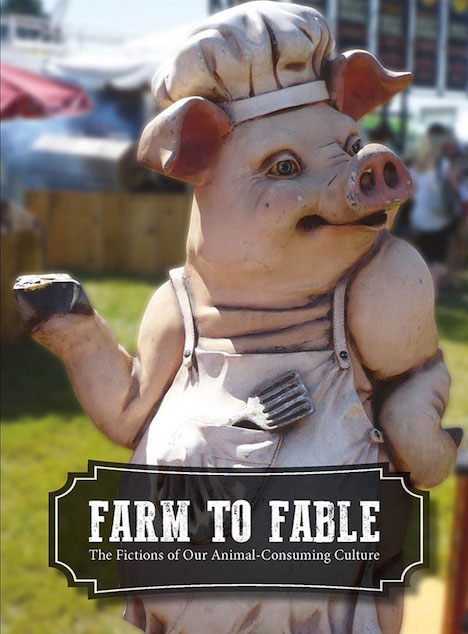

| Farm to Fable: The Fictions of Our Animal-Consuming Culture examines the foundations that support humanity's systematic assault on the identities, bodies and feelings of animals in order to consume them. We may agree with the author, Robert Grillo, director of Free from Harm, that the majority of people are "in denial," and that once the truth breaks through the barriers of denial, most people will see the animals for who they truly are and come to view meat, milk and eggs unfavorably. Suffused with the sense that "once I was blind, but now I see," they will end their participation in the greatest invisible horror show on earth. I say "participation" because animal product consumers are complicit, to varying degrees, in the manufacture of the "food fictions" Grillo analyzes. The consumer is not a blank slate on which the animal food production system imprints a false set of beliefs and practices. Taken together, the psychological, societal, cultural, historical, appetitive and commercial forces involved in animal product consumption form a constellation that can balk the animal advocate's effort to break through with "why this issue matters to us and building a convincing case for why it should matter to others."

As for the invisibility of the animals: here on the rural Eastern Shore of Virginia where I live, for example, you cannot not see the truckloads of chickens going up and down the roads to slaughter every day, but as one person told me after meeting a chicken rescued from the poultry industry at our sanctuary -- a person who has her own pet chickens -- you just accept, she said, that the chickens in the trucks are for food so you don't think about them. Throughout history there have been vegetarians and vegans, but we are at a point in Western culture where the entire enterprise of animal farming has begun to affect social consciousness as a problem. There is no way to fit the foot of Anastasia or Drizella into Cinderella's glass slipper. No way to produce zillions of land and water animals annually for human consumption without the industrial model; no way to industrialize animals humanely or sustainably. Some folks are starting to grasp this fact, and if it matters to them they will likely become vegetarians or vegans, or else they will look for ways to have it both ways by opting for green-washing, "the fiction that raising animals for food, even when compared to raising plants for food, can be done sustainably," and humane-washing, "animal agriculture's key strategy to intercept the conversation and deflect it away from veganism and retain consumers by using a sophisticated set of marketing fictions." Grillo in discussing green-washing and other fictions recounts the claims embedded in each and refutes them one by one. For example, there is not enough arable land and water on the planet to sustain the number of small farms and free-ranging animals that would have to exist in order to supply meat, milk and eggs to 7 billion-plus human beings. It isn't only the Temple Grandin brand of humane factory-farming fiction, or the Michael Pollan brand of humane Do-It-Yourself fiction that Grillo deconstructs; conventional animal welfare societies contribute to the delusion that we can devour animals endlessly, abundantly, sustainably, and humanely without "factory farming," a consummate falsehood. Farm to Fable reaches beyond the fabrications of mainstream consumerism and seductive advertising to how movies and TV shows portray nonhuman animals and the characters' attitudes toward them. As well, Grillo examines cliche's that infiltrate the animal advocacy movement, undermining our confidence and identifying us with fictions we need to combat. We become neurotically fearful of being and appearing "too morally pure," "too judgmental," "too privileged," "too emotional," and other No No's that distinguish the justice for animals movement, particularly for farmed animals, from other social justice movements.

For example, animal advocates have been criticized that our concern for animals is a privileged white people's "first-world concern," but as Grillo points out, "many other social justice issues have their roots in the first world too, like justice for sweatshop laborers, battered women, and date rape victims; gay rights and gay marriage; hate crime; bullying; and equal pay for women. But notice how advocates for these causes are never criticized as 'first world.' On the contrary, they are often lauded for their brave work to expose and fight against these injustices." "Leveraging Truth to Fight Fictions" Farm to Fable concludes with a chapter on "Leveraging Truth to Fight Fictions". I believe every animal advocate can benefit from this chapter. If you are a passionate advocate who winces when a colleague challenges: "Do you want results or do you want to be right?" this book is for you and for all of us. We may disagree with some of Robert Grillo's views, but we need to be conscious of our reasons for what we think and do in order to act constructively for animals, whose only hope of relief from us as a species is with those of us who are fighting for them. A question I have is whether we can realistically lump together farmers who raise and slaughter animals, and have done so for generations, with consumers who know farmed animals only as pieces of meat along with people who were once vegetarians or were not experienced in killing, but are now enthusiastic Do-It-Yourself slaughterers. Can we really lump together the majority of consumers of animal products as being "in denial"? This seems to me to be a handy but not very helpful explanation of what animals are up against, being too broad, basic and abstract to make sense of it all. Source URL |