| Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”? Below is the twentieth installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. * * *

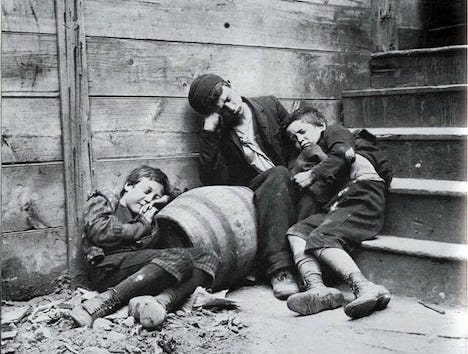

The Gilded Age. The American Industrial Revolution. The Progressive Era. Call it what you will, but one salient (Dickensian) fact about this period endures: It was the best of times, it was worst of times—depending on one’s point of view. Industrialization brought immense wealth for some and crippling poverty for others. Mass production might result in savings for the consumer, but working wages remained low. The boom-and-bust cycle of laissez-faire capitalism was in full swing, resulting in national banking panics and, from 1893 to 1897, the worst financial depression up to that point in the country’s history. The key story of this era revolves around various attempts—by rural farmers and urban workers, by women and blacks, Republicans and Democrats, Populists, Progressives and even socialists—to mitigate the excesses of industrialized American capitalism. It would not prove to be an easy task, and, one could cogently argue, it is a task Americans still grapple with. The two-party system nearly fell apart in this period because neither major political brand seemed to have a viable answer to the key question of day: how to maintain peace and the basic standard of living during a time of massive industrial growth and rising economic inequality. It is a question familiar to supporters of Donald Trump and supporters of Bernie Sanders. Were the corporate leaders of the Gilded Age corrupt “robber barons” or “rags-to-riches” heroes? Was factory work a long-term good, driving down prices and growing the American economy, or was it soul-sucking wage slavery? Maybe both. What’s certain is that the nature of labor changed forever. Systems of efficiency like “Taylorism” and the assembly line specialized labor and brought much monotony to the workplace. Early American factory life was a nightmare, not unlike contemporary conditions in much of the developing world. The tyranny of the clock (a relatively new addition to the factory floor) dominated life as the average laborer worked six days a week, 10 hours a day. By 1900, there were 1.7 million children toiling in the labor force. Worse still, in the late 19th century neither political party supported unions or any sort of modern social welfare system or safety net. The results were barbaric. Unorganized workers lacked health care, safety regulations and unemployment insurance. From 1880 to 1900, there were 35,000 deaths on the job, annually—the equivalent of a Korean War every year for two decades. Beyond the fatalities, an average of 536,000 men and women were injured at work in each of those years. The coldhearted ideology of the day—in both major political parties and among the wealthy—tended to blame poverty on the workers themselves. Except among a tiny (but growing) core of socialists, few Americans who were not directly affected by the plight of workers demonstrated any enthusiasm for federal intervention or poverty mitigation. Indeed, the Democratic President Grover Cleveland—a fiscal conservative—declared in 1893, “While the people patriotically and cheerfully support their Government, its functions do not include the support of the people.” The Republicans were often even less sympathetic. Most politicians simply reflected the prevailing mores. American elites (and many hoodwinked workers and farmers) clung tightly to belief in the American Dream—that with enough hard work and grit anyone, by pulling on one’s own bootstraps, could become rich. The empirical statistics, even then, debunked this ideology as little more than anecdotal, but it endured and endures. An academic of that era, William Sumner, summarized this viewpoint: “Let every man be sober, industrious, prudent, and wise and poverty will be abolished in a few generations.” Nor did many popular preachers, such as Henry Ward Beecher, show much sympathy for the plight of the poor, with Beecher famously announcing that “[n]o man in this land suffers from poverty unless it be more than his fault—unless it be his sin.” Nonetheless, when the economy finally collapsed in 1893—due in large part to the corruption and excesses of various corporate monopolies—setting off the worst depression in U.S. history to that point, views on charity, social welfare and the supposed character defects of the poor began to change. Perhaps the federal and local governments did have a role in citizens’ welfare. Of this much, many were sure: Something had to change.

Populism and Agrarian Revolt: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly After 1877, when the Republican Party abandoned Southern blacks along with any remnants of its old abolitionist sentiment, the GOP became increasingly identified as the party of “business,” of corporations and the capitalist class. The Democrats, now largely a regional (Southern) party, also proved initially conservative on economic issues and stuck with pure free-market capitalism. Neither party, it seemed, appealed to the best interests of small rural farmers or urban wage workers. One result of industrialization was the accumulation of massive wealth in the hands of the very few (mostly Northern and Eastern corporatists). In 1890, the richest 1 percent of the population owned 51 percent of the national wealth, while the poorest 44 percent owned less than 2 percent of the wealth. The result of this imbalance was instability, strikes, work stoppages, federal intervention and, often, bloodshed. Unions formed, shattered and rose again. Still, at a national level, it was the rural farmers who first revolted. Farmers felt themselves the perennial victims of a rigged system. They lived by the whims of market prices, of supply and demand. They hated the national tariff—which “protected” urban manufacturing but caused rising costs in the consumer goods necessary to live on the prairie. Furthermore, the post-Civic War move away from paper currency (or “greenbacks”) to hard specie, meaning gold, devastated all but the wealthiest farmers. Seeing themselves as the ideal Americans of the Jeffersonian vision—the salt of the earth who tilled the land—they demanded that silver (which was more plentiful) as well as gold be used to back their paper currency. Small farmers simply didn’t have much in the way of gold reserves, and the “hard money” policies of the Republicans and urban elites devalued what little cash they had. Disgusted with two-party politics, and feeling abandoned by both mainstream Republicans and Democrats, a new organization, the People’s Party, formed and met with early electoral successes in their Western and (sometimes) Southern heartlands. The Populists, as they were called, entered American politics and, in one guise or another, have been with us ever since. Theirs was the policy and ideology of “us” versus “them,” rich versus poor, West versus East, rural versus urban and—lamentably—white versus black. The Populists for the most part distrusted the state; then again, they did support federal intervention when it suited them. Riding a tidal wave of rural and agricultural support, by 1896 William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska managed a veritable takeover of the Democratic Party, fusing it with the Populists, and ran for president. Bryan was one the great orators in American history. His speeches summoned the tone of evangelical church rallies. At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Bryan mesmerized the crowd as he placed an imaginary crown of thorns on his head and pronounced, “We will answer their [the Republicans] demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns.” Then, stretching out his arms as if on a cross, he hollered, “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” Bryan, however popular and however enthralling on a podium, would go on to lose in 1896 (and then twice more). He was defeated by the Republican William McKinley, who ran on a platform of nationalism and status quo “prosperity” and who labeled Bryan a radical tainted by his party’s association with the old Confederate South. And there was something else: money in politics. McKinley and his corporate Republicans raised $7 million (the equivalent of $3 billion today), the Democrats just $300,000. Bryan ran an energetic campaign, riding the rails and giving 600 speeches in 27 states; McKinley rarely left his home and rested on his financial advantages. In the end, money won. McKinley would be president. Lest we become too sentimental and consider Bryan’s and the Populists’ failed campaign as some sort of moral victory, it is necessary to illuminate the “dark side” of Populism. Many Populists demonstrated strong strains of nativism and racism. They railed against “Jew” bankers, “Slavic” immigrants up north and, in the South, the “Negro menace.” This was not mere rhetoric. As Populism rose in the West and South, blacks were being utterly disenfranchised. Southern states—now back in the hands of many former Confederate leaders—struck almost every eligible black voter from the rolls. Between 1898 and 1910, the number of black registered voters in Louisiana dropped from 130,000 to 730! Populism, in other words, may have been the party of the “people,” but it was most certainly only thus for white people. Consider the contrast. The very year Bryan ran his crusading campaign (1896), the Supreme Court would hold that segregation was legal when it ruled in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Few Populists made an effort to craft an interracial alliance of poor people, and thus it was ultimately American blacks who were left to writhe on Bryan’s proverbial cross of gold. The Progressive Moment: Social Freedom or Social Control The Panic and Depression of 1893 was so severe—and the government so unprepared and unwilling to intervene—that millions of families were brought to the brink of starvation, and the “ranks of a tramp army” (of unemployed men) swelled. Though the Populists never managed to convince or co-opt Northern factory workers to join their crusade, many of the sentiments and proposed policies of the People’s Party began to infuse a new movement of (mostly middle class) “Progressives,” as they styled themselves. Progressives weren’t exactly radical in the traditional sense—though their wealthy opponents depicted them as such—and they belonged to both major political parties. What they most had in common was an abiding criticism of the excesses of American “boom-bust” capitalism, and a sense that regulation of markets and the intervention of government could mitigate the worst aspects of this and future depressions. Throughout their heyday, 1896-1920 or so, Progressives called for, and often achieved, many of the government programs and policies that exist to this day. They pushed for antitrust and anti-monopoly regulations, the eight-hour workday, an end to child labor and unemployment, and workers’ compensation insurance, to name but a few. One problem for the Progressives was their inability to forge lasting alliances with rural Populists, whom they saw as backward country bumpkins. Nor did the rural poor trust the machinations of these urban (seemingly arrogant) reformist Progressives. The two groups had such divergent cultural values and traditions—as well as different views on immigration and government intervention—that a true union of urban/rural workers and reformists never manifested itself. Historians long have argued about the ultimate nature of the Progressive movement. Some view the Progressives as genuine reformers with the best interest and freedoms of the working classes at their root. Others sense an overriding aura of social control in the Progressive agenda. Though the remarkable achievements of the Progressives should never be ignored, their paternalist and controlling side bears some analysis. As true believers in the government’s ability to reform, regulate and solve the nation’s economic and social problems, Progressives sometimes displaced the social justice rhetoric of the Populists “with slogans of efficiency.” Indeed, Progressives seemed to “know what was best” for poor farmers and urban immigrants alike—sobriety and moderation. This explains why so many Progressives were also in favor of temperance. Their motto was “trust us,” meaning the experts, your social and educational betters. While Populism pitted the “people” against the state, Progressives believed in the utility of using (through new theories of social science) the state to intervene in the economy and reform society. Indeed, the paternalistic impulses of some Progressives were such that they saw the masses—urban or rural—as a threat to democracy, a populace itself in need of regulation. Therein lies part of the “dark side” of the Progressive movement. Sure, Progressives made great, if gradualist, progress on improving working conditions, government regulation and the right of (white) women to vote. This ought to be rightfully celebrated. Still, many Progressives, both academics and policymakers, believed in the social Darwinist notion of human beings’ “survival of the fittest.” In that vein, a powerful wing of the Progressives backed eugenics programs of forced sterilization laws. Those deemed physically or mentally unfit were to be sterilized for the good of the American “whole.” Beginning in 1907, two-thirds of U.S. states would eventually pass forced-sterilization laws. Indeed, even the Supreme Court ruled, in Buck v. Bell (1927), that compulsory sterilization was fully legal and constitutional. In a disturbing irony, Adolf Hitler and other Nazis would later cite America as a positive example and model of their early racial purity programs. Progressives had a deep blind spot related to race in general and African-Americans in particular. The inconvenient fact is that the “Progressive Era” coincided with the Jim Crow era and the height of racial terrorism in the South. When Progressives talked about easing inequality they meant white inequality. The same went for most Populists. Indeed, as The New York Times reported on the 1924 Democratic National Convention: “An effort to incorporate in the Democratic Platform a plank condemning the Ku Klux Klan … was lost early this morning by a single vote. … There [was oratory against the proposal] by William Jennings Bryan, who spoke with his old-time fire and enthusiasm.” “Progressive” Democrats couldn’t even agree to condemn the Klan! Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. The Progressives and Populists had one thing in common: They wanted to win national elections. As a result, they showed a willingness to play the race card and ignore the Southern regime of terror that was then at its height. As most Progressives and Populists remained silent, lynching reached its zenith in this era, and neither party took national action. It didn’t take very much for a black man to be lynched in the “Progressive Era” South. In 1889, Keith Bowen was killed for simply entering a room where three white women were sitting. In 1904, a white mob lynched a black man for knocking on a white woman’s door. In 1912, Thomas Miles was killed for writing a note to a white woman, inviting her for a cold drink. Multiply this by a thousand and one gets a sense of the scale of lynching in this period. And what did a self-described “Progressive” president, Theodore Roosevelt, have to say about all of this? The New York-bred Brahmin lowered himself to the baseness of a Southern apologist. He stated that “the greatest existing cause of lynching is the perpetration, especially by black men, of the hideous crime of rape.” How’s that for victim blaming? The Wild Election of 1912: Who Was the Real Progressive? Nevertheless, by 1912 the old notion of a governmental hands-off policy in economics and society was out of style. In that presidential election, three men ran on a platform of “Progressivism”—Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, Democratic challenger Woodrow Wilson and the old stalwart Theodore Roosevelt, who had formed his own third-party, the Progressive (or “Bull Moose”) Party. In this election, the three main candidates all sought to “out-progressive” the others. In truth, though, the men were, in their policies and platforms, remarkably similar. And they admitted it! Wilson, the Democrat, stated, “When I sit down and compare my views with those of a Progressive Republican I can’t see what the difference is.” Roosevelt, ever more succinct and blunt, declared that “Wilson is merely a less virile me.” So who was most traditionally Progressive? It’s a tough question. Roosevelt was most associated with Progressivism, in theory. He touted his achievements as a “trust-buster,” believed that big government could balance big business, and had a strong environmental record (including an expanded program of national parks). Still, he was socially conservative, feared “anarchy” and supported overt imperialism. His racism, and that of his followers, was also a problem—some called the Roosevelt wing of the Republican Party the “Lily-whites.” Taft, though portrayed by his opponents as a “business” Republican, actually busted twice the number of trusts as Teddy, mandated an eight-hour workday for federal employees and pushed for a progressive income tax. Wilson—born to a slaveholding family in Virginia in 1856—had racist instincts but supported some trust-busting and believed the Constitution to be a “living document” that must change with the times. In the end, Roosevelt (though the most successful third-party candidate in history) split the Republican vote and propelled Wilson into the White House. Wilson followed through on many of his campaign promises, and the 63rd Congress, during his first term as president, was one of the more productive in U.S. history. Under Wilson’s watch, Congress lowered the tariff, abolished child labor and passed a new antitrust act, the eight-hour workday and federal aid to farmers. Wilson’s first term seemed a Progressive dream. But the man also had Southern roots and was a product of his era and its hateful culture. The favorite movie of the Progressive Wilson was “The Birth of a Nation,” which depicted the KKK as heroic. Furthermore, he excluded black soldiers from the 50th-anniversary observance of the Battle of Gettysburg and ushered in segregation of federal buildings and the federal civil service. On the issue of race, under Wilson, “Progressive America” had took a step backward.

Why No Socialism in America?: Urban, Rural and Racial Division The hopes and fears of the period are captured in “The Strike,” an 1886 painting by Roger Koehler. In it, a crowd of workers approaches the home of a well-dressed factory owner. Amid the tension, a man picks up a stone. It is a question asked time and again by historians on both sides of the Atlantic: Why did a significant socialist movement not rise in the United States as it did in Europe? Indeed, one could argue that this is one of the rare things that actually is “exceptional” about America. Indeed, while many liberal Progressives in the U.S. admired the social programs long flourishing in industrialized Europe, they never managed to implement most of these policies in Washington. One reason they had so much trouble was the power of the courts in America. Through the peculiar U.S. system of lifetime appointments of judges, the justices—especially on the Supreme Court—were a generation behind contemporary policymakers and tended to strike down social welfare provisions as unconstitutional. It would take decades to modernize the court. European countries rarely had such problems with experimentation and improvisation. Thus, the United States fell way behind Europe on social welfare (and remains so today). One dream of American Progressives was universal health insurance, which they proposed back in 1912. More than a century later, the U.S. holds the distinction of being perhaps the last major industrialized country not to have such a program. Germany had shown the way in 1883, and the United Kingdom passed the National Insurance Act in 1911. This is not to say that American socialists did not exist. In fact, 1912 was probably the high tide of socialist sentiment in this country. Many socialists, including their party leader, Eugene Debs, a former union man, believed that neither of the two major parties had an answer to the ills and excesses of capitalism. As one union member summed it up, “People got mighty sick of voting for Republicans and Democrats when it was a ‘heads I win, tails you lose’ proposition.” Though it is rarely remembered or spoken of now, in 1911 card-carrying Socialists were elected mayors of 18 cities, and more than 300 held office in 30 states. In the 1912 presidential election, Debs received a remarkable 1 million votes, the most ever for a far-left socialist candidate. Clearly, some proportion of voters agreed with Debs that “[t]he Republican and Democratic parties, or, to be more exact, the Republican-Democratic party, represent the capitalist class in the struggle. They are the political wings of the capitalist system.” Still, though Debs’ accomplishments were real, it must be said that no serious socialist or social democratic movement ever gathered much steam on this side of the Atlantic. The reasons were as numerous as they were lamentable. The working class in the United States was utterly divided against itself—something the owners of this country exploited and perpetuated. Rural Populists wanted lower tariffs, cultural homogeneity, an end to new immigration, and a return to “traditional values.” They were never able to make common cause with the urban (often immigrant) working class, despite their obvious common interests. Just as today, the American working and middle classes were waging a culture war over race, citizenship, immigration and social “values.” But the main factor was race, specifically the “Negro question.” Both urban white immigrants and rural white farmers defined progress and reform along the narrowest of racial contours. They believed in white Progressivism and white Populism. In the interest of not alienating their parties’ Southern wings and winning elections and because of their downright bigotry, they left African-Americans to suffer economic peonage and physical torment. Progressives and Populists of the period failed to recognize one salient truth: Some cannot be free so long as all are not free. When it came to fulfilling the idealistic dreams of populism and progressivism, race, as in so many American matters, would prove to be the nation’s Achilles’ heel. It would take two generations to even begin to right that wrong. * * * To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

Source URL |