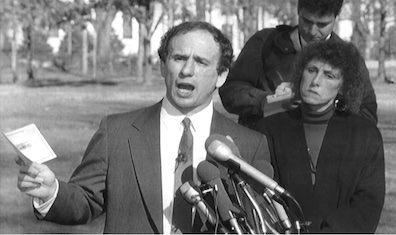

[As factions of the U.S. political elite grapple with the waning days of the Trump presidency, one cannot help but be left with a sense of irony. From election meddling—whether it be legalized bribery (lobbying), disenfranchisement and gerrymandering at home—to lethal interference abroad, including violent regime-change operations, war and other overt and covert assaults on foreign soil, the U.S. elite, capitalist class under Republican and Democratic banners engage in similar and often worse heinous activities on a regular basis. While front-line soldiers are often tormented for decades by the horrors they experience in endless wars conducted by the U.S. government—not to mention the hundreds of thousands who have been maimed and/or lost their lives—the political elite in the U.S. is not known to suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) because they are, perhaps in their own minds, too far removed from the scene. The events of January 6 seem to have left factions with a taste of their own medicine. Notwithstanding, newly-elected president Biden characteristically does not appear to be haunted by any of his past actions; rather he is often boastful about policies that caused great misery. In this exclusive series of articles reviewing Biden’s positions on U.S. foreign policy, Kuzmarov focuses on some of the skeletons in Biden’s political closet. When Biden first campaigned for the Senate in 1972, he positioned himself as a dove who opposed the Vietnam War and even supported a bill that called for banning all covert operations. However, converging with elite political winds of the time, Biden morphed into a neoconservative hawk. After getting a medical deferment from the draft, he derided anti-Vietnam War protestors at Syracuse University and subsequently told the Senate Intelligence Committee in 1976 that he had “no illusions about Soviet intentions and capabilities in the world.” Further, he agreed with Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) that “isolationism was a dangerous and naïve foundation upon which to rest our foreign policy or the intelligence community which must serve that policy.” These statements were not surprising considering that one of Biden’s chief political mentors was W. Averell Harriman, the coordinator of the Marshall Plan and father of the Cold War.[1] By the 1980s, Biden supported increases in intelligence and counterintelligence funding after Jimmy Carter had tried to cut the CIA’s staff by one-third. After the Reagan administration’s invasion of Grenada and bombing of Libya, Biden stated “[Reagan] did the right thing” and “there can be no question that Gaddafi has asked for and deserves a strong response like this,” respectively. In the 1990s, Biden was a chief proponent of the war in the Balkans, and in 2002 played an important role in building Senate support for the preemptive war on Iraq. In Biden’s own words, he proclaimed that he is a liberal only when it comes to civil rights and civil liberties; on other issues, he said “I’m really quite conservative.”[2] Our aim in this series is to shed light on some of the corrupt, murderous and failed foreign policies Biden has backed—all of which may give an indication of what we can expect from a Biden presidency. We hope ultimately to inspire people to work for political change from the grass roots up.— CovertAction Editors] Part 1: The Forgotten Story of How Joe Biden Helped Ramp Up the War on Drugs in Colombia President-elect Joe Biden is not known for being either tight-lipped or humble. Throughout his long political career, he has often divulged information or bragged about things that were in reality quite shameful. A good example is Plan Colombia, a $1.3 billion anti-drug program initiated by the Clinton administration in 1999, which Biden boasted last January about being the “guy who put it together [as head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee].”[3]

In a New York Times op-ed five years earlier, Biden credited Plan Colombia with helping to “transform Colombia in the realm of security, governance and human rights,” and “preventing it from becoming a failed state”[4]—a theme which Biden promoted again in an October 2020 article in the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo. Biden’s assessment does not match the reality for most Colombians. From the time of Plan Colombia’s implementation through the present, the Colombian army, funded and emboldened by the United States, has killed thousands of civilians, falsely claiming that many were guerrillas killed in what became known as the “false positives” scandal. During the same period, more than seven million Colombians have been displaced. “These human costs were never part of the policy calculus for Joe Biden,” said John Lindsay-Poland, author of a seminal book on Plan Colombia.[5]

Plan Colombia built off earlier American counter-narcotics programs, which were heavily militarized in their approach. These programs were designed not only to fight narco-traffickers but also to assist in the Colombian government’s long war against the leftist Fuerzas Armada Revolucionario de Colombia (FARC) guerrillas. Stan Goff, a former Special Forces officer in Colombia, stated that “you were told, and the American public was being told, if they were told anything at all, this was counter-narcotics training. The training I conducted was anything but that. It was pretty much updated Vietnam style counterinsurgency doctrine. We were advised that this is what we would do, and we were further advised to refer to it as counter-narcotics training should anyone ask.”[6]When the Office of Management and Budget proposed taking $100 million out of Plan Colombia for the treatment of U.S. addicts, President Bill Clinton’s drug czar, retired General Barry McCaffrey, made sure it was nixed. Instead, $400 million dollars was appropriated for the purchase of 30 Black Hawk helicopters, made by United Technologies of Connecticut [now part of Raytheon Co.], and $144 million for training and equipping two new anti-narcotics battalions. More than 75,000 Colombian soldiers were also trained at U.S. military academies under the plan. In addition, laser-guided bombs were provided to go along with real-time intelligence used to locate, bomb and kill FARC leaders who were accused of being narco-traffickers.[7]

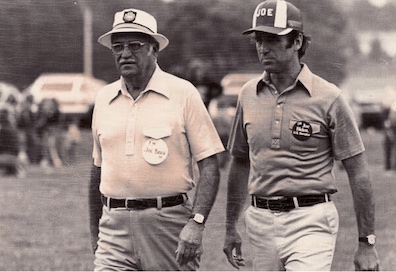

Biden, the War on Drugs and Plan Colombia Biden played a key role lobbying for Plan Colombia in the Senate, where he invoked the age-old—albeit tweaked—U.S. imperialist doctrine: “in the interests of our children and the interests of the hemisphere … to give them [Colombia] a fighting chance to keep them from becoming a narco-state.”[8] Biden’s support for the War on Drugs went back to his first campaign for the U.S. Senate in 1972, when he saw that he could please crowds with tough talk. In one rally, Biden proclaimed that, “when we find the pusher, we must deal more severely with him than with any other element of the criminal society. There should be no mercy.”[9] Once elected, Biden called for greater pressure on Turkey and Southeast Asia to stop poppy cultivation and to use spy satellites to search out heroin supplies.[10]

The product of a middle-class upbringing in the 1940s and 1950s, Biden had always been hostile to the 1960s counter-cultural movement, which embraced marijuana and other mind-altering drugs as a form of societal rebellion. Biden admitted that, “by the time the [1960s] movement was at its peak, I was married, I was in law school, I wore sports coats. You’re looking at a middle class guy…. I’m not big on flak jackets and tie dyed shirts.”[11] In the 1980s, Biden embraced the War on Drugs with as much zeal as drug war guru Ronald Reagan. As chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, he helped pass two bills establishing mandatory minimum sentencing for drug offenses, and another that expanded penalties for marijuana production and trafficking, and which gave federal agents nearly unlimited powers to seize assets from private citizens.[12] Further, Biden co-authored two anti-drug abuse acts in 1986 and 1988 that imposed stricter sentencing for crack cocaine compared to powder cocaine and bolstered prison sentences for drug offenders.[13]

One of Biden’s campaign ads from the era characteristically called drug dealers “potential killers” who should be tracked down “like we track down killers.”[14] The drug trade in his view was as much a threat to the international security of the U.S. as “anything the Soviets are doing,” and should be treated as a “national defense problem,” requiring military solutions.[15] Biden’s support for Plan Colombia followed from this latter position. In April 2000, Biden traveled to Colombia and met with its president, Andrés Pastrana, and the U.S. ambassador to Colombia, Curtis W. Kamman, while observing military operations in southern Colombia. Biden then prepared a report to the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in which he urged Congress to “quickly approve President Clinton’s request for supplemental funding” on the grounds that Colombia was “the source of many of the drugs poisoning our people.”[16] This language was reminiscent of the inflated rhetoric pioneered by Harry J. Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) from 1929-1962, that fueled the growth of America’s War on Drugs. Biden’s report specified that the “security crisis in Colombia warranted U.S. counter-measures” and that “guerrilla fronts had a heavy presence in Southern Colombia and significant role in protecting drug trafficking operations,” which the U.S. needed to stop.[17]

Effects of Plan Colombia In practice, Plan Colombia did little to mitigate drug-related corruption or stop the drug traffic, as Biden has claimed. A December 2020 report released by Eliot Engel (D-NY), the outgoing chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, specified that Plan Colombia was a “counter-narcotics failure,” though it was a “counterinsurgency success.”[18] This latter claim is dubious if we consider the human rights atrocities carried out by military and police forces that were empowered by U.S. military assistance. Engel’s report though brings to light the previously suppressed fact that the central aim of Plan Colombia was to combat the FARC. FARC were branded as narco-guerrillas beginning in the 1980s, even though they were not directly involved in cocaine processing or trafficking but taxed coca profits in their domain. In fact, the major drug-trafficking cartels were primarily allied with the government against FARC, whose ideology they deplored since the FARC advocated for land redistribution.[19] Colombian army officers worked intimately with Carlos Castaño, Colombia’s chief paramilitary leader and a reported CIA asset. Castaño stated that 70 percent of the income for his group called the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), a de-facto wing of the Colombian army which carried out 70-80 percent of noncombat killings, came from drugs. Castaño was close with the powerful Henao-Montoya drug-trafficking cartel and was indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice in September 2002 and charged with trafficking more than 17 tons of cocaine.[20] The AUC had been placed on the State Department’s list of terrorist organizations because of its role in the August 1999 assassination of TV host Jaime Garzón, who advocated for peace with leftist guerrillas.[21] The AUC was also implicated in the murder of dozens of trade union activists at the behest of wealthy ranchers and managers of U.S. corporations, such as Drummond Co. of Alabama, which helped transform Colombia into the world’s fourth largest coal exporter. Biden’s report to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee acknowledged the problem of paramilitaries but emphasized that the human rights climate could only be improved if Plan Colombia were extended. Biden was particularly supportive of aid to the Colombian national police, which in 2004 was tied to one of the largest U.S. drug trafficking indictments in history when a police Colonel, Danilo González, was accused of being an enforcer for the North Valley drug cartel.[22] In the ten years after Clinton left office, the U.S. government spent $10 billion for counter-narcotics under Plan Colombia, which Biden continued to endorse as Vice President. Yet in 2016 Colombia remained the “world leader in coca production.”[23]

Senator Paul Wellstone (D-MN) had promoted an alternative to Plan Colombia in 1999 that would have switched $225 million from military aid to drug treatment programs at home. He argued that “we’ve been down this road forever, forever,” and that “more soldiers and more guns have not and will not defeat the source of illegal narcotics.” Biden rose immediately to President Clinton’s defense in the Senate, stating that Congress would “wreak a whirlwind” if Plan Colombia “failed to strike back at the drug traffickers,” and that Colombia’s President Andrés Pastrana was the “real deal.”[24] Colombia’s leading newsweekly, Semana, denounced Pastrana, however, for “going along, after obvious pressure, with the opportunism and hypocrisy of U.S. officials,” and accepting U.S. “aid” which was a “recipe for destruction, indefinite war and indebtedness.”[25] His successor, Álvaro Uribe Vélez (2002-2010), was listed in a DIA report as a Medellín cartel collaborator and has been under house arrest while the country’s Supreme Court investigates his role in helping to create illegal paramilitary death squads with his brother Santiago, among other crimes.

In a classic essay in CovertAction Magazine, from the Spring/Summer 2000 issue, journalist Mark Cook observed that U.S. policy in Colombia in the 1990s was run by a remarkable number of veterans of the dirty war in El Salvador in the 1980s. Examples included Under-Secretary of State for Political Affairs Thomas Pickering, who had justified mass killings of civilians as ambassador to El Salvador in 1984, and Assistant Secretary of State Peter Romero, who believed that the “Salvador solution” could be the model for Colombia.[26] The “Salvador solution” entailed paramilitary and death-squad activities and state-sanctioned terrorism.[27] Biden knew all about this as he had backed money and training for El Salvador’s death squads in the 1980s. Despite mostly opposing Reagan’s foreign policy in Central America, Biden said there was a “need to send U.S. military equipment to the region [Central America].”[28] Besides El Salvador, Colombia in the early 21st century also came to resemble Vietnam, with the presence of foreign military advisers, high-tech listening posts, aerial defoliation, river boats, and helicopter assaults on the countryside.[29] Chemical Warfare One of the lesser-known and worst aspect of Plan Colombia was the aerial defoliation program, which drove villagers away from FARC-controlled areas and made way for mega-projects benefiting multinational corporations.

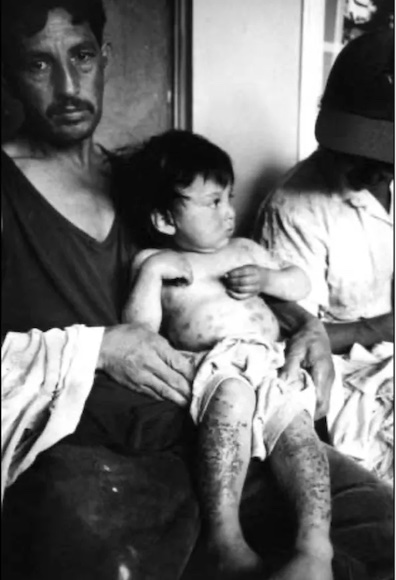

Glyphosate or Roundup weed killer, manufactured by Monsanto, one of the companies responsible for manufacturing Agent Orange used in the Vietnam War, was sprayed at one hundred times the concentration which was allowed in the United States. Though the State Department claimed that it was no more toxic than “common salt, aspirin or caffeine,” a 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) study found that glyphosate “probably causes cancer.”[30]

Gonzalo de Francisco, a Colombian national security adviser, likened the fumigation program to “chemotherapy” as sometimes “you end up killing the patient.”[31] Elsa Niva, a Colombian agronomist with the Pesticide Action Network, reported that in two months alone 4,289 Colombians suffered skin or gastric disorders from the chemical spraying while 178,377 creatures were killed, including cattle, horses, pigs, dogs, ducks, hens and fish.[32] An unknown number of farmers died from dehydration, fever and other sicknesses, and thousands were displaced—an outcome known in advance as the initial Plan Colombia package backed by Biden included $15 million for “emergency resettlement and employment of persons displaced by the Push into Southern Colombia program.”[33] Journalist Hugh O’Shaughnessy visited the indigenous Cofän community of Santa Rosa de Guamuez, whose pineapples were stunted and shriveled because of the chemical spraying and once-green banana plants were no more than blackened sticks. The children were underweight, suffering from respiratory problems and stomach pains.[34] A local health worker in Putumayo, where thousands of villagers were displaced, recalled how the spraying turned “everything yellow; not a green leaf on a tree. Many jungle animals dead, dead monkeys, dead birds, fish farm tanks with thousands of dead fish floating in them.”[35] In a class action lawsuit, a group of farmers alleged that DynCorp of Falls Church, Virginia—a CIA-connected company, which was awarded a five-year, $170 million contract to carry out the fumigation—caused severe health problems (high fever, vomiting, diarrhea, dermatological problems) and the destruction of food crops and livestock of approximately 10,000 residents in the region bordering Ecuador. Further, the toxicity of the fumigant caused the deaths of four infants—facts Biden has of course ignored.[36] Pirates Who Benefited The primary beneficiaries of Plan Colombia were large defense contractors, which provided Biden’s campaign over $436,000 more than Trump’s during the 2020 presidential election campaign.[37]

At the time of Plan Colombia’s passage, a congressional aide stated that “every pirate, bandit—everyone who wants to make money on war—they’re in Colombia.”[38] These pirates included Monsanto, Bell and Sikorsky, which manufactured Black Hawk helicopters, and the CIA-connected energy giant Enron, which owned Centragas, a 357-mile natural gas distribution system in northern Colombia. Another of the pirates was Los Angeles-based Occidental Petroleum—which held controlling interests in the Cano-Limon Convenas oil field and pipeline running from the Venezuelan border. Vice President Al Gore, who supported Plan Colombia with Biden, happened to have more than $500,000 worth of family stock in Occidental, which contributed at least $250,000 to the Clinton-Gore ticket.[39] The company’s founder, Armand Hammer, had been a key benefactor of Gore’s political career, along with that of his father, Senator Al Gore, Sr.[40] During the 2020 campaign, Occidental gave $12,765 to presidential candidate Joe Biden, perhaps in part as a reward for his support for Plan Colombia.[41] In June 2001, a Colombian court heard how a U.S. security firm working for Occidental had played a fatal role in an ill-starred army raid against FARC, “directing helicopter gunships that mistakenly killed eighteen civilians.”[42] This was a great example of the nexus between large corporations, the Colombian army, U.S. intervention, and human rights abuses—which were intensified under a policy that the new so-called “liberal” president is proud to have helped put together. What to Expect from President Biden If the past is any indication, Biden will likely sustain the U.S. drug war and extensive aid program in Colombia, which reached $448 million in 2020, the highest in nine years. On the campaign trail, Biden characterized Colombia as the “keystone” of U.S. policy in Latin America. This is in spite of Colombia’s rightward drift under President Ivan Duque (2018-present), a protégé of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, who has taken measures to undermine a 2016 peace deal with FARC. Human rights groups reported 68 massacres by the Colombian army in the first three quarters of 2020, mostly targeting ex-FARC commanders and regional Afro-Colombian leaders. Colombia’s strategic significance is accentuated by the presence of seven U.S. military bases and the political crisis in neighboring Venezuela, where Biden has recognized the right-wing renegade regime of Juan Guaidó, and labeled socialist President Nicolás Maduro a “dictator plain and simple.” The latter language makes clear that Biden will go forward with regime-change operations that rely on strong bilateral relations with Colombia, irrespective of its abysmal human rights record. Notes: [1] Joe Biden, Promises to Keep (New York: Random House, 2008), 248. [2] Evan Osnos, Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now (New York: Scribner, 2020), 42. [3] John Washington, “We Need to Reverse the Damage Trump Has Done in Latin America. Biden’s Plans Don’t Cut It,” The Intercept, April 18, 2020. [4] Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “A Plan for Central America,” The New York Times, January 29, 2015.` [5] Washington, “We Need to Reverse the Damage Trump Has Done in Latin America.” [6] Douglas Stokes, Terrorizing Colombia: America’s Other War (London: Zed Books, 2005), 90. [7] John Lindsey Poland, Plan Colombia: U.S. Ally Atrocities and Community Activism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 89, 93; Peter Dale Scott, Drugs, Oil and War: The United States in Afghanistan, Colombia and Indochina (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 73; Noam Chomsky, Rogue States: The Rule of Force in World Affairs (Boston: South End Press, 2000), 80. Originally, Plan Colombia was meant to complement economic aid from the European Union (EU), but amidst pressure from Colombian human rights groups and NGOs, the EU pulled back because it disapproved of the U.S. military approach. [8] Max Blumenthal, “Joe Biden Fueled the Latin American Migration Crisis,” Consortium News, July 31, 2019. [9] Quoted in Branko Marcetic, Yesterday’s Man: The Case Against Joe Biden (London: Verso, 2020), 18. [10] Marcetic, Yesterday’s Man, 74, 75. Many Democrats at that time were advocating for stronger measures to combat the international drug traffic, in part to offset the addiction of American soldiers in Vietnam. See Jeremy Kuzmarov, The Myth of the Addicted Army: Vietnam and the Modern War on Drugs (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009). [11] Marcetic, Yesterday’s Man, 67. [12] Chris Calton, “How a Young Joe Biden Became the Architect of the Government’s Asset Forfeiture Program,” Foundation for Economic Education, March 9, 2019; Nicholas Fandos, “Joe Biden’s Role in ’90s Crime Law Could Haunt Any Presidential Bill,” The New York Times, August 21, 2015. [13] Jack Delaney, “Jim Crow Joe: Biden’s Record on Race,” Counterpunch, December 6, 2020. [14] Marcetic, Yesterday’s Man, 75. [15] Marcetic, Yesterday’s Man, 76. [16] Joseph R. Biden, Jr. “Aid to ‘Plan Colombia’: The Time for U.S. Assistance Is Now,” A Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, by Joseph R. Biden, Jr., 106th Congress, May 2000 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002). [17] Biden, “Aid to ‘Plan Colombia.”” [18] Report of the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission, December 2020. [19] See Robin Kirk, More Terrible Than Death: Drugs, Violence and America’s War in Colombia (New York: Public Affairs, 2004). [20] Scott, Drugs, Oil and War, 74. Castano’s brother, Fidel, with whom he formed his death squad, amassed a fortune as a drug dealer in league with Pablo Escobar. Mark Cook, “U.S. Intervention in Colombia and Ecuador,” CovertAction Quarterly, Spring-Summer 2000, 28. [21] “Who Killed Jaime Garzón? Document Points to Military/Paramilitary Nexus in Murder of Popular Colombian Comedian,” September 29, 2011, The National Security Archive, George Washington University. [22] Erin Rosa, “Fumigation of Coca Crops Still a Booming Business in Colombia,” The Narco News Bulletin, November 2, 2010. [23] Winifred Tate, “No Peace For Colombia,” North American Congress on Latin America, February 24, 2016. In 2019, a new record of 212,000 hectares of coca were cultivated in Colombia. [24] David Rogers, “Antidrug Plan Passes a Test in the Senate,” The Wall Street Journal, June 22, 2000, A6. Senator Gorton (R-WA) promoted an amendment to slash the Plan Colombia package from $934 million to $200 million. A copy of Biden’s speech is available here. [25] Mark Cook, “U.S. Intervention in Colombia and Ecuador,” CovertAction Quarterly, Spring-Summer 2000, 28; Stokes, Terrorizing Colombia, 92; Adrian Alsema, “Colombia’s Former President Admits Having Flown on Jeffrey Epstein’s Lolita Jet,’” Colombia Reports, August 14, 2019. [26] Mark Cook, “The ‘Salvador Boys,’” Covert Action Quarterly, Fall-Winter 1999, 18, 19. [27] See Greg Grandin, Empire’s Workshop: The U.S., Central America, and the Rise of the New Imperialism (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2005). A Truth Commission found that Salvadoran government forces were responsible for 93 percent of atrocities in El Salvador’s civil war. [28] Marcetic, Yesterday’s Man, 139. [29] Scott, Drugs, Oil and War, 99. [30] Cornelius Friesendorf, US Foreign Policy and the War on Drugs: Displacing the Cocaine and Heroin Industry (New York: Routledge, 2007), 132, 134; William Neuman, “Colombia May Halt an Anti-Drug Program,” The New York Times, May 15, 2015; Gary Leach, Beyond Bogota: Diary of a Drug War Journalist in Colombia (Boston: Beacon Press, 2009), 78. [31] Sean Donahue, “Rand Beers and Colombia,” in Dime’s Worth of Difference: Beyond the Lesser of Two Evils (Oakland, CA: AK Press/Counterpunch, 2004), 253, 254. [32] Hugh O’Shaughnessy, “Colombia: Chemical Spraying of Coca Poisoning Villages,” The London Observer, June 17, 2001. [33] Poland, Plan Colombia, 53; Biden, “‘Aid to Plan Colombia..’” [34] Hugh O’Shaughnessy, “Colombia: Chemical Spraying of Coca Poisoning Villages.” The London Observer, June 17, 2001. [35] Winifred Tate, Drugs, Thugs and Diplomats: U.S. Policy-Making in Colombia (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2015), 198, 199. [36] “DynCorp lawsuits (re Colombia & Ecuador)”. [37] Seee here. [38] Pedro Ruz Gutierrez and E.A. Torriero, “Military Contractors Line Up For U.S. Drug War in Colombia,” The Chicago Tribune, September 24, 2000. [39] Poland, Plan Colombia, 58, 59; Tony Koran, “Gore’s Big Oil Connection: An ‘Occident’ of Birth?” Time, September 25, 2000. Occidental CEO Ray Irani spent two nights in the Lincoln bedroom after giving a $100,000 donation. Occidental expected a payoff from the granting of exploration rights to a newly discovered oil field called Boqueron which was expected to yield more than 300 million barrels. Enron had given a huge amount of money to the Democratic Party additionally. [40] On Hammer, see Steve Weinberg, Armand Hammer: The Untold Story (New York: Random House, 1990). [41] www.opensecrets.org [42] Oliver Villar and Drew Cottle, Cocaine, Death Squads and the War on Terror: U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011), 11. Source URL |