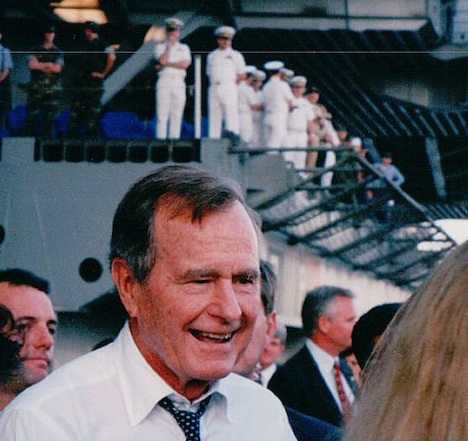

Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”? Below is the thirty-fourth installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. * * * His vice president was everything Ronald Reagan was not. The Hollywood actor in chief had far less political qualification “on paper” than his 1980 Republican primary opponent, George H.W. Bush. Though Reagan oozed optimism and soothed the American people with his confident, digestible rhetoric, he was certainly no policy expert or Washington insider. Bush was both. He was a man born of privilege, scion of a prestigious, wealthy family and son of a Republican U.S. senator from Connecticut, Prescott Bush. However, the mid-20th century was different from our own time; it was an era when affluence and social standing didn’t obviate a sense of duty to country and family honor. Bush, like so many thousands of the other members of the American aristocracy, volunteered for the U.S. military in response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Not yet 19, he would become the youngest pilot in the U.S. Navy at that time, eventually flying dozens of combat missions in the Pacific theater. In September 1944 he was involved in an action that won him the Distinguished Flying Cross. In the words of the citation, “Bush pressed home an attack in the face of intense antiaircraft fire. Although his plane was hit and set afire at the beginning of his dive, he continued his plunge toward the target and succeeded in scoring damaging bomb hits before bailing out of the craft.” He was the only member of the three-man crew to live through the incident. Afterward, survivor’s guilt bled through his letters home. At war’s end Bush entered Yale. After moving to Texas and finding wealth and respect in the oil industry, he followed his father into politics. He won a House seat in the 1960s, then lost a race for the U.S. Senate (he was unable to shake his Eastern establishment image with Texas voters, try as he might). In the 1970s, he was appointed ambassador to the United Nations, director of the Central Intelligence Agency and head of the Republican National Committee (RNC). After Bush’s 1980 defeat in a rather bitter presidential primary battle with Reagan—in which the Texan declared that his opponent, a “supply-side theory” advocate, was proposing “voodoo economics”—the Gipper chose Bush as his running mate. They stood together at the helm of the executive branch for eight years, though Bush tended to work behind the scenes, overshadowed by Reagan’s big personality. Though no doubt a conservative, Bush harkened back to the yesteryears of Northeastern centrist, “country club” Republicanism. By 1980, and especially by the time of his successful 1988 run for the presidency, Bush’s credentials and tone made him an anachronism in a party vaulting rightward and increasingly in the grip of Southern whites and evangelical Christians who focused on social and cultural values. Bush tried to fit into the mold that his political base required, but he was always a fish out of water. His entire time as vice president and president, from 1981 to 1993, was, in a sense, defined by his battles with the increasingly dominant right wing of his party. Bush was hardly less conservative, for the most part, than Reagan, but the earlier president, with his soaring rhetoric, charm and (usually unfulfilled) promises, was more successful in holding the Republican coalition together. Bush never really found the knack for it. It probably cost him a second term. Although George H.W. Bush can be viewed as perhaps the last of the (relatively) centrist Republican presidents, he was no friend to liberals. As president, his domestic policies were rather comparable to Reagan’s, and, at least on the domestic front, he was never much of a bipartisan coalition builder. He sought, just as his predecessor had, to destroy what remained of the liberal consensus. As a result, the opposition party moved rightward, and increasingly conservative “New Democrats”—including one Bill Clinton—would emerge and ultimately defeat him. He was stronger on foreign policy, where he was relatively cautious and methodical in his approach, than on domestic policy. Nonetheless, he was an avowed interventionist and threw U.S. troops into some unnecessary adventures. After his death in the second decade of the 21st century, he was canonized by nostalgic Democrats and Republicans alike. Some dubbed him “the best one-term president” in U.S. history. This was an overstatement, undoubtedly, but one can understand the sentiment. Looking back at his presidency from 30 years on, Bush 41 does appear to be a moderate and decent leader and a gentleman. Still, a close look at the actual substance of his administration complicates this image and deflates many of its myths. Decent Man, Nasty Campaign: The Election of 1988 Bush may have had a high-bred pedigree and a gentile image seemingly from an earlier era, but he was undoubtedly highly ambitious and willing to practice hard-nosed, even harsh politics. He knew he would have to tack right in the 1988 Republican primaries to best his two insurgent opponents, Sen. Bob Dole of Kansas and Pat Robertson, the Christian televangelist. The race seemed tight at first, but Bush, as Reagan’s anointed successor, won the day. At the Republican National Convention, Bush sought to balance his personal moderation with the increasingly right-wing penchant of his base. He delivered an acceptance speech that at times sounded Reaganesque. Though he called for transforming America into a “kinder and gentler nation,” he adhered to Reagan’s supply-side economic dogma, which many liberals and others had denounced as an expression of a regressive, “trickle-down” practice that benefited only those at the top. “Read my lips: no new taxes,” he bellowed. Finally, to shore up his position with the religious right, he named as his running mate the undistinguished (at times buffoonish) Sen. Dan Quayle of Indiana, a darling of the evangelicals. Bush’s Democratic opponent was Gov. Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts, who won the nomination after Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware (caught up in a plagiarism scandal) and Sen. Gary Hart (caught up in an infidelity scandal) dropped out of the contest. Dukakis was a proud technocrat and a forerunner of the “New Democrats”—more centrist than their forebears—but was both uninspiring and still far too traditionally liberal to win in a center-right country in which the “L-word” had become a pejorative. Still, that was unclear at the time. On the heels of the Democratic National Convention, Dukakis held an unprecedented 17-point lead in some public opinion polls over Bush. Then the “gentleman” went on the attack. Bush held his nose and waded deep into the rancorous culture wars. Less than a decade earlier, Bush had held far more liberal views on abortion and the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (for women), but by the 1988 campaign he had jettisoned those liabilities and unapologetically flip-flopped on both issues. He hired some of the most ruthless campaign consultants available, notably Lee Atwater and Roger Ailes, the latter a future Fox News media mogul. Before the first debate with Dukakis, Ailes gave Bush some vicious advice. As governor, Dukakis had supported the repeal of state laws against sodomy and bestiality. Ailes whispered in Bush’s ear, “If you get in trouble out there, just call him an animal fucker.” After holding a focus group with swing voters in New Jersey, Atwater and company flooded the market with attack ads that implied Dukakis was somehow un-American. Americans were told that the governor had vetoed a law requiring teachers to lead their class in the Pledge of Allegiance (a genuine First Amendment issue); once called himself “a card-carrying member of the ACLU” (a free speech matter itself); opposed the death penalty (as had most 1960s-70s liberals and most voters in the Western world except Americans); and, finally, had overseen a program that gave a weekend furlough to a convict, Willie Horton, who failed to return and then raped and stabbed a Maryland woman. Atwater was, in his own words, determined to “strip the bark off the little bastard,” Dukakis. The Willie Horton scandal hurt Dukakis the most. The Bush campaign conveniently ignored the fact that many states had similar furlough laws, that Dukakis’ Republican predecessor had signed Massachusetts’ legislation into law, and that Reagan, when he was California governor in the 1960s, had overseen a similar program. This was a time for political war, not nuance. The most disturbing, controversial but effective TV ad run by Bush supporters lingered on a close-up photo of Horton, an intimidating-looking black man, in what was obviously a race-based message to voters. Bush was uncomfortable with the ad, though his more conservative, newly evangelical son, George W. Bush, thought it useful. And it was indeed effective in moving toward Atwater’s stated goal: “By the time we’re finished, they’re going to wonder whether Willie Horton is Dukakis’ running mate.” The final nail in the Democrat’s coffin came when he refused during a televised debate to support the death penalty even in a hypothetical case in which his own wife had been raped and murdered. It was an admirable stand, one that was ideologically defensible, but his intellectual courage won Dukakis few votes. The opinion polls rapidly shifted, and in the end Bush won with a slim 53 percent of the popular vote but a commanding 426-111 in the Electoral College. Still, Americans were disgusted and uninspired with both candidates. A paltry 50.1 percent of eligible voters turned out, the lowest participation rate since 1924. In other words, just over 25 percent of Americans actively supported the new president. Lower turnout, of course, then as now, favored the Republicans, especially with particularly low participation by the poor and minorities—traditionally liberal voters in a country that despite the “Reagan Revolution” still counted more registered Democrats than Republicans. When Bush entered the presidency in January 1989, he hardly had massive public backing. Qualified, Confident and (Sometimes) Competent: Bush and the World Ronald Reagan had shocked the nation, and the world, with his stunning turnaround on Cold War policy in regard to the Soviets. He proved his conservative detractors wrong: Premier Mikhail Gorbachev was a solid, actually monumental, partner. To his credit, Bush would mainly continue the Reagan relationship with Gorbachev and work to bring the Cold War to a bloodless and (hopefully) permanent end. From the unexpected fall of the Berlin Wall to the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Eastern Europe and, finally, to the eventual disintegration of the Soviet Union and resultant independence of the various Soviet republics, Bush proceeded with caution, competence and restraint. The result was more nuclear limitation treaties and a relatively peaceable end to a half-century standoff, surely the world’s most persistent of the 20th century. Bush even convinced Gorbachev to stand aside and allow Germany not only to reunite but join NATO! The catch was, as Bush was obliged to prudently promise, the U.S. agreed not to trample on the Soviet Union’s grave or expand the inherently anti-Russian NATO alliance any further. His successors would blatantly break that gentlemen’s agreement and extended NATO membership right up to the borders of Russia, including into the former Soviet Baltic republics. This would prove decisive in the later hardening of tensions between the West and a circumscribed Russian Federation. The result was a veritable Cold War 2.0. In Central America, Bush was far less responsible. Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega—an alleged CIA asset—had proved a useful partner so long as left-leaning movements held or contested power in nearby Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador. By Bush’s term, however, the socialist Sandinistas of Nicaragua fell from power and suddenly Noriega became a liability. His drug trafficking—which had previously been overlooked even amid the crack cocaine epidemic in the United States—and the killing of a few American troops by Noriega’s security forces gave Bush the “justification” necessary to invade the tiny country. It unfolded like old-school imperialism. Tens of thousands of U.S. paratroopers dropped on the narrow isthmus in the largest American combat action since Vietnam. Noriega was captured and his diminutive military quickly beaten, at the cost of some two dozen American lives. It was an utterly unnecessary, if popular, “patriotic display” for the U.S., a display that killed hundreds of Panamanian civilians. In the most serious international challenge that Bush weathered, on Aug. 2, 1990, Saddam Hussein’s formidable Iraqi army invaded and quickly conquered its tiny (but oil-rich) neighbor, Kuwait. This proved awkward for Uncle Sam. Perhaps half the world’s oil flowed through the Persian Gulf, mainly from Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Iraq’s threat to bordering Saudi Arabia was thus taken seriously. Bush seemed keen on military intervention from the start, but there were problems. Saddam was fresh off an eight-year aggressive war with Iran during which the U.S. had supported him and even provided him vital satellite-based intelligence. Furthermore, just days before the invasion, the U.S. ambassador to Iraq—in an epic gaffe—told the Iraqis that the U.S. “had no opinion on Arab disputes such as your border disagreement with Kuwait,” a comment seen by the Iraqis as a U.S. declaration that it would ignore an invasion of the neighboring country. It’s understandable, then, why Saddam was soon surprised by the forcefulness of the American and international response. Without a declaration of war, Bush quickly dispatched 100,000 troops to protect Saudi Arabia. This would soon alienate Islamist veterans of the 1979-89 war with the Soviets in Afghanistan—including Osama bin Laden—who offered to defend Saudi Arabia against the Iraqis and thus prevent an apostate occupation by Westerners of Islam’s two holiest sites. Those chickens soon came home to roost for Washington. It seems that Bush had decided on war from the first, but he waited until after the November 1990 midterm elections before seeking U.N. and U.S. Senate approval for military action. He didn’t have to do as much, based on earlier (troubling) precedent, but he chose to. The U.N. quickly passed the resolution, and Bush then sent his effective secretary of state, James Baker, on the road to form a representative international coalition. He did so in dramatic, and impressive, fashion—even signing on key Arab states such as Syria, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, and thereby lending local (Muslim) legitimacy to American military action. It was all over in six weeks. One can plausibly argue that Bush could have dislodged Saddam through means other than outright invasion and, had he done so, saved tens of thousands of Iraqi lives. In the minds of most, his prolonged “turkey shoot” air bombardment of fleeing Iraqi troops on the “highway of death” was excessive. U.S. casualties were remarkably light, with 148 deaths. Iraqi fatalities, by some estimates, would reach up to 35,000 soldiers and 3,000 civilians, levels seen as disturbing by much of the world. Bush was soon horrified by images of the massacres and called an end to the war after just 100 hours. While some burgeoning hawks, especially neoconservatives, thought the U.S. should seize Baghdad and overthrow Saddam, Bush prudently limited American objectives to the expulsion of the Iraqi army from Kuwait. At that point, even Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney supported Bush’s restraint, though the future vice president would later enthusiastically repudiate this early opinion. The Bush decision, in hindsight, undoubtedly represented the prudent course, as invading and then occupying sovereign nations historically has proved messy, lengthy and bloody. Nonetheless, after the U.S. military commander, Norman Schwarzkopf, hastily (and unilaterally) agreed to armistice terms that allowed Saddam to keep his helicopters in the air, Bush’s position deteriorated publicly when those crafts killed thousands of restive Iraqi Shiites and Kurds (groups long repressed by Saddam’s Sunni-dominated regime). Many on the American political right, including Bush’s son, the future president, soon came to believe that the senior Bush should have “finished the job” and driven to Baghdad. This lingering feeling and brutal sanctions that would result in some 500,000 Iraqi children’s deaths would prove to be the crucial, tragic outgrowths of an otherwise “neat” victory in the Persian Gulf. Reagan’s Third Term?: The Last Gasp of Republican Centrism Frustrated liberals at the time joked that Bush’s administration was little more than “Reagan’s third term,” more of the same and an extension of increasingly right-wing policies. In a sense it was. Bush initially doubled down on “Reaganomics,” and he too appointed a highly controversial and conservative Supreme Court justice and expressed scant concern for minorities’ civil rights (they weren’t part of his electoral base, after all). On the other hand, Bush often proved more practical and less enthusiastic about Reagan’s “voodoo economics.” Furthermore, on the environment and a few other issues, Bush was far more liberal or centrist than either his old boss or (certainly) the party faithful. This, and his willingness to practically shift course on supply-side dogma, earned him the permanent animus of many far-right, and increasingly powerful, conservatives. It may have cost him the next election. Bush’s postwar popularity, as is often the case, quickly diminished. A serious recession in 1990-91 was persistent and raised unemployment to 7.9 percent by June 1992, the highest rate in a decade. Large companies, such as AT&T and General Motors, fired tens if not hundreds of thousands. Many companies moved their manufacturing overseas into lower-cost, non-unionized areas, and it seemed that the Japanese were buying up more and more American businesses. Former Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Paul Tsongas even joked that the “Cold War is over, and Japan won.” Of course, the recession wasn’t solely Bush’s fault; rather, it was the expected (by many economists) fallout from Reagan’s high-deficit, low-tax, high-military-spending proclivities. Huge parts of the U.S. population—especially urban blacks and rural whites—lived in desperate poverty, and overall income inequality had exploded. In a genuine attempt to stem the recession, Bush forever angered—betrayed, said some of his erstwhile supporters—his conservative base, both in the populace at large and on Capitol Hill. He increased domestic spending in a (decidedly liberal) Keynesian stimulus package; authorized a taxpayer bailout of the crumbing savings and loan industry (another Reagan-era scandal); and finally, unforgivably to the political right, backed out of his campaign pledge of “no new taxes,” raising rates in order to lower deficits and slow the ballooning national debt. During “Reagan’s three terms,” after all, the federal debt had jumped to 50 percent of the gross domestic product from 32 percent. Bush’s moves may have been practical, perhaps even an absolute necessity, but they unleashed a congressional Republican rebellion. Some decided, then and there, not to back him in the 1992 election. House Minority Whip (and future Speaker) Newt Gingrich, by then a force on the Hill, walked out of a White House meeting with bipartisan legislative leaders just before Bush was to announce a plan designed to avoid an income tax increase. Bush later chastised Gingrich, complaining, “You’re killing us, you’re just killing us.” On environmental issues, Bush had some success and, like President Richard Nixon, proved willing to cross the aisle when he deemed a bill important enough. He would claim, accurately, that environment issues should “know no ideology, no political boundaries. It’s not a liberal or conservative thing we’re talking about.” (History has shown that much of Congress would not agree with that sentiment.) Bush’s support of the cap-and-trade compromise on greenhouse gas emissions (whereby companies had limits on output of such emissions but could trade excesses among themselves) turned out to be highly successful. This key element of what became the 1990 Clean Air Act lowered “acid rain” emissions by some 3 million tons in its first year. It was a rare, genuine, bipartisan accomplishment—though, predictably, it alienated dedicated deregulators in the Reagan coalition. If Bush showed only minimal interest in African-American or other race-based civil rights, he did secure the passage of the landmark Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), undoubtedly the most significant civil rights legislation since the late 1960s, which guaranteed various federal protections for over 43 million Americans. President Bush surely considered his appointment of Clarence Thomas, a conservative black judge, to replace the esteemed (first) black justice, the liberal Thurgood Marshall, as a civil rights achievement. This was debatable. In the aggregate, Thomas moved the court further rightward and, paradoxically, was a long-stated opponent of most federal civil rights legislation. Additionally, the then 43-year-old Thomas had limited judicial experience, having served just over a year on the D.C. circuit appeals court. His one major qualification, it seemed, was being both an African-American—nominated for a seat vacated by a black judge—and a rare black conservative. He was extremely right-wing, in fact. As Reagan’s head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), he had ironically opposed affirmative action and other civil rights programs. Then, one day before the Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation vote, a leaked FBI interview with law professor and reluctant whistleblower Anita Hill, a 35-year-old black former employee of Thomas at the EEOC, hit the media. She listed a litany of examples of Thomas’ longstanding sexual harassment of her during her tenure at the commission. The judiciary committee chairman, Sen. Joe Biden, already knew about the charges but had chosen to move forward anyway—at least until the FBI report went public. Biden reluctantly called Hill to testify. Thomas was furious and called the hearings and allegations a “high-tech lynching for uppity blacks,” suddenly and ironically bringing race into the picture despite his longstanding opposition to racial protections. Hill was treated horribly by a room full of male, mostly white and middle-aged or elderly senators. Her character was immediately impugned by Republican lobbyists and judiciary committee members themselves. The hearings quickly shifted to a focus on her character, rather than her accusations against Thomas. In the end, even Biden let Hill down. He once asked Thomas whether the judge thought Hill had made the whole thing up, and then decided not to extend the hearings and seek testimony from other women who also allegedly suffered sexual harassment at the hands of Thomas. It was not the prominent senator’s—and future vice president’s—finest moment. In the end, the Senate confirmed Thomas by a highly partisan vote of 52-48, the narrowest margin in the history of Supreme Court nominations. The next year, Los Angeles exploded in a fit of racial angst and violence. The immediate impetus was the shocking acquittal of four city police officers who had been caught on tape brutally beating a prostrate black suspect with their nightsticks. Relations between the mostly white police force and black Angelenos had long been strained. At the height of Reagan-era prosperity, 20 percent of residents of South-Central Los Angeles, then predominately black, remained unemployed. Rather than persistently address poverty, the Los Angeles mayor ordered Police Chief Daryl Gates to cut “criminality” to improve the city’s image during the 1984 Olympics. Thousands were arrested, mostly for nonviolent offenses, during indiscriminate police sweeps. More severe was Gates’ ongoing Operation Hammer, a response to the spreading crack epidemic of the late 1980s. The stated purpose of Hammer was to “make life miserable” for gang members, but the ultimate outcome was unending police raids that resulted in 20,000 arrests in the second half of the decade. The civil violence that sprang up after the acquittal of the four policemen abated only with the arrival of the California National Guard and U.S. Marines. The riots left 51 (mostly blacks) killed, thousands more injured and $700 million in property damage. More persistent, and influential, was the significant loss of trust in the police by urban blacks, and a chasm, nationwide, between blacks and whites in how they viewed the riots. Bush may have appointed a black Supreme Court justice, but clearly grievous problems from America’s “original sin” of racial caste and inequality had not disappeared. Liberalism Betrayed: Bush, Clinton and the Election of 1992 Single-term presidents are more uncommon than it may seem. In the 20th century, only William H. Taft, Herbert Hoover, Gerald Ford (who served only part of one term), Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush failed to be re-elected. In the immediate aftermath of the Persian Gulf War, in the spring of 1991, Bush’s approval rating was through the roof and he looked unbeatable. Just a year later, with the economy lingering in what was really a Reagan-induced recession, and Bush’s own base frustrated with his tax hike and overall centrism, the president’s public approval ratings hit a pathetic 35 percent. The incumbent faced a rare and serious challenge from the right wing of his own party, with Reagan communications director and culture warrior Patrick Buchanan unsuccessfully facing off against the president. Even after its candidate lost, the Buchanan wing of the party never fully embraced Bush in the 1992 contest. And, in a speech nominally endorsing Bush at the Republican National Convention, Buchanan threw gasoline on the fire of cultural conflict. Sounding very different from the establishment president, Buchanan declared war on liberals and Democrats, even implying that they weren’t “real” Americans. “My friends,” he said, “this election is about more than who gets what. It is about who we are. … There is a religious war going on in our country. It is a cultural war … critical to the kind of nation we will one day be. …” Though Bill Clinton, Bush’s opponent in the general election, was a neoliberal “New Democrat,” far more conservative than almost all the Democratic liberals of the past, Buchanan portrayed him and his wife, Hillary, as radical, godless leftists. He told an impassioned convention audience, “The agenda that Clinton & Clinton would impose on America—abortion on demand … homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat units … is not the kind of change America needs.” Piling on, Republican National Committee Chairman Richard N. Bond gave a TV interview in which he claimed of the Democrats, “These other people are not the real America.” Despite these alarmist, exaggerated attacks from the right-wing base, Bill Clinton refused to play into his opponents’ hands. He would not make the same mistakes—those of honesty and principle—that Dukakis had made four years earlier. During the campaign, Gov. Clinton even made a show of flying back to Arkansas to oversee the execution of a man so mentally impaired that he asked prison guards to save the dessert from his last meal so he could eat it later. Clinton then permanently alienated civil rights icon Jesse Jackson when, appearing before the Rainbow Coalition, he chose to denounce a rapper named Sister Souljah who had emotionally asked in the wake of the Los Angeles riots, “If black people kill black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?” Clinton avoided the obvious nuance and hyperbole in the rapper’s remarks and chose—in what was forever dubbed his “Sister Souljah moment”—to use the occasion to distance himself from traditional liberals. Clinton was a natural politician, arguably one of the best in modern American history. He knew what won elections—“kitchen table” issues—and fiercely counterattacked on the economy. He portrayed the privileged Bush—juxtaposed with his own rise from poverty—as out of touch with the daily financial struggles of average Americans. Clinton, on the other hand, “felt their pain,” or so he claimed. The Democrat’s campaign was a slick public relations machine with laser focus. In the campaign’s “war room,” a sign on the wall read, “IT’S THE ECONOMY, STUPID.” It was, indeed. Clinton would ride to victory on this economic wave, aided, significantly, by the surprisingly potent self-financed third-party campaign of billionaire Ross Perot. Perot hammered Bush about the rising deficits and national debt and virulently opposed the president’s proposed North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which, ironically, Clinton would later support; Perot thereby stole deficit-hawk Republican votes from Bush, allowing Clinton, the Democrat, to (oddly) run as a beacon of fiscal conservatism. The president was cooked. Clinton took 43 percent of the popular vote, to Bush’s 38 percent, with Clinton aided further by the 19 percent who fled into Perot’s arms. Clinton had no mandate, and he knew it. His 43 percent portion of the popular vote was the lowest received by a winning presidential candidate since Woodrow Wilson. His election was not a triumph of liberalism, but a slick piece of political work almost wholly disjointed from any meaningful ideology. So who exactly were the Clintons? Well, Hillary Clinton—a lawyer and activist—was a favorite target for conservative attack dogs. According to Buchanan, she was a “radical feminist.” She was hardly that. Hillary Rodham began her political life as a strident Republican. As a youth she canvassed for Richard Nixon over John Kennedy, then backed Barry Goldwater for president in 1964, considering herself a “Goldwater Girl.” At Wellesley College she even served as president of the Young Republicans. Eventually, however, her principled opposition to the Vietnam War and growing (yet quite moderate) feminism drove her to sign on with the Democrats. Indeed, Hillary Clinton would gradually shift rightward during her time as first lady, then as U.S. senator from New York and, finally, as a two-time presidential candidate. Yet all that lay in the future. Bill was a 46-year-old charmer who had risen to become a youthful, unlikely governor of Arkansas. He has been described as a “bridge between the Old Democrats and the New.” As a Southerner he could appeal to the party’s traditional base, but as a (once) progressive, well-educated professional, he could also connect with the identity politics of the new base. All the while, Clinton was, as the historian Jill Lepore astutely labeled him, “a rascal.” During the primaries he hung in reports of alleged infidelities and shady real estate transactions came to light. He never really admitted to much, circumventing questions and equivocating time and again. He managed to survive—he would ultimately prove to be the ultimate political survivor—and squeaked into the highest office in the land. In the process, he would become the undertaker for progressive hopes and dreams. Liberalism, as Americans had known it, was dead by 1992. If Reagan and Bush knocked it down, the “New Democrat,” Clinton, drove the fatal stake in its heart. This would become ever so apparent during his proceeding two terms. * * * George H.W. Bush, the 41st president, seems, in retrospect, a transitional figure wedged between the “Eisenhower Republicans” of old and the growing influence of neoconservatives and evangelicals who would come to dominate the party. Not that Bush was a martyr or an inclusive bipartisan leader; he was not. He appointed advisers more ruthless than he and ran rather dirty election campaigns. His administration was tarnished by a poor economy in recession, though it must be said this was more an outgrowth of Reagan (and initially Bush’s) dogmatic adherence to “trickle down” economics. Bush, though far less vicious than his Republican successors, was no benefactor of the liberal social welfare state, nor did he concentrate much on persistent issues of racial and economic inequality. Ultimately, his was merely a kinder, gentler—perhaps less doctrinaire—version of Reaganomics. On his watch, hardly anything substantive was done to slow soaring income inequity, as (had been the case since the early 1970s) the poor generally got poorer and the rich richer. Bush, like John Kennedy before him, had always preferred, and felt most comfortable in, foreign affairs. After all, much of his career had prepared and suited him for global policy. Even here, however, Bush’s term was a mixed bag. He waged “Grenada 2.0”—the ludicrously unnecessary invasion of Panama—and probably killed many more fleeing Iraqi troops than was necessary in the Persian Gulf War. Then again, he carefully, and deftly, worked with Russian Premier Gorbachev to finish the work he and Reagan had begun, ushering in an astonishing, bloodless end to the Cold War. That monumental and dangerous affair certainly could have gone another way. And, though his leadership during the Gulf War was uneven, he demonstrated presciently prudent restraint, limiting U.S. and coalition goals to the expulsion of the invading Iraqi army from Kuwait while eschewing a hasty march toward Baghdad and regime change. His son, George W. Bush, would prove far less judicious in 2003. On the surface, Bush and his opponent in 1992, Bill Clinton, seemed polar opposites. One was a war hero, the other evaded service in Vietnam. One was born into wealth, the other suffered poverty in tiny Hope, Ark. Bush was, at root, an establishment Yankee, Clinton Southern-born and -bred. Bush was reserved, awkwardly professional and at times stiff, Clinton was smooth, played the saxophone and had smoked marijuana (though he claimed never to have inhaled). Still, politically, Clinton was not totally unlike his predecessor. Neoliberalism, a cheap, facile imitation of conservatism, defined Clintonianism. The eight years that followed Clinton’s victory over Bush in 1992 proved—on a policy scorecard—hardly divergent from “Reagan’s three terms.” The old consensus forged by Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson was finished, defeated decisively in the many battles of the transitional 1980s. In the following decades, the culture wars divided Republicans and Democrats ever further apart, but on foreign and fiscal policy there proved to be barely any light between two increasing corporate parties beholden to Wall Street and the arms industry. The consequences, for Americans and the world, would prove tragic indeed. * * * To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

Source URL |