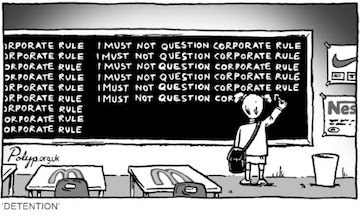

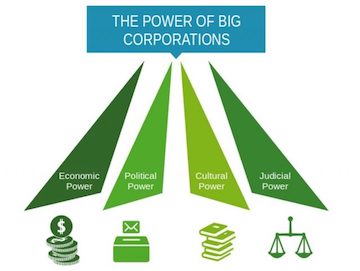

One of the most worrying aspects of the tendency that characterizes the current neoliberal globalization is undoubtedly the dismantling of labour, environmental, social and human rights, both in the Global South and in the Global North. It is a tendency that calls into question the rights of the peoples to freely decide their future and the sovereignty of states. This situation is the result of a new economic system and a new corporate logic conceived by the political/economic elites in western countries together with international economic and financial institutions, with the complicity of oligarchies in the Global South. At the same time, the rights of the most powerful actors in the current predatory capitalist system, transnational corporations, have been cemented. How did we get to this point? What instruments did these entities use to set up this economic and judicial architecture? And, more importantly, how can the peoples, the organizations and movements that struggle for social justice counteract this systematic, reactionary, anti-popular tendency? Economic context: neoliberalism and the Lex Mercatoria Starting in the 1970s, during the transition of the capitalist system from keynesianism to neoliberalism, transnational corporations were promoted to “drivers of development”. Specially since the imposition of Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP) in countries of the Global South, in the framework of the debt crisis. And this kicked off the period of privatization of large public corporations, the systematic deregulation of the national economic and industrial systems and of social and environmental protections. transnational corporations thus imposed themselves in the strategic sectors of the economies of indebted and “sick” countries [1]. Facing the “sickness” of debt, they were in need of “doctors” to find the appropriate medicine. And this is where international economic and financial institutions, like the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO, among others, join the fray. The sought-after “doctors” were in fact at the root of the disease. To this day, these same institutions contribute to keep the Southern countries in a state of permanent “sickness”. The conditions demanded of Southern countries (and also of some Northern ones in the framework of the current crisis) by these institutions always forced them to open their borders to transnational corporations. The medicines was thus administered. The task was simple: opening, liberalizing trade and accepting the dominant position of the powerful transnational corporations. The actions of these corporations had been associated to huge violations of rights and internal regulations of countries from the very beginning. The Lex Mercatoria In this context, and with the goal of assuring the survival of the neoliberal order, it was necessary to develop a judicial and regulatory framework to carefully protect transnational corporations. This framework is nowadays known as the Lex Mercatoria [2], through which the new international economic structure was formalized, with transnational corporate power front and centre. This opened the door for a new, private international law, set up to fit corporate power. A new legal system that challenged the democratic and popular character of international law: a legal system that prevails over international human rights law, over international labour regulations and over environmental regulations. In this sense, it should be clear that the law is being instrumentalised by political and economic elites, with goal of creating a juridical protection shield (coercive and binding) for their interests. Alejandro Teitelbaum, a jurist, explains it as follows: “Justice, or the law, is not some transcendental reference for an abstract human being, but the regulating system of social relations in a particular society in a given moment of its history, as a result of the correlation of forces between classes or groups at that time. This confers a high degree of relativism to the law and, depending on time and location, the law is referenced both in democratic societies founded upon principles of popular sovereignty and national sovereignty, and in autocratic, neocolonial or dictatorial systems. Therefore, to define what the law is, it is inevitable to do so from a political and ideological standpoint. If we recognise that the paradigm of the law is to set the rules of an ideal democratic society, and from that standpoint we recognise that the growing role and influence of transnational corporations over society in general is creating a corporate and neofeudal law, we are driven to the conclusion that said paradigm is in crisis. And if we are consistent, we will ensure that this new economic power conforms to the paradigm of a democratic society and not the other way around.” [3] Let us stress the following point: the backbone of the current capitalist system is corporate power. This power is not homogeneous, and it ought to be seen dialectically, as an ensemble of actors; those who wield political power (the representatives of the states) and those who wield economic power (corporations, banks, lobbies, etc). These two powers have merged in such a way that there is an arena where states, corporations, institutions, lobbies, work hand in hand to favour the interests of global capitalist elites. Today, this power is crystallised above all through the power of transnational corporations. Corporate power is multidimensional. It is first and foremost economic, because transnational corporations are monopolistic on economic, financial and commercial levels over most of the value, production and trade chains on an international scale; it is also political, because “the currency of transnational corporations are the close relations between political leaders and businessmen, one only has to look at the “revolving doors” that intertwine the political and corporate spheres” [4]; it is also cultural because the can influence our societies, our ideas and values, through communication and advertising techniques, in order to consolidate their power of persuasion in consumerism and neoliberal values; and as we have illustrated before, this power is also judicial.

Corporate power affirms itself internationally due to the existence of a very precise economic and trade regime. The trade and investment regime The reversal of popular social conquests that took place, and is still taking place, in the framework of the spreading of the neoliberal system to the entire world through a new regime of trade and investment that is controlled by corporations. As we have stressed, this new framework was developed side by side with a new judicial framework to perpetuate the grasp of this new system. We now pose the central question of this article: What is this trade and investment regime? How should it be fought and what alternatives can be put forward? A multitude of free trade and investment agreements (bilateral, regional or multilateral) are part of this regime. These agreements have progressively dismantled, hollowed and taken down the precedence of international and national regulations, in favour of transnational corporations and international capital [5]. By virtue of having won this battle for legal supremacy, this system has been able to take down the sovereignty of states, attacking them when they decide to implement economic and/or social policies that are against the interests of corporate interests. In this manner, transnational corporations keep acting with total impunity, with no accountability for their crimes and violations. In other words, this web of treaties works as a system of “communicating vessels” that allow for neoliberal policies to circulate and specially penetrate and impose themselves in national economies [6]. It is “thanks” to clauses in these agreements that the countries in the Global South entered the neoliberal globalization game. The central element of the free trade and investment agreements is their coercive and binding character, necessary to ensure their full implementation. As we have said before, international law, as well as national constitutions, become subordinated to these agreements. And in case of non-compliance, mechanisms of political coercion spring up: pressure, economic and diplomatic sanctions, and if necessary, even coups or military interventions (sometimes labelled as “humanitarian” interventions) [7]. Moreover, in the framework of these treaties, transnational corporations benefit from legal provisions that state the possibility of recurring to arbitration mechanisms to settle disputes between investors and states. In said mechanisms, corporations can sue states in these arbitration courts (for example the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID)) to defend and even impose their interests and trade rights. However, the reverse scenario is not allowed. States are not allowed to bring corporations to court in case of violations of national or international law, in cases of crimes of violations of the fundamental rights of their peoples. We witness cases of states being persecuted and forced to pay fines that can reach billions of dollars, for having decided to implement measures to improve infrastructure, labour conditions, environmental protection, etc [8]. In other words, states are deprived of their own sovereignty and in exchange the ability of corporations to interfere in these matters is enhanced. What is to be done? This is the dominant and ever-present question in the current context. The Global Campaign to Reclaim Peoples Sovereignty, Dismantle Corporate Power and Stop Impunity (a coalition of over 200 organizations, social movements, trade unions, peasant organizations, etc) has put forward concrete proposals to this end. These were produced during the negotiations at the UN about the introduction of a binding judicial instance over transnational corporations and human rights. The Global Campaign issued the following proposals:

The Global Campaign, as a platform representing the peoples affected by corporate power, is playing its part with concrete proposals, such as the ones listed above, to put an end to this trade and investment regime that generates injustice and crimes. Thanks to their efforts, the narrative proposed by the Global Campaign has been more and more included in the negotiation table. Many countries have embraced this narrative and made it their own. It is necessary to keep up the pressure and create the necessary correlation of forces to ensure that this process triumphs, thus contributing to the popular interests of countries and peoples around the world. It is a historic process, with an enormous challenge. In truth, it is not only the fundamental rights of the peoples and the environment that are at stake, but democracy as a whole. Notes : [1] Melik Özden, Transnational corporations’ impunity, CETIM, 2016, p. 15 [2] Juan Zubizarreta y Pedro Ramiro, Contra la lex mercatoria, Icaria, 2015. (in Spanish) [3] Alejandro Teitelbaum, La armadura del capitalismo. El poder de las sociedades transnacionales en el mundo contemporáneo, Icaria, 2010. (in Spanish) [4] OMAL, El poder corporativo, http://omal.info/spip.php?article5568. (in Spanish) [5] Juan Hernández Zubizarreta, The new Global Corporate Law, State of Power 2015, Transnational Institute, 2015, https://www.tni.org/en/briefing/new-global-corporate-law [6] Alejandro Teitelbaum, International, regional, sub-regional and bilateral free trade agreements, Critical Report no. 7, CETIM, 2010 [7] Idem [8] UNCTAD database of the known trade agreements around the world: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/ISDS [9] http://www.stopcorporateimpunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/SIX-points_ENG.pdf Translated from Spanish by Ricardo Vaz for Investig’Action Source: ALAINET (Revista América Latina en Movimiento), Transnacionales y Derechos Humanos Source URL |