| Editor's Note: The article below provides an interesting - and accurate - history of modern diamond processing. It does not, however, suggest - even vaguely - that much of the productivity of these diamond mines has been - and continues to be - possible because the use of slave or poorly paid black workers. - prh, ed. WHAT IS A DIAMOND? A diamond (from the ancient Greek– adámas – meaning “unbreakable”, “proper”, or “unalterable”) is one of the best-known and most sought-after gemstones. A diamond is a mineral not a rock, an allotrope, or a form, of the element carbon – a diamond is actually carbon in its most concentrated form. It requires enormous pressure (45-60 kilo bars) and heat of up to 1000 degrees centigrade and beyond to create. Such conditions over billions of years creates diamonds deep inside the mantle of the earth, at depths of between 140km and 190km. They are generally found on surface only in ancient geological areas of the globe known as cratonic regions and brought to the surface in deep-origin volcanic eruptions in which the magma originates from these enormous depths. This kind of volcano is very rare, as magma from most volcanoes originates from much closer to the surface. Diamonds themselves are extraordinary. Carbon atoms, in this heat and pressure, are formed into what’s called a diamond lattice, and as such exhibit some extraordinary physical properties. The hardness of diamond and its high dispersion of light—giving the diamond its characteristic “fire”—make it the most desirable gem for jewellery while industrial quality making up most productions have a surprising number of useful applications in industry, telecommunications, medicine and science. That incredibly strong lattice structure also makes it hard for impurities to find their way into diamonds, although inclusions do occur and coloured diamonds are a result of where elements such as boron have crept in. And so, if you own a diamond, it’s worth considering the billions of years and the geological journey it has taken from deep in the planet to reach the jewellery piece it adorns…

THE ALLURE OF DIAMONDS Diamonds have been sought out and coveted throughout human history, with mention being made of a diamond trade as far back as over 2000 years ago in ancient Indian texts. Roman texts also mention diamonds as great tools for engraving metal. After the trade from the source in India into Europe during the 13th century they remained, for centuries the jewels only of the wealthiest of royalty. In the 1700’s some diamonds were found in South America, but in relatively small quantities and India remained the principle source of the rare stones. Today’s global diamond industry which directly and indirectly benefits about 10 million people traces its origins to another continent where it has been the foundation of economies ignited by the discovery of these treasures from the depths of the planet. ERASMUS JACOBS

That all fundamentally changed when in the summer of 1866 a 15-year-old boy named Erasmus Jacobs stumbled across a brilliant stone on the western bank of the Orange River on his father’s farm De Kalk in the then-Cape Colony. That stone was a 21.25-carat diamond, now known as the Eureka. It is the first diamond ever discovered and authenticated as such anywhere is Africa. After having several owners it was purchased abroad and bought back by De Beers in 1967 to be presented to the Speaker of Parliament and placed on permanent public exhibition in The Diamond Vault at The Big Hole exhibition centre. DIAMOND RUSH

A few small discoveries followed without too much anticipation that the country was on the brink of a history changing discovery set to ignite a diamond rush in 1869 unlike any seen before or since. A Griqua herdsman named Zwartbooi discovered a 83.5 carat diamond which he sold for 500 sheep, 10 cattle and a horse. It was later named The Star of South Africa. The discovery triggered the first diamond rush to the Orange River diggings and later inland to New Rush – or the dry diggings – where today stands the capital of The Northern Cape – Kimberley. The diamond is exhibited in London’s Natural History Museum. KIMBERLEY

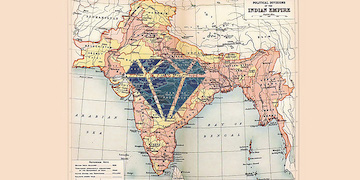

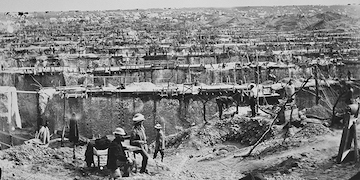

Within weeks of the diggers moving north and discovering significant numbers of diamonds in what became, between November 1869 and July 1871 four major diamond mines they set up the Dry Diggings. Claims were organised, mapped and traded – and the beginning of a tent town was laid out. Thousands of men were digging, and exploring for other deposits nearby. In 1871 a diamond was discovered on a Koppie (small hill) – actually the remnants of a long-extinct volcano – quickly reducing it what would eventually become Kimberley’s Bill Hole which produced 14 million carats before ceasing production in 1914. This marked a dramatic change in the history not only of mines, but also in South Africa, where enormous fortunes were quickly made and lost in the world’s first industrial type diamond mine, and interest – political and otherwise – in the Cape Colony, long a backwater of the British Empire, was suddenly aroused. CECIL RHODES

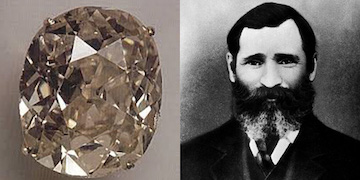

The various companies and claims were combined as economic necessity dictated to finance the increasing deep, complex and more expensive to operate mines. By the mid-1880s more sizable companies operated until eventually two enormous concerns – the Kimberley mine, under Barney Barnato, and the De Beers mine, under Cecil Rhodes competed for control of the diamond mines. When Rhodes persuaded Barnato to sell his shares, Rhodes’ De Beers Consolidated Mines eventually controlled the Kimberley diamond mines and he was to become one of the richest men on earth and a politician driven by his desire to expand the British Empire. CULLINAN DIAMOND

In 1905, the Cullinan Diamond – a 3106 carat giant gemstone – was found in the mine wall at the Premier mine (renamed The Cullinan Diamond Mine in 2003). It was cut into nine principal gems the largest of which form a part of the British Crown Jewels. Another 96 small brilliant cut diamonds were also cut some of which were distributed as gifts. The rough diamond had been bought from the owners of The Premier mine by the Colonial Government of the Transvaal with funds also raised by public subscription to present to King Edward VII to commemorate the granting of Responsible Government to The Transvaal so soon after the end of the brutal Anglo Boer War in 1902. It was a gift of peace and reconciliation and was accepted by the King at Windsor Castle on 21 November 1908. The diamonds are exhibited in The Tower of London. A DIAMOND IS FOREVER

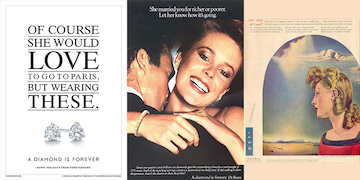

In 1947, an American advertising copywriter Frances Gerety came up with the tagline ‘A diamond is forever’, cementing De Beer’s place as the home of diamonds. These days the diamond industry produces about 130-million carats a year. It’s a truly global industry with enormous diamond cutting operations in India and specialist factories cutting few but high value diamonds in South Africa, Botswana and Namibia as well as trading also in Belgium, Israel and the United Arab Emirates. DE BEERS

Today De Beers continues to sort its entire South African production in Kimberley having sold its mine to a Kimberley based consortium able to operate it profitably for longer into the decade ahead. De Beers mine diamonds across the world, in Botswana, Namibia and Canada and in South Africa it has the Voorspoed mine in the Free State and the Venetia mine in Limpopo provinces. It may be the biggest diamond miner on earth, but South Africa is still where its roots are. ALTERNATE USES FOR DIAMONDS We are all familiar with the beauty of a diamond set in an engagement ring, earrings, a pendant, and other fine jewellery. However, due to their superior strength as the hardest naturally occurring substance on the planet and unique properties, diamonds can be used for a number of different purposes, from industrial, to beauty, audio equipment and health products. ABRASIVEBENEFICIATION Once mined, diamonds go through the process of being sorted, graded and valued. They are then sold, polished and eventually end up in the care of jewellers, who will, with great skill and artistry, create the jewellery in which the diamond form the center piece. Sorting and cutting of diamonds is considered in economic terms to be beneficiation, the process – according to the Department of Mineral Resources – of “value-added processing”. This “involves the transformation of a primary material (produced by mining and extraction processes) to a more finished product, which has a higher export sales value.” This kind of activity is good for the economy and can additionally upskill workers and add value for the country. In order to address historical exclusion and to encourage the industry in South Africa to be more globally competitive and compete with larger cutting centres, De Beers has embarked on a process to nurture and support black-owned diamond-cutting businesses. This, it is hoped, will develop skills and grow the industry in South Africa. Last year, in partnership with the Department of Mineral Resources, De Beers selected five black-owned diamond beneficiators for support so that they might “better compete on the world diamond stage”. The company’s CEO, Bruce Cleaver, said that if the company was able to “lay a successful platform for developing young beneficiators, then this programme will go a long way towards creating a sustainable and meaningful diamond development pathway for other young local cutters and polishers for many years to come”. There is a great deal of work to be done between getting a diamond out of the ground and it adorning a piece of jewellery – De Beers is doing what it can to make sure that black-owned South African companies are at the heart of this work. TIME TO REFLECT In 2017, Anglo American—De Beers’ parent company—is marking a significant milestone: 100 years of operation. This centenary celebration gives them the opportunity to look back at the history and heritage that has shaped them since 1917 when its founder, Ernest Oppenheimer launched the business. For a century, Anglo American has occupied a special place in South Africa’s social and economic fabric. The company, which at its height, controlled over 60% of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), is now a totally different beast to the big South African conglomerate with once “tentacles” in almost every sector of the South African economy. Now, 100 years later, Anglo American occupies the global market as a global diversified miner with interests in a diverse asset portfolio spanning a number of continents, including: South America, North America, and Australia, in addition to Africa. With its roots firmly in South Africa, the company has not only transformed itself, but also contributed to the transformation of South African society, through spearheading the creation of some of South Africa’s most significant black economic empowerment mining companies—like Exxaro, African Rainbow Minerals and Royal Bafokeng—while contributing substantively to improving health, education and enterprise development in its host communities. As they look at their journey so far, they reflect on what makes them different today as well as looking ahead at how they will create a sustainable future as partners with our communities, employees and shareholders. Source URL |