

I’m skipping ahead, but in the presence of the canvasses themselves one feels every brush stroke as a droplet of water that might cumulatively erode the walls and rust the bars that isolate him from most everything and everyone he holds dear. There’s nothing casual or recreational or hobbyistic about his paintings: whatever else they are — aesthetically, symbolically, or discursively — stroke by measured stroke, each one is a quiet demand for personal liberation. More and more, as people become aware of his body of work, Peltier is being taken seriously as a fine artist. James Rutherford of Chiaroscuro Gallery on Canyon Road, one of the important Santa Fe galleries exhibiting extraordinary works of Native American arts, showed Peltier’s oils at his former gallery — Copeland Rutherford — in the nineties. Though there’s no catalog of that show, (“The show happened well before the days of print on demand,” Rutherford reminded me) somewhere in his dusty archives there’s a snapshot of Rutherford posed with Hollywood actor Kris Kristofferson wearing a Free Peltier tee-shirt. It’s important to note, that although self-taught and an Outsider artist (no one would dispute that), Leonard Peltier has not been relegated to the often marginalized realm of Prison Art, which is only just: his artmaking preceded his political martyrdom. For Peltier, making art isn’t a prison pastime, something diverting to do while whiling away the years, or decades, or heaven forbid, half-centuries; but something far deeper. From his 1992 book Prison Writings: My Life is My Sundance: …as a little kid I’d once found a pocketknife in the trash, sharpened it up and started carving pieces of wood — little statuettes of buffaloes and dogs and birds…I learned to draw before I could read or write, and it was a kind of way to communicate for me. I was an A student in school art classes. I was especially impressed by one particular man I met on the Fort Totten Reservation who went around to people’s homes, painting pictures in exchange for his room and board. I was fascinated by his lifestyle and the way he communicated with people through his art. That, I decided, would be the most wonderful life, just traveling around and earning your living as an artist.Dreamer that I was, I wrote to an art school I’d heard of in Santa Fe and tried to get a scholarship. They said no, but try again. I tried again a while later. Same reply: no. I often wonder what my life would have been like if I’d just gotten that scholarship.”

Candice Hopkins, citizen of the Carcross/Taqish First Nation and Curator of IAIA’s Museum of Contemporary Indigenous Arts (MOCNA) is excited to see Leonard Peltier’s show if she can possibly get there. Though the distance between Santa Fe’s historic plaza where her institution is located and the Railyard Park where IFAM is situated is very much walkable, market week is crunch time for Native Arts professionals; intense 16-hour workdays are not unusual in the ramp-up to market week. And while she was gracious in the extreme to interrupt her ferociously busy day supervising the hanging of four new exhibits to prioritize thinking and talking about Leonard Peltier’s art, she was not merely so. In Hopkins’ barn-burner of a chapter about the 2010 Postcommodity show “If History Moves at the Speed of its Weapons, Then the Shape of the Arrow is Changing,” she made explicit her understanding of Power’s need to manufacture Indian terrorists. …we are reminded of the roots of terrorism as something that does not emerge fully formed from some unknowable impulse but is often an unintended result of the transformation of imperialism into new forms of domination. “History also teaches us,” writes Said, “that domination breeds resistance, and that the violence inherent in the imperial contest — for its occasional profit or pleasure — is an impoverishment for both sides.” Central to this, and to the historical amnesia that continues to plague the United States regarding its relationship to Indigenous people, is the need to continually generate a “distant and mostly unknown enemy” always formed relative to national narrations. Further complicating matters is the increased labeling of Indigenous people as potential terrorists by the United States and Canada. But what is shared by those who, left with little choice, resort to more extreme forms of resistance, is a desire to disengage market forces in their various forms — whether they be resource extraction on traditional lands or the granting of rebuilding efforts in Iraq to U.S.-owned corporations. Understood simply, these market forces are symptomatic of the transformation from imperialism into empire and the machine of hyper-capitalism that fuels the insatiable appetite of the latter.

Hopkins’ first encounter with Peltier as artist was at the 2012 Whitney Biennial in Manhattan when artist Joanna Malinowska hung one of his canvasses in her own installation as a commentary on the lack of inclusion of Native American artists in the Whitney’s permanent collection of American Art. “Hers was a complicated position,” Hopkins said. “Why did she, an Eastern-European, have to be the one to initiate the conversation?” There are hundreds of Native American artists who should be represented in their collection. There was this sense that yes, of course, Peltier has a huge following, but perhaps selecting him was something of a naive gesture. There’s a bigger hole to fill, Leonard Peltier can’t fill it alone… Peltier’s work was a revelation for me. His painting was beautiful; its subject was not incarceration, but a picture of the world, a gesture toward the importance of land and animals. I stood before it filled with this belief he was putting forward of beauty, hope, optimism. I thought of this term I’ve written about–“the sovereign imagination”–and all that could imply for Leonard Peltier, his body incarcerated, but his mind free. Gerald Vizenor’s term “survivance” is perhaps another way to understand Peltier’s work: creating art as “a renunciation of dominance, tragedy, victimry.”“It changed my perception of him, knowing that he made art,” says Hopkins. One can’t help thinking about his being incarcerated and Time, how much importance the drawings and paintings might take on as another way of expressing himself. Though Peltier is always remembered at events, in fliers, rallies and direct actions, this show will be an introduction for a lot of people, to see this side of him. And how welcome it would be, of course, to have Leonard Peltier embraced as part of the Indigenous Arts community.

John Torres Nez, president of IFAM, stood tall against the few but vociferous voices that wanted Peltier to stay out of sight and out of mind. John received what he characterized as “harsh emails and unpleasant phone calls” (others told me they were death threats) from those objecting to federal prisoner No. 89637-132 being allowed in the show. True, the rules would have to be bent to accommodate him, in the ordinary course the artist’s presence is required — that is a grievance that was actually put forward by the naysayers. But Chauncey Peltier, Leonard’s eldest son, was willing to drive the 1200 miles from Portland, Oregon, straight through the night if need be, to represent his father. Still, several Native artists dropped out of the exhibition altogether, accusing Nez of “politicizing the show.” John’s courage is constitutive of his aspirations for IFAM, and as a consequence he’s created a felicitous moment which could mark a pivotal reversal of fortune for Leonard Peltier. John put it this way: “It’s what I’ve always done, it’s who I am. I come from an activist family, we’ve always been involved. Leonard Peltier’s name has always been remembered; I write letters asking for mercy on his behalf. I’m actively involved with incarcerated men through Hope-Howse, an inmates group. A lot of them are there for stupid mistakes,” he explained. “I offer them art as a possibility for creative expression, as a therapeutic mode, and as a potential profession when they exit the prison system.” It’s a serious hope to proffer, but not fantastical. There are artists who make their entire year’s earnings during Indian Market. It can be a frenzy. Rich ladies from Texas pay peons to sleep in front of artists’ booths so that when the market opens they’re first in line to buy everything of their choosing. IFAM too could become such a conduit for turning promising hopes into delightful realities. Why not? As I strolled the lanes of the market, people were shopping with a pleasurable aplomb; happily pulling their one-of-a-kind purchases out of their wrappings to show their friends the lucky treasures and to receive heartfelt congratulations on their charming finds. “Last March,” he continued, “we received Leonard Peltier’s application; the timing was exquisite. When I reviewed it, I did a double-take; I’d never seen his work.” The Peltier application went through the same juried process the other 500 applicants did. The new market received twice the number of submissions as it had in its inaugural year. For Torres Nez the numbers serve as proof that IFAM, as he has helped to conceptualize it in collaboration with Tailinh Agoyo, Paula Rivera, and others, is filling a genuine need. A need he defines as “ownership.” “Before IFAM there was a stranglehold on the Native Arts world — with the same gallery owners and trading-posts setting the prices and the payouts, the economics were skewed against the artists. As time went by it became a system of exploitation, with all that that implies. IFAM is cheaper, fairer, and even more important is how the show is run, who gets to participate.” The show is juried by a panel of art professionals, but it’s not “blind.” According to Torres Nez, “Blind is a joke. Anyone really immersed in the Native arts scene is going to recognize whose work is who’s.” The judges settled on 350 artists, a hundred more than last year. “350 is still a manageable size, the show doesn’t lose its intimacy. “When I saw Peltier’s work, I was impressed. There’s some really nice pieces in there, some really fine work. Of course he’s self-taught, which made it all the more impressive.”

Peter Clark, co-director of the Peltier Defense Committee explained that Leonard buys his paints and other art supplies through his prison commissary account, and not surprisingly there are certain constraints. (As Leonard himself told me when we spoke by telephone two days later: “We’re very limited by what we’re able to do in prison, in what we can do.”) The commissary account is fueled largely by donations and 20% of the proceeds of the sale of his artworks. From time to time art supplies are donated prisoner-to-prisoner if someone’s being transferred, or released. Peter informed me that Leonard himself has left his art supplies behind for another prisoner when he’s been moved around — Leavenworth, Lewisberg, Springfield, others too. (The details of his various transfers are recounted on the website Who Is Leonard Peltier?). “The Committee is tasked with making sure Leonard has sufficient funds to fund his artmaking,” Peter explained. “Another important source is the Stanford California PowWow. They have a Leonard Peltier table every year and collect donations; last year they collected $1,000. Not often, but sometimes, the account will dwindle to zero and he’ll ask us to send some money. He’s past retirement age, he’ll be 71 years old on September 12th, so he doesn’t work for money inside the prison.” Albuquerque is now the capitol of all things Peltier. In May the International Free Leonard Committee opened an office in the Peace and Justice Center under the umbrella of the Indigenous Rights Center. “We wanted to corral all the efforts being done in Leonard’s name in one place, efforts such as the donations of holiday gifts to the children of Pine Ridge and Turtle Mountain. In addition, we hold public events and are involved in supporting the activities of The Red Nation and UnOccupy Albuqerque on behalf of Indigenous peoples.” As Peter and I were talking, a graphite drawing of a majestic elk was sold for $500, the first “big” sale, and we were all elated. That one transaction went a long way toward defraying expenses, and it was only Day One of market. Clark travels to Florida along with Native prisoner rights activist Lenny Foster, Leonard’s spiritual adviser, every three months, or so. “The meetings are great,” Peter said, “because the communication is so much more direct than by email where you’re always reclarifying. We’re more relaxed. Apart from our main purpose, we talk mechanics, music, current events in the outside world. It was fun trying to explain Facebook to him. Try explaining that to someone who’s never seen it!” Peter is trying to make the case for clemency irresistible to Obama. “After forty years, the sentences are served. At the time he was sentenced the standard was 15 years for a life sentence. Leonard got two life sentences, and another seven for the attempted escape in California, and he’s already served more than that. “We have a mounting pile of documentation from an impressive list of persons and organizations in support of Leonard including the National Congress of American Indians and the United Nations. The president would be healing an open wound in Indian Country on a par with the Sand Creek Massacre and returning the Black Hills. Obama is our last chance, in fact, we feel he’s our only hope.” Longtime American Indian Movement (AIM) member Bobby Valdez from Laguna Pueblo is collecting signatures for the clemency petition, and he’s come a hundred miles to do it. He thinks of Leonard Peltier every single day. “In my prayers. I ask the Creator to help him through another day, to keep him healthy until his release. I think of him every morning when I greet the sun and light the sage, when I bless the cornmeal mixed with stones of coral or turquoise.” Together we name the deprivations of incarceration — family, the natural world, the dignity of privacy, favorite foods. “I would miss fry bread” Bobby admits, “and backbone red chili stew.” And lovemaking? Bobby and I talk about the fact that Leonard has six children with five different women, and what a lusty young man he must have been back in the day. “As for lovemaking, I’m sure he has some kind of love life, if only the vision of the partner he’s going to have when he gets out. As spiritual as Leonard is it’s going to come for him; there’ll be someone waiting for him. For me he’s a leader, an artistic individual, a fighter, and we’re not going to give up.” Sam Gardipe of the Pawnee Nation, another member of AIM, said, “What happened to Leonard Peltier could have happened to any one of us, fighting for freedom, putting yourself out there at risk of being incarcerated for something you didn’t do. Being a warrior is having a heart for our people, and taking care of the weak. That’s what Leonard was doing up at Jumping Bull when the FBI agents lost their lives. And now he’s sacrificing for our people; he’s been doing it a long time, and that is the ultimate sign of a warrior. “I pray he’ll get out and I’m sure he will. When you pray you believe in your prayer. I know it’ll happen by the power of praying. It means more when Natives practice the traditional ways.”

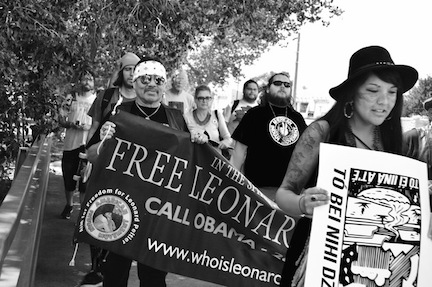

Fifty on his next birthday, Chauncey co-directs the Defense Committee with Peter Clark, plus he’s taken on the responsibility for the artwork. “When I took over the art, I didn’t take over any resources to go along with it; I had to reach out for everything. I had to go out to Wisconsin and North Dakota and pick it all up. This art business can be very time consuming; I get calls at work, I always got stuff I’ve got to handle. I still got to work too, I’m not trying to get anything out of my dad.” He sees his primary function as “keeping everyone honest and getting them all to cooperate. To help dad get out.” I ask him if he ever fantasizes about busting his dad out of prison. Nooooo, but I’d like to see him come home. I always wondered what it would have been like to grow up together. We like a lot of the same things. Everyone says we’re exactly the same. He’s into masonry and mechanics, and so am I. Makes me wonder if we would’ve bumped heads.I ask Chauncey if any other Native men ever came into his life, to act as a surrogate father. No. I remember one time when I was young, I called the Defense Committee. They didn’t help at all, they didn’t even know who I was. They told me not to call back.Chauncey drove down from Oregon with two young Mexican-American compadres — Wallace Javier Perez, the son of a friend, and Jordan Oliva. While Chauncey was manning the booth they were busy promoting the show and connecting with activists who for months have been occupying the Oak Flats campsite in Arizona in protest of a planned copper mining on a sacred site, a Sen. John McCain fix. A march around the plaza and through Indian Market was being planned for noon the next day and they hoped to carry the Leonard Peltier banner. “I got into activism progressively,” Wallace said. “I was at a national Rainbow Gathering in Washington State, and there was this guy with a blanket who had all this information laid out — about 9/11, waterboarding, the Black Hills — stuff that’s controversial, that you can come up missing just for thinking about. Here in Santa Fe we’re approaching random people at Walmart asking them if they know about Leonard Peltier; it’s overwhelming how much support there is.” “If Leonard Peltier was here right now,” Jordan said, “I’d tell him thank you for the hope, thank you for standing up for other things too, like against the Keystone pipeline. Thank you for hanging in there, I’m glad you’re out. I’m glad America woke up, that you sent a message to activists all over the world. Not just to Native Americans. But for the human race, all around the world. I hope you enjoy the rest of your life, spending time with your family. And I would tell him that our protest action tomorrow is: Save Oak Flats, Free Leonard Peltier.” Before the march while the group’s assembling I speak with Laura Medina, 28, of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottowa and Chippewa, who is an Apache Stronghold Occupier. “I’m here to support Lynette Houzous (the action’s organizer) and to help bridge the movements, show awareness and protect the sacredness. I am here because there is a resurgence of people who are passionate; I’m here with my dad, my brother and my boyfriend. The crimes against the Animas River bring light to what’s happening in all these mines on our lands — uranium, coal, copper. In Oak Flats, Arizona, the copper miners want to blast a mile-wide crater a thousand feet deep. Everything is urgent, but what requires attention right now is Oak Flats. Our tribal government leader is fighting for the land. This is really unusual because they still have to make an oath to the U.S., and will never really be sovereign. We don’t want to emulate normal capitalist business practices. What if we thought of economic development in our traditional spiritual terms, and we established bartering and trading systems instead of systems destined to lead to economic exploitation? There’s a big push for tourism on our lands as a pathway to resource development. But the schemes are in the hands of the tribal government that answers to the U.S government.

There was no chance to speak with Lynette at the march other than a quick hello, but she emailed me this message: SaveOakFlat #ProtectOakFlat march in Santa Fe, NM, 8/22/2015. Supporters of Save Oak Flat marched through Santa Fe streets and the local art markets this past weekend. United in an effort to bring awareness to the Save Oak Flat movement, protecting sacred sites, the land, the water, and cultural preservation. We had about 80+ people marching in solidarity, many of whom jumped in along the route. Please help Save Oak Flat, Arizona, and save Apache sacred ceremonial grounds from foreign copper mining. Support the Save Oak Flat Act-HR Bill 2811-to repeal the land exchange and visit www.apache-stronghold.com on how to help.We’re 75 to a hundred strong. We form two lines. Chanting, drumbeats, smell of sage, up Guadalupe we go, sparse traffic, Bobby limping slightly holding the Peltier banner, boys on skateboards. Up West San Francisco, Save Oak Flats, the Animas River, the San Juan River. Across Sandoval, up Palace, right through the Indian Market! Respectful reception, some raised fists, hat over heart, applause, Protect Sacred Sites, Water is Life, Free Leonard Peltier, John McCain is an Indian killer, smiles, thumbs up, pumping fists, people recording videos, hot sun in our faces, left hand angled over heart, join us, stand up, speak up, rise up. Around the plaza through every lane in the market, met with war cries. We form a circle, singing, spontaneous dancing. Down San Francisco, over Don Gaspar, down Water Street, back home to IFAM and booth number 500.

Melanie K. Yazzie, who’d driven up from Albuquerque with partner and fellow Red Nation co-founder Nice Estes, is at the Peltier booth. Taking it all in she turns to me and says: “If they were to pay attention to our political demands the entire narrative of New Mexican history would have to change…” These paintings belong in museums, especially here. Given the fact that Albuquerque is an important national location for Native American resistance, for Indigenous resistance, one would expect the museums in New Mexico to collect Peltier’s work. If they would exhibit his work they would have to contextualize the show politically, and viewers would perhaps be prompted to consider the erasure of his presence from his family and people.

Also at the booth is Kooper Indigenize Curley, a Hip Hop artist from the Diné Nation who’s been occupying Oak Flats since February 27th. He is most concerned about water. “They’re taking our water,” he says “What can we learn from water? How it’s free form. It’s way of resisting so gracefully that it’s effortless. The overcomings that water takes are like Leonard Peltier’s art. What we all strive for — patience, grace. We’re still breathing.” Together we look at a painting of a buffalo peering through a kitchen window. “The buffalo reminds me of the sacred symbol of the natural world. The window is the perception of this inside, which is a different home. The buffalo already gave us and lead us to our real home. Here he sees a different home — a dish, the soap, a clock, and he asks: What are they doing, why are they living like this!?” There’s a print of Leonard Peltier crouching in his jail cell. Kooper says, “It’s a self-portrait, he’s uncomfortable, he wants more light. He tries to follow this spectrum of light, when the sun is on his face, he’s content. The sun is letting him know, Life will continue.” Jerome Mark Williams, Caddo/Seminole, has been collecting signatures for the Clemency petition for all three days of the market along with AIM comrades Bobby and Sam, more than 25 pages worth. “He’s one of my AIM brothers, that’s why I do it. I’d do it for any of them. I feel he needs to be out of there. It’s looking bad, I heard he’s giving up. That’s what I heard, that he’s getting depressed. A lady came and told us that. She said write to him, send him cards, lift his spirits. When I heard that I thought, Everyone has to work harder to get him out! Everyone!” When Chauncey passes me the phone and says it’s his dad, all of the probing questions about stamina in the face of ultimate betrayal I’ve prepared fall away. I find I just want to ask him about one thing above all, because after three days of immersion into IFAM I was feeling it above all, and I want to share it with him — I ask him about love. “I have love for my people,” he says after a hearty laugh at the unorthodoxy of my approach. “For my family. I’ve done the best I could but my life has been all about incarceration. I’m proud of being a Native. I love the culture, the religion, I have always tried to be a loving parent. I show what love I can for them. My love is expressed in my paintings for the whole Indian world, but especially the future generations. We are the caretakers, we have to make a world worthy of them. The love of my people is why I was at Jumping Bull that day — to protect them.A band has started playing yards away on the mainstage rocking IFAM hard as it winds down in its final hour. Spontaneously, I break into a run with my notebook and pen, Chauncey’s cell pressed hard into my left ear, me near flying to the quieter edge of the Railyard Park. On the ground, in the scant shade, I ask Leonard about artmaking, if it serves to make incarceration more bearable? I’m swallowed whole by his response, disappearing down a hole of my own vast ignorance. IT IS NOT BEARABLE. EVERY MINUTE IS A TORTURE. It’s been pure hell for over 40 years. I hate every moment! I’m not used to it! I refuse to accept it!On cue we’re interrupted by a recording of an officious female voice saying: “This call is being placed from a federal prison.” I take a deep breath and try again. Art, I whisper, your art, tell me, please. And he does, he tells me how very core it is. I loved art from childhood. You have to understand, we lived under the worst poverty there was. We had to make our own toys — we’d draw, carve, make playthings from whatever we could. Art has always been my first love. I always wanted to be an artist/rock star. (That luscious laugh again.) We were always trying to live in two worlds.The recorded interruptions are humiliating enough, but then the call itself cuts off as I’m asking Leonard about one of the more evocative of his paintings hanging in the show. It’s a single horse grazing in a field. In the foreground it’s daytime and in the background, a moonlit night. In the gray hills at the horizon line there are images of wild horses and Natives with lassos trying to capture them. A vivid dreamscape, or so it seemed. I was terribly disappointed not to get the chance to hear Leonard talk about this piece.

But the most surprising thing happened. Two days later Chauncey forwarded an email from Leonard for me containing his comments on the picture. This is what he wrote: I was studying this picture of a horse someone sent me, and I was wondering what could this Horse be thinking about as it looked up from eating in this open field. Was it daydreaming, or what? So I got the idea that it could have been daydreaming about its ancestors when they were free and natives were capturing them, and they became like brothers and sisters, and loved and accepted each other as family members. Native Peoples became very close to their horses and horses became very close to them and they would die for each other. Some of the old timers of my day told stories of them being able to communicate with their horses. So hence, here it was daydreaming of the good old days! Doksha, All photos by Kerri Cottle, an educator, freelance and fine art photographer in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Frances Madeson is the author of the comic novel Cooperative Village (Carol MRP Co., New York, 2007), and a social justice blogger at Written Word, Spoken Word. Source URL |