| Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”? Below is the fifteenth installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. * * *

The United States of America conquered half of Mexico. There isn’t any way around that fact. The regions of the U.S. most affected by “illegal” immigration—California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas—were once part of the Republic of Mexico. They would have remained so if not for the Mexican-American War (1846-48). Those are the facts, but they hardly tell the story. Few Americans know much about this war, rarely question U.S. motives in the conflict and certainly never consider that much of America’s land—from sea to shining sea—was conquered. Many readers will dispute this interpretation. Conquest is the natural order of the world, the inevitable outgrowth of clashing civilizations, they will insist. Perhaps. But if true, where does the conquest end, and how can the U.S. proudly celebrate its defense of Europe against the invasions by Germany and/or the Soviet Union? This line of militaristic reasoning—one held by many senior conservative policymakers even today—rests on the slipperiest of slopes. Certainly nations, like individuals, must adhere to a certain moral code, a social contract of behavior. In this installment I will argue that American politicians and soldiers manufactured a war with Mexico, sold it to the public and then proceeded to conquer their southern neighbor. They were motivated by dreams of cheap farmland, California ports and the expansion of the cotton economy along with its peculiar partner, the institution of slavery. Our forebears succeeded, and they won an empire. Only in the process they may have lost something far more valuable in the moral realm.

(Mis)Remember the Alamo!: Texas and the Road to War We all know the comforting tale. It has been depicted in countless Hollywood films starring the likes of John Wayne, Alec Baldwin and Billy Bob Thornton. “Remember the Alamo!” It remains a potent battle cry, especially in Texas, but also across the American continent. In the comforting tale, a myth really, a couple of hundred Texans, fighting for their freedom against a dictator’s numerically superior force, lost a battle but won war—inflicting such losses that Mexico’s defeat became inevitable. Never, in this telling, is the word “slavery” or the term “illegal immigration” mentioned. There is no room in the legend for critical thinking or fresh analysis. But since the independence and acquisition of Texas caused the Mexican-American War, we must dig deeper and reveal the messy truth. Until 1836, Texas was a distant northern province of the new Mexican Republic, a republic that had only recently won its independence from the Spanish Empire, in 1821. The territory was full of hostile Indian tribes and a few thousand mestizos and Spaniards. It was difficult to rule, and harder to settle—but it was indisputably Mexican land. Only, Americans had long had their eyes on Texas. Some argued that it was included (it wasn’t) in the Louisiana Purchase, and “Old Hickory” himself, Andrew Jackson, wanted it badly. Indeed, his dear friend and protégé Sam Houston would later fight the Mexicans and preside as a president of the nascent Texan Republic. Thirty-two years before the Texan Revolution of Anglo settlers against the Mexican government, in 1803, Thomas Jefferson had even declared that [the Spanish borderlands] “are ours the first moment war is forced upon us.” Jefferson was prescient but only partly correct: War would come, in Texas in fact, but it would not be forced upon the American settlers. Others besides politicians coveted Texas. In 1819, a filibusterer (one who leads unsanctioned adventures to conquer foreign lands), an American named James Long, led an illegal invasion and tried but failed to establish an Anglo republic in Texas. Then, in 1821, Mexico’s brand new government made what proved to be a fatal mistake: It opened the borders to legal American immigration. It did so to help develop the land and create a buffer against the powerful Comanche tribe of West Texas but stipulated that the Anglos must declare loyalty to Mexico and convert to Catholicism. The Mexicans should have known better. The Mexican Republic abolished slavery in 1829, more than three decades before its “enlightened” northern neighbor. Unfortunately nearly all the Anglo settlers, who were by now flooding into the province, hailed from the slaveholding American South and had brought along many chattel slaves. By 1830, there were 20,000 American settlers and 2,000 slaves compared with just 5,000 Mexican inhabitants. The settlers never intended to follow Mexican law or free their slaves, and so they didn’t. Not really anyway. Most officially “freed” their black slaves and immediately forced them to sign a lifelong indentured servitude contract. It was simply American slavery by another name. After Santa Anna—Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón, an authoritarian but populist president—seized power, his centralizing instincts and attempts to enforce Mexican policies (such as conversion to Catholicism and the ban on slavery) led the pro-autonomy federalists in Texas (most of whom were Americans) to rebel. It was 1835, and by then there were even more Americans in Texas: 35,000, in fact, outnumbering the Hispanics nearly 10 to 1. Many of the new settlers had broken the law, entering Texas after Santa Anna had ordered the border closed, as was his sovereign right to do. What followed was a political, racial and religious war pitting white supremacist, Protestant Anglos against a centralizing Mexican republic led by a would-be despot. The Texan War of Independence (1835-36) was largely fought with American money, American volunteers and American arms (even then a prolific resource in the United States). The war was never truly limited to Texas, Tejanos or Mexican provincial politics. It was what we now call a proxy war for land waged between the U.S. and the Mexican Republic. Furthermore, though Santa Anna was authoritarian, certain Texans saw him as their best hope for freedom. As Santa Anna’s army marched north, many slaves along the Brazos River saw an opportunity and rebelled. Most were killed, some captured and later hanged. And, while slavery was not, by itself, the proximate cause of the Texan Rebellion, it certainly played a significant role. As the Mexican leader marched north with his 6,000 conscripts, one Texas newspaper declared that “[Santa Anna’s] merciless soldiery” was coming “to give liberty to our slaves, and to make slaves of ourselves.” So, once again—as in America’s earlier revolution against Britain—white Americans clamored about their own liberty and feared to death that the same might be granted to their slaves. When (spoiler alert) Santa Anna’s army was eventually defeated, the Mexican retreat gathered numbers as many slave escapees and fearful Hispanics sought their own version of “freedom” south of the Anglo settlements. Surely, the most evocative image of the Texas War of Independence was the heroic stand of 180 Texans at the Alamo. “Alamo” has entered the American lexicon as a term for any hopeless, yet gallant, stand. And, no doubt, the outnumbered defenders demonstrated courage in their doomed stand. The slightly less than 200 defenders were led by a 26-year-old failed lawyer named William Barret Travis and included the famed frontiersman Davy Crockett, a former Whig member of the U.S. House of Representatives. All would be killed. Still, the battle wasn’t as one-sided or important as the mythos would have it. The defenders actually held one of the strongest fortifications in the Southwest, had more and superior cannons than the attackers and were armed mainly with rifles that far outranged the outdated Mexican muskets. Additionally, the Mexicans were mostly underfed, undersupplied conscripts who often had been forced to enlist and had marched north some 1,000 miles into a difficult fight. Despite inflicting disproportionate casualties on the Mexicans, the stand at the Alamo delayed Santa Anna by only four days. Furthermore, despite the prevalent “last stand” imagery, at least seven defenders (according to credible Mexican accounts long ignored)—probably including Crockett himself—surrendered and were executed. None of this detracts from the courage of any man defending a position when outnumbered at least 10 to 1, but the diligent historian must reframe the battle. The men inside the Alamo walls were pro-slavery insurgents. As applied to them, “Texan,” in any real sense, is a misnomer. Two-thirds were recent arrivals from the United States and never intended to submit to sovereign Mexican authority. What the Battle of the Alamo did do was whip up a fury of nationalism in the U.S. and cause thousands more recruits to illegally “jump the border”—oh, the irony—and join the rebellion in Texas. Eventually, Santa Anna, always a better politician than a military strategist, was surprised and defeated by Sam Houston along the banks of the San Jacinto River. The charging Americans yelled “Remember the Alamo!” and sought their revenge. Few prisoners were taken in the melee; perhaps hundreds were executed on the spot. The numbers speak for themselves: 630 dead Mexicans at the cost of two Americans. It is instructive that the Mexican policy of no quarter at the Alamo is regularly derided, yet few north of the Rio Grande remember this later massacre (and probable war crime). Still, Santa Anna was defeated and forced, under duress (and probably pain of death), to sign away all rights to Texas. The Mexican Congress, as was its constitutional prerogative, summarily dismissed this treaty and would continue its reasonable legal claim on Texas indefinitely. Nonetheless, the divided Mexican government and its exhausted army were in no position (though attempts were made) to recapture the wayward northern province. Texas was “free,” and a thrilled—and no doubt proud—President Jackson recognized Houston’s Republic of Texas on “Old Hickory’s” very last day in office. Thousands more Americans flowed into the republic over the next decade. By 1845, there were 125,000 (mostly Anglo) inhabitants and 27,000 slaves—that’s more enslaved blacks than Hispanic natives! One result of the war was the expansion and empowerment of the American institution of slavery. Because of confidence in the inevitable spread of slavery, the average sale price of a slave in the bustling New Orleans human-trafficking market rose 21 percent within one year of President John Tyler’s decision to annex Texas (during his final days in office) in 1845. According to international law, Texas remained Mexican. Tyler’s decision alone was tantamount to a declaration of war. Still, for at least a year, the Mexicans showed restraint and unhappily accepted the de facto facts on the ground. American Blood Upon American Soil?: The Specious Case for War It took an even greater provocation to kick off a major interstate war between America and Mexico. And that provocation indeed came. In 1844, in one of the more consequential elections in U.S. history, a Jackson loyalist (nicknamed “Young Hickory”) and slaveholder, James K. Polk, defeated the indefatigable Whig candidate Henry Clay. Clay preferred restraint with respect to Texas and Mexico; he wished instead to improve the already vast interior of the existing United States as part of his famed “American System.” Unfortunately for the Mexicans, Clay was defeated, and the fervently expansionist Polk took office in 1845. His election demonstrates the contingency of history; for if Clay had won, war might have been avoided, slavery kept from spreading in the Southwest, and America spared a civil war. It was not to be. Just before Polk took office, a dying Andrew Jackson provided him the sage advice that would spark a bloody war: “Obtain it [Texas] the United States must, peaceably if we can, but forcibly if we must.”

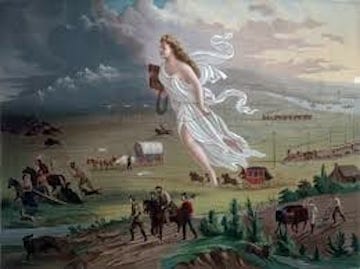

In the end, it was Polk who would order U.S. troops south of the disputed Texas border and spark a war. Still, the explanation for war was bigger than any one incident. A newspaperman of the time summarized the millenarian scene of fate pulling Americans westward into the lands of Mexicans and Indians. John L. O’Sullivan wrote, “It has become the United States’ manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” There was an American sense of mission, clear from the very founding of Puritan Massachusetts, to multiply and inhabit North America from ocean to ocean. Mexico and the few remaining native territories were all that stood in the way of American destiny by 1846. As the historian Daniel Walker Howe has written, “ ‘Manifest Destiny’ served as both label and a justification for policies that might otherwise simply been called … imperialism.” Polk was, at least in terms of accomplishing what he set out to do, one of the most successful presidents in U.S. history. He declared that his administration had “four great measures.” Two involved expansion: “the settlement of the Oregon territory with Britain, and the acquisition of California and a large district on the coast.” Within three years he would have both and more. Interestingly, though, Polk wielded different tactics for each acquisition. First, Oregon: Britain and the U.S. had agreed to jointly rule this territory, which at that time reached north to the border with Alaska. Expansionist Democrats who coveted the whole of Oregon ran on the party slogan “54°40′ or Fight!” (a reference to the latitude at the top of the Oregon of that day, a line that marks today’s southern border of the state of Alaska). In the end, however, Polk would not fight Great Britain for Canada. Instead, he compromised, setting the modern boundary between Washington state and British Columbia. In his dealings with the much less powerful Mexicans, however, Polk took an entirely different, more openly bellicose approach. Here, it seems, he expected if not preferred a war. Was his compromise in Oregon reflective of great-power politics (Britain remained a formidable opponent, especially at sea) or tainted by race and white supremacist notions about the weakness of Hispanic civilization? Historians still argue the point. What we can say is that many Democratic supporters of Polk delighted over the Oregon Compromise, for, as one newspaper declared: “We can now thrash Mexico into decency at our leisure.” War it would be. In the spring of 1846, President Polk sent Gen. Zachary Taylor and 4,000 troops along the border between Texas and Mexico. Polk claimed all territory north of the Rio Grande River despite the fact that the Mexican province had always established Texas’ border further north at the Nueces River. Polk wanted Taylor to secure the southerly of the two disputed boundaries—probably in contravention of established international law. No one should have been surprised, then, when in April a reconnaissance party of U.S. dragoons was attacked by Mexican soldiers south of the Nueces River. Polk, of course, wily politician that he was, acted absolutely shocked upon hearing the news and immediately began drafting a war message—even though, in fact, his administration had been on the verge of asking Congress for a war declaration anyway! In the exact inverse of his negotiations with Britain over Oregon, Polk had made demands (that Mexico sell California and recognize Texan independence) he knew would probably be rejected by Mexico City, and then sent soldiers where he knew they would probably provoke war. And, oh, how well it worked. Indeed, Polk’s administration had already set plans in motion for naval and land forces to immediately converge on California and New Mexico when the outbreak of war occurred. Both the U.S. Army and Navy complied and within a year occupied both Mexican provinces. Lest the reader believe the local Hispanics were indifferent to the invasion, homegrown rebellions broke out (and were swiftly suppressed) in both locales. Polk got his war declaration soon after the fight in south Texas. In a blatant obfuscation, Polk announced to the American people that “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon American soil. War exists, and notwithstanding all our efforts to avoid it, exists by the act of Mexico herself.” He knew this to be false. So did many Whigs in the opposition party, by the way. Still, most obediently voted for war, fearing the hypernationalism of their constituents and remembering the drubbing Federalists had taken for opposing the War of 1812. In cowardly votes of 174-14 in the House (John Quincy Adams, the former president, was one notable dissenting vote) and 40-2 in the Senate, the Congress succumbed to war fever. The small skirmish near the Nueces River was just a casus belli for Polk; America truly went to war to seize, at the very least, all of northern Mexico. Gen. Winfield Scott and the Defeat of Mexico On the surface, the two sides in the Mexican-American War were unevenly matched. The U.S. population of 17 million citizens and 3 million slaves dwarfed the 7 million Mexicans (4 million of whom were Indians). Their respective economies were even more lopsided, for America had emerged strong from its market and communications revolutions. Mexico had only recently (1821) gained its independence, and its political situation was fragile and fluctuating. The U.S. had existed independently for some 60 years and already had fought two wars with Britain and countless battles with Indian tribes. America was ready to flex its muscles. Many observers assumed the war would be easy and short. It was not to be. Most Americans underestimated the courage, resolve and nationalism of Mexican soldiers and civilians alike. That the U.S. won this war—and most of the battles—was due primarily to superiority in artillery, leadership and logistics. The U.S. Military Academy at West Point in New York had trained, and numerous Indian wars had seasoned, a generation of junior and mid-grade officers. Many of the lieutenants and captains who directly led U.S. Army formations in Mexico (one thinks of Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman and James Longstreet, to name only a handful) would serve, either for the North or the South, as general officers in the U.S. Civil War (1861-65). Some of these officers involved in the Mexican-American War relished the glory of exotic conquest; others were horrified by a war they deemed immoral. It must be remembered that the U.S. Army that entered and conquered Mexico represented a slaveholding republic fighting against an abolitionist nation-state. Many Southern officers brought along slaves and servants on the quest to spread “liberty” to the Mexicans. Some of the enslaved took the opportunity to escape into the interior of a non-slaveholding country. The irony was astounding. President Polk’s Army was also highly politicized during the conflict. While the existing regular Army officers tended to be Whigs (in favor, as they were, of internal improvements and centralized finance to the benefit of the military), all 13 generals that Polk appointed were avowed partisan Democrats. Polk’s biggest fear—which would indeed come to fruition in the election of Gen. Zachary Taylor as president in 1848—was that a Whiggish hero from the war he began would best his party for the presidency. When it became clear in 1846 that Gen. Taylor’s initial thrust south into the vast Mexican hinterland could win battles but not the war, Gen. Winfield Scott (a hero of the War of 1812) was ordered to lead an amphibious thrust at the Mexican capital. Indeed, Scott’s militarily brilliant operational campaign constituted the largest American seaborne invasion until D-Day in World War II. It took months of hard fighting and several more months of tenuous occupation, but Scott’s attack effectively ended the war by late 1847. Still, conducting this war was extremely hard, indeed more difficult than it should have been, on both Taylor and Scott. This was due to President Polk’s decision (reminiscent of George W. Bush’s decision during the Iraq War) to cut taxes and wage war simultaneously. Indeed, Gen. Scott became so short on troops and supplies that he decided to cut off his line of logistics and “live off the land.” This was a clever but risky maneuver that his subordinates—U.S. Grant and William T. Sherman—would remember and mimic in the U.S. Civil War. There was plenty of room for courage and glory on both sides of the Mexican-American War. It is no accident that the contemporary U.S. Marine Corps Hymn speaks of the “Halls of Montezuma,” or that several grandiose rock carvings of key battle names in Mexico unapologetically adorn my own alma mater at West Point. On the other side, the Mexican people still celebrate the gallant defense, and deaths, of six cadets—known as Los Niños Héroes—who manned the barricades of their own national military academy. Nevertheless there was (and always is) an uglier, less romantic side of the conflagration. Nine thousand two hundred seven men deserted the U.S. Army in Mexico, or some 8.3 percent of all troops—the highest ever rate in an American conflict and double that of the Vietnam War. Hundreds of Catholic Irish immigrant soldiers responded to Mexican invitations and not only deserted the U.S. Army but joined the Mexican army, as the San Patricio (Saint Patrick’s) Battalion. Dozens were later captured and hanged by their former comrades. America’s military also waged a violent, brutal war that often failed to spare the innocent. In northern Mexico, Gen. Taylor’s artillery pounded the city of Matamoros, killing hundreds of civilians. Indeed, Taylor’s army of mostly volunteers regularly pillaged villages, murdering Mexican citizens for either retaliation or sport. Many regular Army officers decried the behavior of these volunteers, and one officer wrote, “The majority of the volunteers sent here are a disgrace to the nation; think of one of them shooting a woman while washing on the banks of the river—merely to test his rifle; another tore forcibly from a Mexican woman the rings from her ears.” In the later bombardment of Veracruz, American mortar fire inflicted on the elderly, women or children two-thirds of the 1,000 Mexican casualties. Capt. Robert E. Lee (who would later lead the Confederate Army in the U.S. Civil War) was horrified, commenting that “my heart bled for the inhabitants, it was terrible to think of the women and children.” It should come as little surprise, then, that when the U.S. Army seized cities, groups of Mexican guerrilla fighters—usually called rancheros—often rose in rebellion. Part of the U.S. effort in Mexico became a counterinsurgency. Take my word for it, people (Iraqis, for example) rarely take kindly to occupation, and the mere presence of foreigners often generates insurgents. All told, the American victory cost the U.S. Army 12,518 lives (seven-eighths of the deaths because of disease, due largely to poor sanitation). Many thousands more Mexican troops and civilians died. This aspect of the war, events that tarnish glorious imagery and language, is rarely remembered, but it would be well if it were. Courageous Dissent: Whigs, Artists, Soldiers and the Opposition to the Mexican-American War War, as it does, initially united the country in a spirit of nationalism, but ultimately the war and its spoils would divide the U.S., nearly to its breaking point. Few mainstream Whigs—those of the opposition party—initially demonstrated the courage to dissent. They knew, deep down, that this war was wrong, but also remembered the fate of the Federalist Party, which had been labeled treasonous and soon disappeared due to its opposition to the War of 1812. Other Whigs were simply dedicated nationalists: The U.S. was their country, right or wrong. But there were courageous voices, a few dissenters in the wilderness. Some you know; others are anonymous, lost to history. All were patriots. Many were politicians: those entrusted with the duty to dissent in times of national error. Though only a dozen or so Whigs had the fortitude to vote against the war declaration in 1846, a few were vocal. One was Rep. Luther Severance, who responded to President Polk’s “American blood on American soil” fallacy by exclaiming that “[i]t is on Mexican soil that blood has been shed” and Mexicans “should be honored and applauded” for their “manly resistance.” Another was former President John Quincy Adams, who at the time was a member of the U.S. House from Massachusetts (he was the only person to serve in Congress after being president). It was Adams, we must remember, who as secretary of state in 1821, had presciently warned Americans against foreign military adventures. “But she [America] goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” he wrote, for “[Were she to do so] the fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force … she might become the dictatress of the world.” Adams had seen the Mexican War coming back in 1836, when his avowed opponent President Andrew Jackson considered annexation of the Texan Republic. Then, Adams had said, “Are you not large and unwieldy enough already? Have you not Indians enough to expel from the land of their fathers’ sepulchre?” Another staunch opponent of the war was a little known freshman Whig congressman from Illinois, a lanky fellow named Abraham Lincoln. As soon as he took his seat in the House, Lincoln immediately rebuked President Polk’s initial explanation for declaring war. “The President, in his first war message of May 1846,” Lincoln told his audience, “declares that the soil was ours on which hostilities were commenced by Mexico; Now I propose to try to show, that the whole of this–issue and evidence–is, from beginning to end, the sheerest deception.” The future president would later summarize the conflict as “a war of conquest fought to catch votes.” And, indeed it was. Prominent artists and writers also opposed the war; such people often do, and we should take notice of them. The Transcendentalist writers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson each took up the pen to attack the still quite popular conquest of Mexico. Thoreau, who served prison time, turned a lecture into an essay now known as “Civil Disobedience.” Emerson was even more succinct, declaring, “The United States will conquer Mexico, but it will be as a man who swallowed the arsenic which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us.” He couldn’t have known how right he was; arguments over the expansion of slavery in the lands seized from Mexico would indeed take the nation to the brink of civil war in just a dozen years. One expects dissent from artists. These men and women tend to be unflinching and to demonstrate a willingness to stand against the grain, against even the populist passions of an inflamed citizenry. But … soldiers? Surely they must remain loyal and steadfast to the end, and so, too often, they are. Not so in Mexico. A surprising number of young officers—like Lee at the bombardment of Veracruz—despised the war. More than a few likely suffered from what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One lieutenant colonel, Ethan Hitchcock, even attacked the justification for war. He wrote, “We have not one particle of right to be here. It looks as if the [U.S.] government sent a small force on purpose to bring on a war, so as to have the pretext for taking California and as much of this country as it chooses.” Perhaps the most honest and self-effacing critique of the war came from a young subaltern named U.S. Grant (who along with his then-comrade R.E. Lee would later lead one of the two opposing armies in the Civil War). Grant, a future president and West Point graduate, wrote that he “had a horror of the Mexican War … only I had not the moral courage enough to resign.” Finally, let us return to the powerful and unwavering dissent of John Quincy Adams, for the Mexican War, not his presidency, may constitute his finest hour. On Feb. 21, 1848, the speaker of the House called for a routine vote to bestow medals and adulation on the victorious generals of the late Mexican War. The measure passed, of course, but when the “nays” were up for roll call a voice from the back bellowed “No!” It was the 80-year-old former president. Adams then rose in an apparent effort to speak, but his face reddened and he collapsed. Carried to a couch, he slipped into unconsciousness and died two days later. John Quincy Adams was mortally stricken in the act of officially opposing an unjust war. That we remember the victories of the Mexican-American War but not Adams’ dying gesture surely must reflect poorly on us and our collective remembrances. A Long Shadow Cast: The ‘Peace’ of 1848 From the war’s start, there was never any real question of leaving Mexico without extracting territory. Indeed, by late 1847 there was considerable Democratic support for taking the whole country. That the U.S. did not is due mainly to Polk’s peace commissioner ignoring orders and his own firing to negotiate a compromise. But there was something else. Many Democrats from the South—who had applauded the war from the start—now flinched before the prospect of taking on the entirety of Mexico and its decidedly brown and Catholic population. There was inherent fear of racial mixing, racial impurity and heterogeneity. John Calhoun, the political stalwart from South Carolina, even declared, “Ours is the government of the white man!” And, in 1848, Calhoun was right, indeed. Even the Wilmot Proviso, an attempt by a Northern congressman to forestall any conquest in Mexico, was tinged with racism. Rep. David Wilmot called his amendment a “White Man’s Proviso,” to “preserve for free white labor a fair country, a rich inheritance, where the sons of toil, of my own race and own color, can live without the disgrace which association with Negro slavery brings upon free labor.” Wilmot’s proposal, unsurprisingly, never passed muster. But it nearly tore the Congress asunder, with Northern and Southern politicians at each other’s throats. Northerners generally feared the expansion of slave states and of what they called “slave power.” The Whig Party itself nearly divided—and eventually would—into its Northern and Southern factions. As we will see, arguments about what land to seize from Mexico and what to do with it (should it be slave or free?) would shatter the Second Party System—of Whigs and Democrats—and take the nation one step closer to the civil war many (like John Quincy Adams) had long feared. The “peace” of 1848, known to history as the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo, would certainly cast a long shadow. * * * In the end, the U.S. expended over 12,000 lives and millions of dollars to make a new colony of nearly half of Mexico—an area two and a half times the size of France and including parts or all of the current states of California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. Much of the land remained heavily Hispanic for decades and effectively under military government for many years (New Mexico until 1912!). The real losers were the Indian and Hispanic people of the new American Southwest. The U.S. gained 100,000 Spanish-speaking inhabitants after the treaty and even more native Americans. Under Mexican law, both groups were considered full citizens! Under American stewardship, race was a far more detrimental factor. The results were (despite supposed protections in the treaty) the seizure of millions of acres of Hispanic-owned land and, in California, Indian slavery and decimation as 150,000 natives dwindled to less than 50,000 in just 10 years of U.S. control. During the postwar period, California’s governor literally called for the “extermination” of the state’s Indians. This aspect of the war’s end is almost never mentioned at all. Words matter, and we must watch our use of terms and language. Mexico hadn’t invaded Texas; Texas was Mexico. Polk manufactured a war to expand slavery westward and increase pro-slavery political power in the Senate. Was, then, America an empire in 1848? Is it today? And why does the very term “empire” make us so uncomfortable? So what, then, are readers to make of this mostly forgotten war? Perhaps this much: It was as unnecessary as it was unjust. Nearly all Democrats supported it, and most Whigs simply acquiesced. Others, however, knew the war to be wrong and said so at the time. Through an ethical lens, the real heroes of the Mexican-American War weren’t Gens. Taylor and Scott, but rather artists such as Henry David Thoreau; a former president, John Quincy Adams; and Abraham Lincoln, then an obscure young Illinois politician. There are many kinds of courage, and the physical sort shouldn’t necessarily predominate. In this view, the moral view, protest is patriotic. So, let me challenge you to think on this: Our democracy was undoubtedly achieved through undemocratic means—through conquest and colonization. Mexicans were just some of the victims, and, today, in the American Southwest, tens of millions of U.S. citizens reside, in point of fact, upon occupied territory. * * * To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

Source URL |