| Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”? Below is the thirty-third installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past. *****

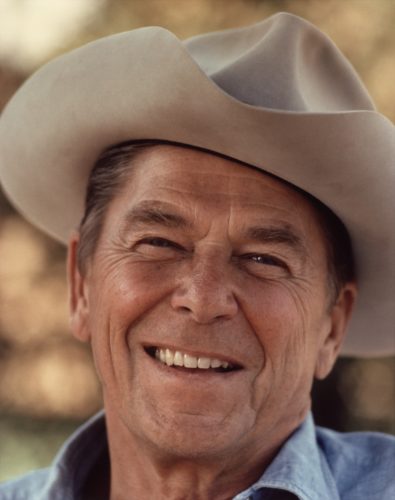

It was no accident. Indeed, candidate Ronald Reagan knew exactly what he was doing. It was August 1980, at the height of presidential election fever. Visiting Mississippi, once a symbol of the solid Democratic South, Reagan chose the Neshoba County Fair for a key campaign speech. To beat incumbent President Jimmy Carter, he would have to turn the Deep South Republican. The fair was in the same county as Philadelphia, Miss., and only seven miles from that town, forever associated with the murder of three civil rights activists (one black and two white) just 16 years earlier. It was a bold move by Reagan. Stepping up for the occasion, he railed about big government and thundered in ever-so-coded language, “I believe in states’ rights.” In a state that still proudly flew the Confederate Battle Flag, no doubt the mostly white crowd of some 15,000 knew, and loved, the racial undertones of such a statement. The states’ rights mantra had long amounted to little more than a justification of racism by another name. The only right many states tended to focus on was their right to suppress black voting and maintain the segregation of public life. Reagan’s performance at the fair was an insult to the memory of the once vibrant civil rights movement. And it was understood as such. The tactic worked. Reagan all but swept the South in the 1980 race, and the region has essentially remained Republican ever since. (Among Southern states, only West Virginia and Georgia went for the Georgian who occupied the Oval Office.) The Sunbelt, that vast southern expanse from Florida to California, would prove to be a stronghold of Republican loyalty for decades to come. Though President Richard Nixon inaugurated the Republicans’ “Southern Strategy,” it was Reagan who perfected it. The presidency of Reagan, like that of many of the chief executives of the United States, was complex. He was undoubtedly conservative and had run to the right of his primary opponents in 1980. Political ideology aside, he was an astute politician, willing to compromise and never so doctrinaire as liberals feared. On foreign policy he could shift from hawk to dove on a dime, exuding “toughness” but also, at times, demonstrating restraint. He cut taxes and some social programs but was smart enough not to dismantle the highly popular Social Security and Medicare programs, held dear by liberals before and afterward. Though far more ideological than Dwight Eisenhower and—even—Nixon, he was at root a pragmatist. For the left, he was ultimately something much scarier than those two earlier Republican presidents: a charming, effective and highly popular figure of the right. He bent with the prevailing winds and harnessed their energy in continuing the gradual rightward policy shift that had been occurring since the end of the presidency of Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson. By the time he left office in 1989, he had not quite transformed Washington, but he had nudged it farther to the right. The game had changed during his tenure, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s old liberal coalition was more fractured than ever. Democrats sensed trouble in Reagan’s peculiar popularity and would rarely run a zealously liberal presidential candidate over at least the next 30 years. After the tumult of the 1970s, white America had indeed grown more conservative, or at least more cynical. Faith in the transformative power of federal intervention was replaced by a sense that government was “the problem.” Sick of the identity politics and the countless causes of the late 1960s and early 1970s, many had grown nostalgic for traditional (read: conservative) values and gradually had turned more socially conservative. America hadn’t quite abandoned the Democrats, per se, but it greatly weakened their traditional political grip. Henceforth, increasingly more conservative candidates ran for local and national office on the GOP ticket. The Republican Party, quite certainly, was revolutionized by Reagan. Though he clearly was a conservative, Reagan is difficult to nail down. He slashed taxes and some social programs yet left others untouched and even raised taxes on one occasion. He was a remarried divorcé who voiced the values of the evangelical right. (His first marriage, a union of eight and a half years with actress Jane Wyman, had ended in 1949.) He benefited greatly from support of the right-wing Christian group Moral Majority but shied away from its demand that abortion be outlawed. He was a Cold Warrior who promised to bury détente but later negotiated substantial nuclear reductions and oversaw a thaw in the dangerous conflict with the Soviet Union. He was elected as a hawk’s hawk but rarely put American soldiers in harm’s way, instead using airpower and local proxies to kill hundreds of thousands. Indeed, decades later, President Barack Obama would adopt a formula of Reagan-like “restraint.” When it comes to Reagan, what he did is often less sweeping than what he allowed, and made possible eventually. He implemented a rightward sea change that would carry both parties in a more conservative direction, often with tragic results. One cannot understand America’s present without grappling with the realities of its Reaganite past. Reagan was never simple and rarely consistent but always confident. Throughout his two terms one can track the widening political gap between truth and fiction, the reality of limitations and the fantasy of the “more” culture. Reagan won two elections and control of his own legacy for one major reason: He told Americans what they wanted to hear, consequences be damned. A Republican Tide?: The Election of 1980 Reagan won the 1980 election by portraying Carter—who had already shifted rightward—of being weak on national security and hopelessly liberal in economics and on various cultural issues. He built a winning coalition that rivaled FDR’s liberal alliance. First came his hardcore base—white Southerners and an increasing vocal and powerful religious right. The organizing potential of evangelicals was impressive. In 1979-80 alone, the famous Baptist minister Jerry Falwell, a leader of the burgeoning movement, raised some $100 million for the causes of Moral Majority, which he and associates had founded. That alone was more money than the Democratic National Committee raised for the entire election of 1980. So it was that Reagan and other Republicans, who traditionally were unconcerned about abortion, learned to speak “pro-life” language (although they did not actually do much about the issue itself). The abortion debate also motivated Reagan’s advisers to put devout Catholics on his campaign team. Add to this two other key, longtime constituencies—corporate interests and national security hawks—and the Reagan coalition looked fearsome. But it was a new, different constituency—white, Northern, ethnic blue-collar workers sick of what they perceived as liberal excesses—that would remake the picture. With these voters on board, Reagan could hardly lose. Some of these supporters, voting Republican for the first time, came to be called “Reagan Democrats.” In addition to his political team-building, Reagan’s personality was a plus. He had been a famous movie actor and even at almost 70 years of age looked healthy and fit. Unsurprisingly, then, Reagan with his soothing baritone voice proved an effective communicator. He seemed everything President Carter was not. Most of all, Reagan exuded self-confidence and extraordinary optimism. His own daughter admitted that his boundless buoyancy and cheerfulness were “enough to drive you nuts.” But it was the struggling economy and Carter’s seeming inability to rejuvenate it—though this was often out of his control—that sank the incumbent president once and for all. Reagan campaigned against the government with a vigor rarely seen. “Government,” he would say, “is like baby, an alimentary canal with a big appetite at one end and no sense of responsibility at the other.” He promised deregulation and local control over social programs. He even vowed (though he didn’t ultimately do so) to dismantle the Department of Energy and the Department of Education. Reagan cloaked these harsh positions in restrained, populist soundbites. He would ask audiences during his campaign against Carter, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” and he fed Republican crowds a favorite line: “A recession is when your neighbor loses his job, and a depression is when you lose your job, and recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his.” Although Reagan defeated Carter by almost 10 percentage points in the popular vote and took a lopsided victory in the Electoral College, he hardly had the mandate he claimed. He gained only 50.7 percent of the popular vote in a three-way race (independent candidate John B. Anderson captured 6.6 percent), and only 52.8 percent of Americans of voting age cast ballots, the lowest such figure since 1948. Thus it was less than 27 percent of eligible voters who actually chose Reagan. Clearly a majority of Americans had not voiced support for the indelible transformation the candidate planned for the governmental system. A gender and racial gap was growing. Women were far less likely than men to support Reagan. Almost all minorities generally voted Democratic. The great fault lines of American political life were expanding and hardening. Republicans won control of the Senate in 1980, despite Democrats maintaining a majority in the House. Key Democratic liberals lost their congressional seats, including Sen. George McGovern, who had been the 1972 presidential candidate, and Sen. Frank Church, who had led hearings on excesses in the areas of national security and intelligence operations. Even if Reagan’s “revolution” wasn’t total, it was profound. Democratic Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, lamenting the damage done to his party, observed that a “great tidal wave hit us from the Pacific, the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Great Lakes.” If Reagan seemed unsophisticated on policy issues, it hardly mattered. As Bill Moyers, a former top aide to Lyndon Johnson, put it, “We didn’t elect this guy because he knows how many barrels of oil are in Alaska. We elected him because we want to feel good.” Critics, with some justification, saw Reagan as more show than substance. Nonetheless, they underestimated the extent of his political acumen. He ran on the mythology of America and on the nation’s limitless horizons. He urged Americans to “believe in ourselves and to believe in our capacity to perform great deeds, to believe … we can and will resolve the problems which now confront us.” “Why,” he asked, “shouldn’t we believe that? We’re Americans!” Patriotic pageantry was another Reagan tactic. Michael Deaver, a top Reagan aide, would later describe Reagan’s successful 1984 re-election campaign by saying “[w]e kept apple pie and the flag going the whole time,” and that could well be applied to Reagan’s entire tenure. Reagan would earn his legendary nickname of the Great Communicator by seamlessly explaining complex issues in simple, plain language. Speaker O’Neill praised the former actor’s skills in politics, saying that Reagan “might not be much of a debater, but with a prepared text he’s the best public speaker I’ve ever seen.” Reagan’s communications team was a smooth-running machine. Top aides would start each morning with the “line of the day,” a single theme that would infuse all presidential business and public relations for the coming hours. “We had to think like a television producer,” White House spokesman Larry Speakes explained, because favorable public exposure for the president on TV would consist of only “a minute and thirty seconds of pictures to tell the story, a good solid sound bite.” With a Hollywood star in the Oval Office it seemed an unbeatable communications strategy. In the aftermath of Reagan’s 1980 victory, The Washington Post’s Haynes Johnson declared “it was clear to all the wise men in Washington what historic shift had occurred. A Reagan Revolution … had altered the American political landscape with profound implications for the nation and the world.” That remained to be seen. Reaganomics: How to Craft an Oligarchy The newly inaugurated president, who in large part had won the election by berating Jimmy Carter about the nation’s financial woes, knew he would live or die on the state of the economy. It received immediate attention as Reagan set out, it seemed, to restructure the whole system. He focused on three main areas: increased military spending, lower income taxes, and deregulation of the financial system and other facets of the vast federal bureaucracy. All of this was grounded in Reagan’s interpretation of newly popular “supply-side economics.” Theoretically, so went the thinking, lower taxes would stimulate economic growth once individuals and corporations had more cash in hand. Thus, federal tax revenue would not fall and might actually rise because of increased incomes stemming from greater entrepreneurial spirit. The problem turned out to be that the theory didn’t work as advertised. Probably a majority of economists were skeptical of supply-side theory—which came to be known as “Reaganomics”—and many claimed Reagan’s ideas were unrealistic, a “have your cake and eat it too” delusion. Could Americans be made to believe that lower taxes and simultaneous raises in military spending would have no negative consequences? When he was competing for the Republican presidential nomination, George H.W. Bush, now the vice president, had complained about Reagan’s “voodoo economics.” With Reagan in office and trying to implement his economic plan, many Americans were on the fence regarding the supply-side notion. In addition, the Democrats still held the House. By March 1981, it was unclear whether Reagan had the votes to push through his tax-cut bill. Then, on March 30, a deranged young man nearly killed the president when he fired six shots at him. A ricocheted bullet lodged in Reagan’s left lung. Through it all, the president seemed to handle his fate with grace, courage and humor. Just before surgeons began to operate, Reagan quipped to them, “Please tell me you’re all Republicans.” His popularity soared in the aftermath of the assassination attempt. Thus the passage of Reagan’s ambitious tax bill was virtually assured. House Speaker O’Neill would admit as much, declaring, “Because of the attempted assassination the president has become a hero. We can’t argue with a man as popular as he is.” There was more to it than sympathy votes for a wounded president. Reagan knew how to work the Congress, and work it he did. During the first hundred days (some of which he spent in recovery) Reagan met with 467 members of Congress, and, though he rejected large changes to his tax bill, he proved amenable to compromise. O’Neill admitted he had underestimated the man and complained of “getting the shit whaled out of me!” Reagan promised to cut income taxes 30 percent over three years and eventually managed to lower the top income tax bracket from 70 percent to 28 percent (though he would marginally raise tax rates before then). The comprehensive budget bill also cut social spending—in food stamps and public assistance—and canceled a Carter-era jobs program that had provided work for 300,000 people. This particularly irked some liberals, especially when such frugality was juxtaposed with the expensive clothing that Nancy Reagan wore to public functions. The first lady attended the 1981 inaugural balls in an ensemble that reportedly cost $25,000. For the 1985 galas, the cost of her outfit was said to have almost doubled, to $46,000. After President Reagan cut some 350,000 Americans from the rolls of Social Security disability payments, a wounded Vietnam veteran and Medal of Honor recipient, Sgt. Roy Benavidez, testified before Congress in June 1983 that the “administration that put this medal around my neck is curtailing my benefits.” All told, Reagan ushered in $140 billion in social spending cuts in his first three years alone. New restrictions reduced the number of children eligible for subsidized school lunches by half a million. And, by lowering the highest federal tax bracket to 28 percent, Reagan had created an economy in which, according to reporter and author Donald L. Bartlett, “In 1988, a school teacher, factory worker, and billionaire can all pay 28% [in taxes].” Reaganomics seemed to affect the “two Americas” very differently, and its excesses could appear quite coarse. For example, in 1981 Reagan’s Agriculture Department changed regulations to classify condiments such as relish and ketchup as vegetables in free school lunches, thus saving money on fresh produce. That same week the White House ordered $209,508 worth of china with the presidential seal embossed in gold. Regressive taxation and inequality seemed triumphant. That was the point, according to Reagan administration Budget Director David Stockman. Unlike the cozy rhetoric employed by other supply-siders, Stockman’s assessment was harsh and clear. He knew that tax cuts would never sufficiently increase productivity and thus government revenue. He knew there would be deficits, and he welcomed them, knowing that legislators would then come under pressure to cut domestic spending rather than take the politically unpopular step of raising taxes. Stockman called it the “starve the beast” strategy. He explained that the beast is big government and it should be starved by cutting taxes and reducing revenues so programs have to be cut back. (Years later, Stockman would disown Reaganomics.) Reagan tended to soften Stockman’s tone in his own public pronouncements, but even the president could seem heartless, as in a television interview where he claimed that the “homeless … are homeless, you might say, by choice.” Many working and middle-class Americans went along with the deep cuts to poverty reduction programs. They had been hammered time and again by conservatives with the message that welfare was bankrupting the nation and most of its recipients were unworthy. This was simply false. Welfare, such as it was, accounted for only 8 percent of government outlays in 1986, compared with 32 percent for defense. In addition to cutting taxes and slashing certain aspects of the social safety net, Reagan also deregulated various industries and federal agencies. “Government,” after all, as he repeatedly said, is “not the solution, it’s the problem.” The consequences of Reagan’s deregulation bonanza was severe at times. The lack of oversight encouraged risky behavior on Wall Street and ushered in a savings and loan crisis. The federal government had to bail out key financial institutions in what became the costliest financial scandal up to that point in U.S. history. In addition to the financial sector, Reagan also deregulated environmental restrictions. He personally believed the environment was not in serious danger and ignored scientific evidence of global warming, setting a precedent for Republican orthodoxy for decades to come. Indeed, his administration cut research funding for renewable energies by some 90 percent. And why not? Just after he took office, 23 oil industry executives contributed $270,000 to redecorate the White House. As Jack Hodges, the Oklahoma City-based owner of Core Oil and Gas, bluntly put it, “The top man of this country ought to live in one of the top places. Mr. Reagan has helped the energy business.” Reagan had a particularly nasty habit of appointing officials who were hostile to the very government agencies they led. His secretary of the interior, James Watt, believed that protecting the environment was far less important than Christ’s imminent return, divided people into two categories—liberals and “Americans”—and vowed to “mine more, drill more, cut more timber.” To lead the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Reagan chose a Florida businessman, Thorne Auchter, whose construction company had regularly been fined by OSHA. Auchter proceeded to cut OSHA inspections by more than 20 percent. A Reagan appointee who was the first ever female head of the Environmental Protection Agency believed that the EPA regulated businesses too aggressively. With such appointees atop these agencies, Reagan created a self-fulfilling prophecy in which government did appear broken and inherently problematic. Reagan, though once the president of a labor union, the Screen Actors Guild, was a veritable union buster. When tens of thousands of air traffic controllers threatened to strike for better pay and benefits, Reagan gave them a 48-hour ultimatum to return to work. Only 38 percent returned to the job, and the president followed through, fired 11,000 others and sent military controllers to fill the gap. Reagan single-handedly destroyed the controllers union and sent an unmistakable message to many others. Greatly demoralized, organized labor was on the retreat during the 1980s as membership rates and the number of annual strikes plummeted to record lows. Reaganomics’ consequences were mixed but mainly negative. After an initial recession and increasing unemployment in 1981-82, the economy would essentially right itself and growth would return. Inflation did stabilize, largely thanks to the tight-money schemes of the Carter-appointed head of the Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker, whose harsh austerity measures may have caused a recession but did level out inflation over time. Unemployment averaged 9.7 percent during what Democrats labeled the “Reagan recession,” the highest rate since the Great Depression. In the long run, however, the painful Volcker medicine cured runaway inflation. Nevertheless, when Reagan left office in 1989 he left the new president, his former vice president, with an economy in which one-quarter of children still lived in poverty. After all, a growing economy is not necessarily a healthy economy, and Reaganomics no doubt did some structural damage. Lower taxes and greater military spending turned out just as one might suspect. During Reagan’s two terms the national debt tripled. His administration never balanced a budget in eight years. Federal debt as a percentage of GDP jumped from 33 percent in 1981 to 53 percent in 1989. Reagan adviser David Stockman admitted in late 1981 that “[n]one of us really understands what’s going on with all these numbers.” Even more concerning was that income inequality—the gap between the rich and the poor—was on the rise during the Reagan years. House Speaker O’Neill saw the problem and fired a salvo of dissent. “When it comes to giving tax breaks to the wealthy in this country,” he said, “the president has a heart of gold.” During Reagan’s tenure, the income of the top 20 percent of families rose by an average of $10,000 per year, whereas for the bottom 20 percent wages slowly declined. In 1980, CEOs earned an average salary 40 times higher than a factory worker’s. By 1989, they were making 93 times as much. Such excesses bordered on the absurd. The Reagan tax cuts only aggravated the inequity. The taxes that stayed put, like the Social Security payroll tax, were often highly regressive, with most of the weight falling on low-income people. This only contributed to rising economic inequality. CEOs of major corporations saw their average salaries quadruple between 1980 and 1988, from $3 million to $12 million annually. The “Forbes 400” list saw tripling of the net worth of the richest Americans. Corporate leaders would pay Reagan back in spades. During the 1984 election campaign, political action committees (PACs) favoring the GOP raised $7.2 million, compared with other PACs raising just $650,000 for the Democrat presidential candidate, former Vice President Walter Mondale. Reagan won in a near-record landslide. Shaken by this defeat, the Democratic Party began a rightward shift of its own, with “New Democrats”—such as Southern governor Bill Clinton and Missouri’s U.S. Rep. Richard Gephardt—in the vanguard. Democrats, the insurgents realized, would need to start sounding like Republicans if they hoped to ever win again. For the Democratic Party this began the long streak of neoliberalism that remained dominant for decades to come. It mattered little that Mondale was correct in many of his assessments and predictions. The former vice president accurately noted that Reaganomics, if continued, would hollow out the middle class, making the rich richer and the poor poorer. Indeed, in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, Mondale clamored, “Four years ago, many of you voted for Mr. Reagan because he promised you’d be better off. And today the rich are better off. But working Americans are worse off, and the middle class is standing on a trap door.” While it wasn’t true that all working Americans were worse off in the increasingly prosperous ’80s, Mondale’s warning was a prescient harbinger. Nevertheless, most Americans were attracted to Reagan’s “Make American Great Again” rhetoric and the ubiquitous, soothing 1984 Reagan TV advertisement popularly known as “Morning in America.” The ad, carefully produced by experts in Radio City Music Hall, featured Norman Rockwell-like, suburban nostalgia and patriotic pageantry. The ad’s effectiveness demonstrated that most Americans were captivated by Reagan’s unflinching positivity. During his re-election campaign, Reagan even co-opted the decidedly antiwar anthem “Born in the USA,” by Bruce Springsteen, and played it at rallies for audiences who clearly knew only the chorus and not the verse lyrics. Springsteen reacted angrily to the misappropriation of his song, saying, “You see in the Reagan election ads on TV, you know, ‘It’s morning in America,’ and you say, well, it’s not morning in Pittsburgh. Its not morning above 125th Street in New York [Harlem]. It’s midnight and there’s, like, a bad moon rising.” Decades later, the musician deftly summarized what had occurred: “This [when Reagan used the song and even directly praised its ‘message of hope’] was when the Republicans first mastered the art of co-opting anything and everything that seemed fundamentally American, and if you’re on the other side, you were somehow unpatriotic.” Through it all, though, the outcome in 1984 seemed a fait accompli. Reaganomics may have eventually killed the inflation monster, but it didn’t seriously reduce poverty. In 1989, 31.5 million Americans lived below the poverty line. Also, the number of homeless Americans doubled in the Reagan years, from 200,000 to 400,000. What’s more, despite the supposedly miraculous Reagan-induced economic turnaround, overall increases in real per capita income averaged only 2 percent per year, much more modest than during the immediate postwar Good Old Days, and not much greater than growth had been in the late 1970s. The highest increases, of course, were among the wealthiest economic quintiles. Even the federal minimum wage remained stagnant, at $3.15 per hour, throughout Reagan’s tenure. By the late 1980s, some 14 percent of Americans lacked health insurance and the corporate interests backing Reagan would hardly countenance any legislative action to improve these rates. When he left office, the U.S. was the only developed nation in the West without universal health coverage. The real wages of working people, meanwhile, were stalled, and the fastest-growing occupations tended to be low paying and in the service sector. Farm foreclosures rose. Furthermore, due in part to foreign competition, the United States shifted from being one of the world’s largest creditors to the world’s largest debtor. All this contributed to the growth of a consumerist culture in the 1980s. The president encouraged such behavior, stating in 1983, “What I want to see above all is that this remains a country where someone can always get rich.” It seemed that young, upwardly mobile professionals, “yuppies,” had become the role models of the Reagan era. A best-selling memoir/business-advice book was published under the name of a young real estate magnate, Donald Trump, and it became a symbol of the yuppie culture. The consumerist values manifested even in popular films, such as Oliver Stone’s 1987 “Wall Street,” in which a rather Trump-like character famously declares “Greed is good.” It seemed that onetime socially conscious and liberal baby boomers had become increasing conservative and obsessed with the accumulation of wealth. According to one report, a third of all Yale seniors graduating in 1985 applied for jobs at First Boston Corp., a leading Wall Street investment house. These developments represented a dramatic change from the progressive activism of the 1960s-70s. Race was a factor in economic inequality. References to cutting the social welfare assistance of black Americans were generally coded in the Reagan years as cuts in “unearned” benefits. Reagan regularly denounced “welfare queens”—meaning inner-city unwed black mothers—and exaggerated the magnitude of welfare fraud. It should be noted that the New Deal and Great Society programs—such as Social Security and Medicare—that he left undamaged are broadly associated with huge (read: mostly white) segments of the population. African-Americans resented Reagan’s relative disinterest in the urban issues of crime, poverty and unemployment. The spreading crack cocaine epidemic gave greater urgency to black pleas for attention. It seemed Northern urban blacks faced a perfect storm of declining manufacturing jobs, de facto segregation, failing schools and rising street crime. In 1985, a series in the Chicago Tribune described the situation: The existence of an underclass is not new. … What appears to be different … is the permanent entrapment of significant numbers of Americans, especially urban blacks, in a world apart at the bottom of society. And for the first time, much of the rest of America seems to be accepting a permanent underclass as a sad, if frightening, fact of life.Reagan also took no serious action to support school integration, and resources for inner-city schools remained inadequate. African-Americans were particularly hard hit during the 1981-82 recession, with unemployment reaching 19 percent in their community. Even as the economy stabilized, black unemployment seemed fixed at twice the rate of whites. Furthermore, while a 1983 poll demonstrated that 46 percent of whites believed the economy was improving, only 17 percent of blacks agreed. There was a distinct sense in the black community that Reaganomics didn’t serve African-Americans. Reagan’s was not a diverse administration. He had topped Carter by substantial margins in capturing the vote of whites and the vote of men in 1980, and the president would serve and appoint white men to a considerable degree. It was in the courts that Reagan built a lasting conservative legacy. In eight years, he appointed 368 district and appeals court judges (nearly half the national total on the bench), the vast majority of them conservative white males. Just seven were black, and 15 were Hispanic, a combined 6 percent of the total of appointees. Reagan also placed three Supreme Court justices during his tenure, including the reactionary Antonin Scalia, an “originalist” who believed the Constitution must be taken literally in its 18th-century context. With these high court and district court appointments, Reagan launched a long-lasting change in the judiciary. He ensured there would be little or no federal action to support proactive school integration, affirmative action or other racially tinged causes. Instead, Reagan’s approach was punitive and based on “law and order.” According to Reagan and most of his judicial appointees, crime, not underlying poverty and segregation, was the problem. It was thus unsurprising that the number of incarcerated Americans doubled to nearly 1 million during the Reagan era. And there were other complaints about Reagan. He wasn’t a particularly hard worker, it seemed. He refused to hold early staff meetings, needed naps and called it quits by 5 p.m. There were even rumors that he would doze off in Cabinet meetings. He once even failed to recognize his own secretary of housing and urban development at a public function, despite the man being the only black Cabinet officer. Few in the public knew of these shortcomings, and it is doubtful that most Americans would have cared had they known: Reagan’s popularity remained high. O’Neill characterized the president as “most of the time an actor reading lines who didn’t understand his own programs,” someone who “would have made a hell of a king.” Sometimes it even seemed that Reagan could hardly separate fact from fiction. He repeatedly told a patriotic yarn in public speeches about a World War II bomber pilot who decided to stay with a trapped crew member rather than eject from the burning plane. “Never mind, son, we’ll ride it down together,” Reagan recounted the pilot telling the injured man. The problem is this event never happened, except (fittingly) in a World War II film, “A Wing and a Prayer,” starring Don Ameche and Dana Andrews. The president—whose own military service was stateside churning out training and propaganda films mainly in Culver City near his California home—on occasion falsely claimed he had helped film the liberation of Nazi death camps in Europe. Reagan seemed to lack any self-awareness or contrition concerning his falsehoods; he kept repeating them. President Reagan also demonstrated a lack of leadership and empathy during the growing AIDS epidemic. By the mid-1980s, he had actually cut AIDS funding and had publicly mentioned the disease only once. Indeed, it wasn’t until a friend of his, the actor Rock Hudson, died of AIDS in October 1985 that Reagan showed any real interest in, or curiosity about, this then-fatal disease. Though he appointed a government investigator on the issue, Reagan was loath to take that expert’s recommendation to support broader sex education in schools or encourage the use of condoms. It’s easy to see why. Reagan’s evangelical base saw AIDS as a “gay plague” because a significant portion of its victims were homosexual. Such sentiments were on display even in Reagan’s inner circle. His director of communications, Pat Buchanan, insensitively wrote in 1983: “The poor homosexuals; they have declared war on nature and now nature is exacting an awful retribution.” In the end, Reagan’s sluggish response to AIDS ensured that on this issue, too, the U.S. would fall behind the nations of Western Europe, where sex education and birth control were readily available and AIDS infection rates far lower. On public policy in general, Reagan was no wonk and was hardly the ideologue that liberals had seen in their nightmares. However, his willingness to compromise, negotiate and reach across the aisle made him effective and thus, in a sense, a greater danger to liberalism. As early as 1980, an analysis in The Washington Post admitted that “[Reagan] is not one to let principles over-ride flexibility, and everyone who knows him concluded that he’s a nice guy, a happy secure person who likes himself and other people. …” As mentioned earlier, Reagan was smart enough not to harm the sacred cows of Social Security and Medicare. He even inched leftward on immigration, passing a reform act that gave “amnesty”—a temporary path to citizenship—to millions of undocumented workers. Such flexibility on immigration would become anathema to future rightward-leaning Republicans. In the near future, Republicans would move right, and Democrats left, on immigration and a number of other issues. Reagan’s domestic legacy, then, proved to be his ability to achieve conservative goals while maintaining broad public support and the veneer of civility. His GOP successors proved far less amenable to compromise, and it was Reagan who made possible the rigid sorts of later years. All told, Reaganomics and Reagan’s domestic program as a whole were probably more popular than they should have been. Inflation did level off and persistent unemployment finally fell, but Reagan’s policies never achieved what he had promised. As the historian Gary Wills noted, “Supply-side economics was supposed to promote savings, investment, and entrepreneurial creativity. It failed at all three.” Reaganomics never did serve all Americans. It was never meant to, despite all the promises to the contrary. Working-class Americans without a high school degree saw their weekly wages decrease by 6 percent. Overall, median family incomes, which had steadily risen since the 1940s, began to fall in the Reagan years and would do so for decades afterward. Perhaps the best indictment of the domestic Reagan comes from the Republican strategist and Nixon adviser Kevin Phillips. Reviewing the 1980s, he labeled the decade “a capitalist blowout” that had ushered in a “second Gilded Age.” “By several measurements,” he continued, “the U.S. in the late 20th century led all other major industrial countries in the gap dividing the upper fifth of the population from the lower—in the disparity between top and bottom.” So it remains today, a grim epithet about American “exceptionalism.” Hubris, Restraint and Secrecy: Reagan and the World Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy is difficult to characterize. It had such paradoxes, contradictions and reversals. Reagan was the Cold War super hawk who labeled the Soviet Union an “evil empire” but also the first president to meaningfully decrease the nuclear arsenals of the two superpowers. He was the Iran hawk who talked tough in the Middle East but rarely put American lives at risk and demonstrated diplomatic practicality. He was a president who heavily lauded America and its ostensible democratic values but also funded, armed and supported paramilitary death squads and vicious military juntas. These contradictions raise important questions: If Reagan was so focused on U.S. military potential, then why did so few American servicemen fight and die in combat on his watch? If the Soviets were truly evil, then why open diplomatic channels with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev? If democratic values were so paramount a consideration, then why empower Central American right-wing despots (who were assumed, of course, to be reliably anti-communist)? There are no easy answers, and though it may seem unfulfilling, it must be understood that Reagan’s foreign policy was actually all of these things at once, the hubris and practicality, the militarism and the diplomacy. Improvisation was a key characteristic of Reagan’s foreign policy. As in the domestic sphere, he followed little dogma and proved flexible. Still, a focus on “toughness” and saving face was seen throughout. Reagan entered office on a wave of anti-Soviet hawkishness that he had helped build and encourage. He announced he would end the détente policies of Presidents Nixon, Gerald Ford and Carter and roll back, rather than simply contain, global communism. This was dangerous rhetoric indeed, carrying the possibility to provoke local bloodshed and raise the threat of a general nuclear exchange. Reagan, at almost every turn, chose policies that projected American confidence and power, rather than American values. He seems to have truly despised the communist movements of the world and to honestly have desired the demise of the ideology. However, this doesn’t mean Reagan actually wanted war with the Soviets—he did not. The president didn’t really believe the U.S., or anyone, could win or survive a nuclear war. Nonetheless, he would risk war and rattle the national saber in order to project confidence and demonstrate American will. He entered office with the profound sense that there was “good” and “evil” in a rather binary world and that the U.S. and Soviet Union were on opposite sides of that divide. His profligate defense spending and modernization were a direct provocation and a warning to the Soviets. And the Kremlin genuinely feared Reagan, taking his hyperbolic rhetoric at face value. It was thus that a NATO training exercise, Able Archer 83, caused the Soviets to think they actually were under nuclear attack. Were it not for the sensibility and courage of individual military officers in Russia, the counter-mobilization might have caused a general conflagration. Able Archer was, perhaps besides the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Yom Kippur War, the closest the two superpowers came to nuclear war. Reagan also raised alarm in Russia with his military spending. He spent $2 trillion on defense during his presidency, a 34 percent increase over the already rising Carter budgets. He called for a 600-ship Navy, reinstated development of the B-1 bomber, secured funding for the B-2 bomber, and new cruise missiles. He also enthusiastically backed his Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI)—mocked as “Star Wars” by opponents—a harebrained, probably fantastical scheme to use lasers and other technological means to intercept and destroy Soviet nuclear missiles. Even though many scientists firmly believed Star Wars to be ineffective, Reagan pressed on. And, when American Sovietologists explained that SDI could actually increase the threat of war by convincing the Soviets that the U.S., now able to defend itself, might seek a first strike, Reagan pressed on anyway. Even when it later spoiled near deals on nuclear disarmament and détente with Gorbachev, Reagan would not relent. Unlike Presidents Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson, Reagan sought to turn back the communist tide without the intervention of major American military forces. His Reagan Doctrine, such as it was, stipulated that the U.S. would back anti-communist insurgencies and uprisings the world over, especially in nearby Latin America. These proxies, when armed and funded, would do America’s dirty work to check the Soviets. Reagan would thus fight Soviet proxies in Afghanistan and Angola and across Central America. Nevertheless, with two exceptions—Lebanon and Grenada—Reagan did not expose U.S. soldiers to much combat or danger. Neither was a very prudent or necessary intervention and likely caused Reagan to avoid interventions in his second term. When he sent U.S. Marines into the maelstrom of Lebanon’s bloody sectarian civil war, it was unclear what they were supposed to accomplish. However, once American air and sea power began to intervene on certain sides of the multifaceted conflict, U.S. servicemen became targets for attack. For years after, Hezbollah militias would take American hostages in Lebanon whenever possible. In such a climate an Iranian-backed Hezbollah militia would bomb the U.S. Embassy and Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983, killing hundreds of American Marines and diplomats. Reagan didn’t even know how or against whom to respond, and in a surprising, but sensible, move quietly withdrew the Marines offshore to their ships. A Democratic president would undoubtedly have been portrayed as weak for withdrawing, but Reagan’s hawkishness was such that he faced little backlash. The tiny island of Grenada posed absolutely no threat to the U.S. but—two days after the Marine barracks bombing—Reagan decided to invade and overthrow its new left-leaning government. The official explanation was that Grenada’s new government was building military airstrips for Cuba or the Soviets and that due to the recent coup somehow a few hundred American medical students were at risk. Of course they were not, and Grenada vociferously guaranteed their safety throughout the crisis. What the rapid—but surprisingly clumsy—military victory did do was build confidence in America’s military, helping to overcome the embarrassment and caution induced by Vietnam. Thus, the military doled out thousands of medals and patriotic fervor rose in the United States. Image, as always, was everything. The United States would also arm and back paramilitary death squads in Nicaragua to fight an elected leftist government, and the U.S. would back a right-wing junta in El Salvador known to kill progressive priests and nuns. The Nicaraguan counterrevolutionaries, known as the Contras, would murder hundreds of thousands, including women and children, throughout the 1980s. One of Reagan’s National Security Council consultants admitted that “Death Squads are an extremely effective tool, however odious, in combating revolutionary challenges.” Reagan seemed to have a genuine hatred for Nicaragua’s Sandinista-controlled government. His determination to back the Contras would lead to his administration’s biggest scandal. One thing that did unite Reagan’s foreign policy was his penchant for secrecy and the use of proxy forces rather than conventional military forces. Congress, still shaken by the Vietnam War, had no stomach for an American war in Nicaragua. Thus, in the Boland Amendment, did Congress forbid any aid to the Contras or deployment of military advisers. However, key members of Reagan’s team, especially in the National Security Council, persisted. Though Reagan later denied any direct knowledge, America would eventually illegally, and secretly, sell weapons to Iran (even though Washington backed Iraq in the ongoing war between the two Middle Eastern powers) to encourage the release of American hostages held by Iran’s Hezbollah proxies in Lebanon and route the profits through Israel into the hands of the Contras. This was strictly illegal and potentially particularly embarrassing since Reagan had repeatedly declared he would never negotiate with terrorists. Furthermore, it was certain to upset Iraq, which Reagan and Carter before him had long supported in its war with Iran. Had another politician, especially a Democrat, been in the Oval Office, what came to be called the Iran-Contra scandal may well have ended in impeachment. But Reagan was popular and notionally hawkish and also inspired loyalty in his subordinates. The NSC officials who carried out the policies swore to investigators that they had acted in what they saw as the national interest and had taken care not to involve the president. Adm. John Poindexter, the national security adviser, testified, “We kept him [Reagan] in ignorance so that I could insulate him from the decision and provide some future deniability for the president if it ever leaked out.” In the end, few of those implicated in Iran-Contra would be punished, and Reagan’s successor, President George H.W. Bush, would pardon those who were. Reagan denied any knowledge of the actions that generated the scandal. There was no smoking gun, but it stretches the imagination to believe that Reagan truly had no involvement. Indeed, in a secret memo to Poindexter, Reagan had written, “I am really serious. If we can’t move the Contra package before June 9, I want to figure out a way to take action uni-laterally to provide assistance.” Reagan, for his part, claimed not to remember key facts and not to know about the arms-for-hostages program. His daughter Maureen would later assert that “[w]hat he doesn’t remember is whether he said yes the day before it was done [the Iran-Contra deal] or was told it was done yesterday, and that’s the only thing. He cannot remember and there are no notes on that.” Part of the reason there were no notes is that NSC staffers had pre-emptively destroyed thousands of related documents. Iran-Contra ultimately hurt Reagan’s popularity, but it didn’t meaningfully change his policy or seriously tarnish his legacy. In Iran, in Central America and in Africa, Reagan’s purported democratic values clashed with the reality of American policy. To get a sense of the gap between Reagan’s rhetorical picture of America as a “shining city upon a hill” and the reality of his anti-communism in geopolitics, one need only look to South Africa. The president vetoed an attempt by Congress to impose economic sanctions on the brutal, white supremacist apartheid regime. South Africa, after all, was fiercely anti-communist, so its human rights record was beside the point for Reagan. Congress finally overruled his veto in 1986. Many African-Americans would never forgive Reagan for his support of South Africa. Still, neither hubris nor bumbling singularly characterized Reagan’s policy. There was never enough consistency for that. He was neither all hawk or all dove. His flexibility was best demonstrated in his remarkable second-term turnaround on relations with the Soviet Union. Much of the credit for reduced tensions and increased engagement between the two superpowers must ultimately lay with Gorbachev, then the new Soviet premier. Independent of Reagan’s threats, increased defense spending and proxy wars, Gorbachev realized the need for reform of the Soviet economy and society. He called for greater political openness and greater economic liberalization. He even eased the Soviet grip on the satellite states in Eastern Europe. Both Gorbachev and Reagan wanted to end the Cold War, but it was Gorbachev who made it possible. He inaugurated such a change in the Soviet Union that he presented Reagan the perfect partner. Thus Gorbachev deserves most of the credit. Nonetheless, it was Reagan who had to choose, against the advice of most of his advisers and intelligence agencies, to actually engage and partner with Gorbachev. He did so with an enthusiasm that surprised nearly all observers. The breakthroughs were significant in the course of Reagan’s three summits with Gorbachev, encouraging a Cold War thaw and the first ever actual reduction in each side’s nuclear arsenal. During their second meeting, in Iceland, Reagan’s advisers were horrified and shocked by how close the president and the premier came to sealing a deal to eliminate all nuclear weapons. Only Reagan’s insistence on maintaining his Star Wars initiative scuttled additional movement toward a total disarmament deal. Perhaps only a hawk like Reagan could have gotten away with such compromise and diplomacy, and just as “only Nixon could go to China,” only Reagan could explore peace with the Soviets. Either way, Reagan deserves credit for this volte-face. All in all, Reagan’s foreign policy was improvised, inconsistent and contradictory. Reagan the hawk must bear the responsibility for hundreds of thousands of lives lost in American-backed proxy wars. Still, Reagan the restrainer—unlike Truman, John Kennedy and LBJ—largely avoided costly conventional military conflicts. Reagan the spendthrift would shower money on the Pentagon. Still, Reagan the deal-maker would repeatedly choose diplomacy over war with the Soviets. Reagan the triumphalist would unnecessarily and somewhat farcically invade the tiny island of Grenada. Still, Reagan the pragmatist would quietly retreat from an ill-advised intervention in Lebanon. Reagan’s contradictions could be viewed, alternately, as his downfall and his saving grace in global affairs. His was an administration of tough talk, posturing and anti-communist adventuring, but it was also one of restraint, compromise and flexibility. Reagan the statesman should be neither canonized nor dismissed. He proved, as would many succeeding presidents, that an American leader could on the one hand be a peaceable deal broker and on the other hand be a war criminal. (The latter characterization has been applied to Reagan by some scholars, analysts and foreign and domestic foes for several reasons, including aggression against Grenada in violation of the Geneva Conventions, an allegedly illegal attempted assassination of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, and causing the deaths of countless innocents by illegally supporting Contra death squads.) There are few binaries, and almost no dogmatic certainties, in American foreign policy. Reagan was living proof. * * * America remains a center-right country when compared with other Western nations. It was Reagan who moved the definition of acceptable conservatism toward the right. There could have been no President George W. Bush, and thus no Iraq War, without Reagan. There could be no President Donald Trump without him. Reagan normalized the abnormally right-wing agenda he championed and created the space for conservative populists to ultimately hijack the GOP in later years. Reagan the legend has proved more persistent than Reagan the man. So powerful, so popular and so canonical is the memory of his presidency that even Democratic President Barack Obama would fess up to having admiration for the once-seen-as-radical Reagan. Lost in today’s Reagan nostalgia is the hard truth that his deregulation, social benefits cutbacks and spendthrift defense budgets ensured that the U.S. would fall ever further behind other industrialized nations on key indices of health, education and income equality. Reagan’s optimism, bordering on the delusional, set the tone for decades of unsustainable fiscal policy. Indeed, Reagan, defying the Republicans’ historical restraint on budgets, was the first in a long line of GOP executives who ran up immense deficits and exploded the national debt. Nevertheless, Reagan and his successors rarely paid any political price for this and other counterintuitive policies. On a range of issues, from the economy to culture to national security, Reagan Republicans seemed cloaked in Teflon, immune to injury. Never-ending proxy war, never-ending debt and an ever-widening income inequality—all of these germinated in the Reagan wave of 1980. So much so, in fact, that when the party tacked ever farther right in the intervening decades, the 40th president would appear moderate, or even liberal, on these and other issues. Many academics and liberals would consider such an analysis to be inherently factual. But that misses the point. The American people, by and large, don’t care. They relish fantasy, suspend reality and avoid hard choices whenever the opportunity is presented. Jimmy Carter told Americans harsh truths—for example on energy policy—and called for individual belt-tightening and self-restraint. Reagan, on the other hand, told the populace that it could have it all, the biggest and best of everything: limitless growth, credit, military power and consumable fossil fuels. It doesn’t matter if Carter was “right” on some of these issues. He lost. In that sense, the very fact of Reagan’s victory is the story. Americans got a Reagan and later a Bush, Bush II and a Trump because these men, as presidential hopefuls, adhered with the populace’s desires more than its objective realities. Reagan reflected as much as affected the national mood. He was America’s candidate, America’s president. And, if unchecked, his political descendants may well be America’s demise. * * * To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

Source URL |