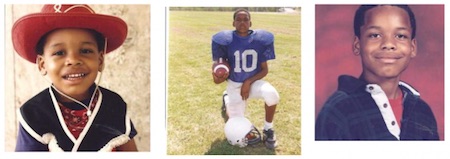

Note: Christopher Young is on death row at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas, listed in 2013 as one of America’s 10 worst prisons. He has an execution date of July 17, 2018. Young, 34, was sentenced to death in 2006 for the 2004 murder of 55-year-old convenience store owner Hasmukhbhai “Hash” Patel. Young’s lawyers claim religious discrimination occurred during the jury selection process of his trial, and over 500 religious leaders signed a statement saying he deserved a new trial. In January 2018, the United States Supreme Court turned down Young’s latest appeal. He seeks clemency. “Christopher Young, you’ve been sentenced to die by the state of Texas. May God have mercy on your soul.” I sat in the chair next to my attorneys looking up at the black-robed white man telling me I’m going to die. I’m numb. I faintly hear a gasp behind me coming from the crowd, which I later learn is my mother fainting from the news. I look around, and my eyes stop on the 12 people that have made the decision on my life. Twelve people that probably will never think about me again once they go home. I see zero reaction on their faces from the news. I then see my attorneys and prosecutors shaking hands, smiling at one another while slapping each other on the back. All of this is a blur. Sheriffs in freshly pressed uniforms snap gleaming cuffs on my wrist and escort me from the spectacle. As I sit in a cell alone, I had one thought: I am going to death row, and I need to get my mind together to survive in prison, especially a place like death row.

Growing up in a lower-class, gang-ridden neighborhood, and being a gang member, going to prison was a rite of passage. We sat at the feet of ex-cons listening to their stories like they were the answer to the great algorithm of surviving prison. We told and retold these stories like they were our own. We hoped our stories to our kids would be even better. That was the view of prison. It was a stop that had to be made on the journey to becoming a man. Arriving on death row was an experience. I was ready for any confrontation with anybody. I was 22 years old and was angry at the show in the courtroom and the world for all of my problems. My father being murdered. My relationship with my mother. The world making me turn to drugs. Everything. I was angry no one wanted to listen to what really happened the day of the crime and was ready to take it out on anyone who looked at me the wrong way. I was placed in a 6-foot-by-l0-foot cell with a sink/toilet combo, a metal slab to use as a bed, and two tables protruding from the walls. The cell smelled like feces from the last occupant and was a drab gray color. I took two steps toward the back of the cell, turned around and took two step back toward the front. I paced like this around 15 minutes, mentally getting myself ready to be let out with the others and fight when I had to. All of the stories I’ve heard was about fighting. You were going to fight on the first day because once people found out you were in a gang, they’re going to want to test you. I was ready. As I was pacing, I heard my cell number being called by someone I couldn’t see but could hear a few cells down the walkway. Being taught not to respond to a cell number, but also knowing they didn’t know my name, I answered, “My name ain’t 61 cell. Call me Lunatik,” giving him the name I picked up before I came to prison. “Well, Lunatik, what you bang?” He was asking if I was in a gang. This is the first test I was expecting. I responded to him that I was a Blood from San Antonio—but didn’t give him any details—and that we’ll talk about it when we meet on the recreation yard. After I said that, I heard some laughs and a few snickers from men in other cells. I got mad and continued pacing my cell. It didn’t take long to learn how death row operates. It’s nothing like I’ve heard about in any other prison. None of the stories prepared me for this. I never went to the recreation yard with any other prisoner. So the fight I expected to have never happened. I was locked in my cell 23 hours out of the day, as I’ve been for 13 years. Anytime I went to recreation, I was there by myself. The interactions I ended up having with the other prisoners involved talking about how we grew up, what happened in their trial, sharing legal work, debating social subjects. These were men from different walks of life: black men, white men, Latin men and Asians. Men from numerous different gangs, from numerous different cities and states. Men from different countries. All of us had one thing in common. We were all sentenced to die and have all been through the trial process, where all the power of speaking for yourself about your life is taken away from you. All of us have felt powerless at least once in our life. Death row is a community. A weird one if you’ve never learned about it, but it’s a community. It was being a part of this community that I started learning more about myself and my self-worth to others and the bigger community on the outside. I didn’t have to grandstand, be defensive, or let pokes at my insecurities trigger my anger. I could grow. When I first met Reginald Blanton, I saw a kindred spirit. He was from San Antonio like I am. Grew up in a broken household and in the streets. Our only difference was he was a Crip and I was a Blood, which in reality is one and the same. We clicked immediately. He was nothing like any other “gang member” I had met before. When I first asked him for something to read, I expected an action book, some type of thriller, fiction, urban fiction, or even fantasy. That’s not what I got from him. The first book Reg ever sent me was “Breaking the Chains of Psychological Slavery” by Na’im Akbar. This book started the growth process in me. It made me look in the mirror at the way I acted and how my actions are connected to the days of slavery. Who wants to act like that? From there, he would send me book after book on growth that helped me change my approach on life. He taught me how to talk to people without any malice or anger and how being patient with others can help you get a better conversation and get things done. Reg made you want to better yourself. When Reg was executed, it was a shock to my system. I knew I had to continue to better myself for me and my kids [Christopher has three daughters, ages 17, 13 and 13—Editor]. A lot of the old ways, I left behind. My anger wasn’t completely gone at that time, but I was working on it. I started thinking about my mentor program, Reaching Our Young: From the Inside Out. What inspired me to do this was looking at myself in the mirror and knowing where I came from. There’s numerous other boys and girls that came from where I came from that needed help. So instead of having them sit at my feet, listening to stories of prison like I did with older ex-cons, I wanted them sitting in front of me, learning about growth and that the process doesn’t have to involve prison. I wanted them to see there was nothing wrong with growing up and being responsible for yourself and anything around you in a positive way. I knew that’s what youngsters needed. So I was willing to try and provide that. I also knew doing this would help me. I knew I had to get away from the “Lunatik” I was in the world. This is what made me adopt the Swahili name “Jasiri Kulinda Watu,” meaning “Fearless Protector of the People.” It was therapy for me to help these kids. These young kids would help me become more responsible and aware of my actions because I had to be everything I was telling them they should be. That included leaving the gang life alone.

Over the years, I’ve slowly worked on my anger. I stopped blaming everybody else for my problems. I recognized what alcohol and drugs did to my thinking, mood and mentality. People would say leaving all of the drugs and alcohol alone was easy to do, because I’m in prison, but they need to understand drugs and alcohol are still available in abundance in prison like they are in the streets. Prison is just a microcosm of the streets. Once I admitted to myself all of these faults, faults people have been pointing out to me for years, I had the chance to grow out of the old ways. Death row saved my life. I truly believe if I would not have come to death row when I did, I would be one of two places: in prison or murdered in the streets. If I would have gone straight to prison with the attitude I had, my growth process would not have started, and my gang-banging ways would still be there. I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to look at myself and tell myself I was doing wrong. I wouldn’t have been able to help anybody. Now, if I’m sent to prison with the mindset I have, I can help other individuals through their growth process. Kids and grown men. Gang members who are conflicted with the loyalty to their gang and the loyalty to themselves. I can help them overcome that conflict. I did it. The road to growth and maturity starts inside you. With all types of vices around to block that road, there’s no way you can continue down that path. If you’re living for someone else and living by their rules and it’s always negative, then you’ll never grow and do better for yourself and the ones that love you. Death row saved my life. Without coming to death row, I would not be the man I am today. I would not be able to raise my kids, or help other kids. We’re quick to throw things away. I’m truly sorry for the crime I committed. There’s nothing I can do to bring back Mr. Hash Patel. If I knew taking my life would do that, I’d volunteer for it without any complaints. But that’s not going to do it. I can teach others to think about their actions. I’m sure I can stop something like this from happening again. Death row saved my life. Please help save my life. #SAVECHRISYOUNG -----

In Texas, the governor must have the recommendation of clemency from a board or advisory group. Learn more about clemency here and here. The contact information for the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles is: Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles PO Box 13401 Austin, Texas 78711-3401 512-406-5452 bpp-clemency@tdcj.texas.gov The contact information for the governor of Texas is: Governor Greg Abbott Office of the Governor PO Box 12428 Austin, TX 78711-2428 512-463-2000 Write directly to Christopher Young. His contact information is: Christopher Young TDCJ #999508 Polunsky Unit, 3872 FM 350 S., Livingston, TX 777351 Source URL |