| Most people missed it but America’s intelligence services also looked recently at developments in the world economy. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) published its latest assessment, called Global Trends: The Paradox of Progress, which “explores trends and scenarios over the next 20 years”. The DNI concludes that the world is “living in paradox – industrial and information age achievements are shaping a world both more dangerous and richer with opportunity. Human choices will determine whether promise or peril prevails.” The DNI praises capitalism over the last few decades for “connecting people, empowering individuals, groups, and states and lifting a billion people out of poverty in the process.” But American capital’s eyes and ears are worried about the future. There have been worrying “shocks like the Arab Spring, the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, and the global rise of populist, anti-establishment politics. These shocks reveal how fragile the achievements have been, underscoring deep shifts in the global landscape that portend a dark and difficult near future.” All these developments are bad things for global capital and American supremacy, it seems. And the DNI reckons that things are not going to get better. “The next five years will see rising tensions within and between countries. Global growth will slow, just as increasingly complex global challenges impend.” What is the answer? Well, this comment from the DNI report is unvarnished: “It will be tempting to impose order on this apparent chaos, but that ultimately would be too costly in the short run and would fail in the long. Dominating empowered, proliferating actors in multiple domains would require unacceptable resources in an era of slow growth, fiscal limits, and debt burdens. Doing so domestically would be the end of democracy, resulting in authoritarianism or instability or both. Although material strength will remain essential to geopolitical and state power, the most powerful actors of the future will draw on networks, relationships, and information to compete and cooperate. This is the lesson of great power politics in the 1900s, even if those powers had to learn and relearn it.” In other words, while it would be better to just crush opposition and “impose order” in America’s interests, this is probably not possible with a weak world economy and lack of funds. Better to try “draw on networks, relationships and information” (ie spy and manipulate) to get “cooperation”. But it is not going to be easy to sustain America’s dominance and the rule of capital, the DNI report concludes, as globalisation “hollowed out Western middle classes (read working classes) and stoked a pushback against globalization.” Moreover, “migrant flows are greater now than in the past 70 years, raising the specter of drained welfare coffers and increased competition for jobs, and reinforcing nativist, anti-elite impulses.” And “slow growth plus technology-induced disruptions in job markets will threaten poverty reduction and drive tensions within countries in the years to come, fueling the very nationalism that contributes to tensions between countries.” You see, the problem is that the population of America and its capitalist allies are getting older and the new powers have younger, more productive populations. Yet capitalism cannot deliver for these growing populations in the so-called ‘developing countries’. Meanwhile, “automation and artificial intelligence threaten to change industries faster than economies can adjust, potentially displacing workers and limiting the usual route for poor countries to develop.” And then there is climate change and environmental disasters that will entail. This is all going to “make governing and cooperation harder and to change the nature of power—fundamentally altering the global landscape.” So it is not a pretty picture beneath all the optimistic talk and fanfare we heard from the rich elite at Davos only last month. Instead, the DNI reckons “challenges will be significant, with public trust in leaders and institutions sagging, politics highly polarized, and government revenue constrained by modest growth and rising entitlement outlays. Moreover, advances in robotics and artificial intelligence are likely to further disrupt labor markets.” The DNI tries to sound hopeful at the end of this litany of dangers to global capitalism but they are not convincing. I have posted before about the clear signs that the age of globalisation and capital’s expansion at the expense of labour everywhere appears over. Another indicator of this was a report from the US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) and the Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics. The report found that trade misinvoicing and tax havens mean the world’s givers are more like takers. The GFI tallied up all of the financial resources that get transferred between rich countries and poor countries each year: not just aid, foreign investment and trade flows but also non-financial transfers such as debt cancellation, unrequited transfers like workers’ remittances, and unrecorded capital flight (more of this later). What they discovered is that the flow of money from rich countries to poor countries pales in comparison to the flow that runs in the other direction. In 2012, the last year of recorded data, developing countries received a total of $1.3tn, including all aid, investment, and income from abroad. But that same year some $3.3tn flowed out of them. In other words, developing countries sent $2tn more to the rest of the world than they received. If we look at all years since 1980, these net outflows add up to $16.3tn – that’s how much money has been drained out of the global south over the past few decades. Developing countries have forked out over $4.2tn in interest payments alone since 1980 – a direct cash transfer to big banks in New York and London, on a scale that dwarfs the aid that they received during the same period. Another big contributor is the income that foreigners make on their investments in developing countries and then repatriate back home. But by far the biggest chunk of outflows has to do with unrecorded – and usually illicit – capital flight. GFI calculates that developing countries have lost a total of $13.4tn through unrecorded capital flight since 1980. Most of these unrecorded outflows take place through the international trade system. Basically, corporations – foreign and domestic alike – report false prices on their trade invoices in order to spirit money out of developing countries directly into tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions, a practice known as “trade misinvoicing”. Usually the goal is to evade taxes, but sometimes this practice is used to launder money or circumvent capital controls. In 2012, developing countries lost $700bn through trade misinvoicing, which outstripped aid receipts that year by a factor of five. But now global trade growth has slowed to a trickle and capital flows are also falling back. It has become just that more difficult for multi-nationals and banks to exploit the global south as a way to boost profitability from its decline in the global north.

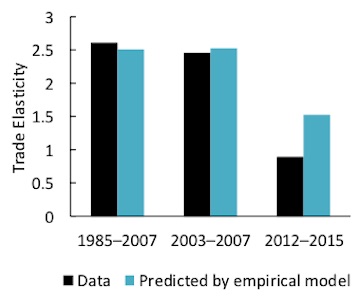

The ratio of import growth to real GDP growth in the major economies has fallen back sharply.

The DNI report suggests that increased rivalry over the spoils of imperialism in the 1900s led to a world war. The DNI reckons that “Although material strength will remain essential to geopolitical and state power, the most powerful actors of the future will draw on networks, relationships, and information to compete and cooperate”. Compete and cooperate? And Trump in the presidency? Source URL |