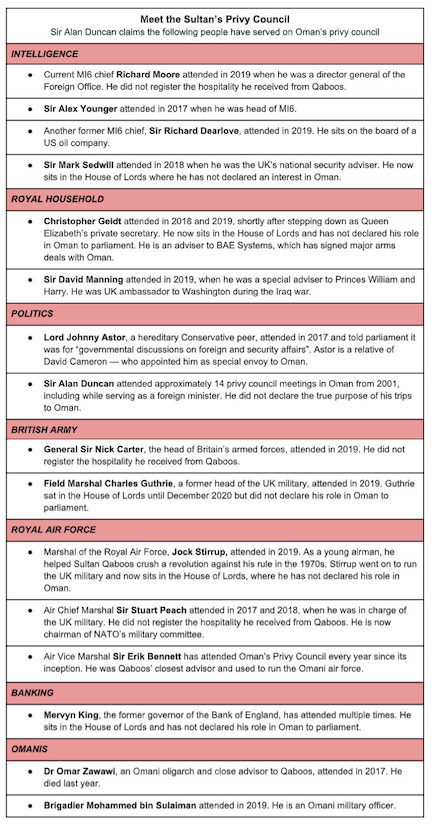

The repressive ruler of a close U.K. ally in the Gulf secretly received decades of advice on security, foreign and economic policy from a group of privy councillors who were drawn almost exclusively from the British establishment, it has emerged. Oman’s dictator, Sultan Qaboos, who ruled the country for 50 years from 1970 to 2020, was advised by a secret privy council right up until his death last year. The scheme appears to have been inspired by Britain’s privy council, the oldest functioning legislative assembly in the U.K., whose members advise the queen and have access to classified intelligence material. Unlike the queen who is a ceremonial monarch, Sultan Qaboos wielded absolute power, banning political parties and independent media. He spent billions of pounds on British weaponry and surveillance equipment to fortify his regime, which is located on a key oil supply route between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Now it has emerged that his top advisers included seven current and former heads of MI6 and the U.K. military, a foreign office minister, a British oil executive, the ex-governor of the Bank of England, a special adviser to Princes William and Harry and one of Queen Elizabeth’s closest aides. Six of the group are members of the House of Lords. None of them appear to have publicly registered their role on Oman’s privy council. The House of Lords code of conduct requires members to register “all relevant interests.” financial and non-financial. Failure to do so can result in referral of the matter to the Commissioner for Standards. Aside from Qaboos himself, only one other Omani would usually attend the privy council meetings, whose existence was concealed from the sultan’s subjects.

Omani exiles in Britain confirmed they had never heard of the sultan’s privy council and told Declassified they were shocked by the revelations. Nabhan al-Hanashi, chairman of the Omani Centre for Human Rights, told Declassified: “Qaboos was always trying to pretend that he was an independent ruler, when in fact he was an agent of the British empire.” He said the new evidence showed that advisers from “a country like Britain, which usually claims to respect human rights and people’s freedom of choice, were involved directly in humiliating the citizens and depriving their rights”. Khalfan al-Badwawi, who was arrested and tortured after participating in Arab Spring protests in 2011, said: “This is proof that British colonialism never ended. Omanis have long suspected that MI6 treats our country like it’s their back garden. These British privy councillors need to get out of Oman.” In addition to the privy councillors, it was already known that Britain has around 90 troops on loan to the Sultan and three GCHQ spy stations are located in Oman. In the last years of his rule, Qaboos also agreed to let Britain build two military bases in the country to project its power in the Middle East. Al-Badwawi added: “It shows we are not only fighting the sultan’s regime. If we are complaining of repression or unemployment in Oman, the U.K. has a role in that. The sultan, with his British advisers, looted the wealth of Oman and we don’t have a say on anything.” Oman, while achieving substantial economic development in recent decades, suffers from high youth unemployment and national debt, with one of the world’s largest defence budgets per capita. The ruling family lives in lavish palaces and owns super yachts. Al-Badwawi commented: “We cannot decide our country’s economics or politics. We don’t have any say about our national debt, but we will have to pay for that in future even if we become a democracy.”

Midnight Meetings It is claimed that every January since the 1990s an elite British group flew into Oman on the sultan’s private jet for secret privy council meetings at midnight in the sultan’s palace. Their sessions were followed by lavish banquets that lasted until 4 a.m. The sultan’s majority-British privy council met as recently as January 2019. Qaboos died 12 months later and it is not known if his successor, his nephew Haitham, has continued the tradition. Oman’s privy council only came to light when the diary of millionaire Alan Duncan, a former Conservative MP, was published last week. He says the privy councillors would spend hours relaxing at the sultan’s palace before the meetings started. Ahead of one session they had: “Lunch beside the pool… On offer is Petrus, Cheval Blanc [expensive wines]… once the clock nears 11[pm] we are suddenly summoned. Our three-hour meeting with the Sultan covers all the topics he has asked for.”

Duncan secretly attended at least 14 sessions of Oman’s privy council from 2001, including while working for the British government as a foreign minister. The ministerial code says “it is of paramount importance that Ministers give accurate and truthful information to Parliament… Ministers who knowingly mislead Parliament will be expected to offer their resignation to the Prime Minister.” Despite these clear instructions, Duncan did not declare in any of his parliamentary or ministerialregisters of interests, travel, hospitality, gifts or meetings that he had attended Oman’s privy council. Instead, he listed his trips to the country as “strategic seminar[s] with the Government of Oman,” sessions on “inter-governmental relations” or saying he was a “guest of the Government of Oman.” Yet in his diary he describes the events explicitly as the “annual Privy Council in Oman, a one-day event at which senior officials from the U.K. give the Sultan privileged briefing on hot topics around the world.” The costs of Duncan’s flights and accommodation, worth thousands of pounds, were paid by the Sultan. Sometimes he received watches, cufflinks or a “traditional Omani coffee pot and incense burner” in reward for his advice. Although Duncan’s diary, In the Thick of It, was serialised in the Daily Mail and reviewed extensively by other media, his revelations about Oman’s privy council have so far received almost no attention. Only The Times has mentioned the issue in passing. Its reviewer, Quentin Letts, wrote: “Overseas contacts are a theme and Duncan’s relationship with MI6 is never clear. How come he, along with senior British defence figures, is on the privy council of Oman? How did he become so close to Oman’s late sultan? Vulgar of one to ask, no doubt.”Several of the British privy councillors were involved in deciding Whitehall policy towards Oman whilst secretly conferring with Sultan Qaboos. The civil service code says that Whitehall staff must not further the interests “of others” by using information acquired in the course of their official duties or “accept gifts or hospitality… from anyone which might reasonably be seen to compromise your personal judgement or integrity.”

The Godfather Connection One little-known name on this list may be the most important. Sir Erik Bennett features heavily in Duncan’s diary, although he was last discussed in a U.K. national newspaper in 1995. Back then, The Sunday Times hinted at the existence of a privy council, describing Bennett as “one of Oman’s (and Britain’s) best-kept secrets: the key figure in a group of elderly former military and intelligence officers who help the Sultan to run his rich, strategically vital country at the mouth of the Gulf.” In January, Declassified revealed that Bennett had continued advising Sultan Qaboos in some capacity until at least 2012, when the pair attended a lunch at Buckingham Palace with the queen and Foreign Secretary William Hague. However, Duncan’s diary provides substantial new information about Bennett, who he says is “my ‘not-quite’ godfather,” which might explain how he came to have such good access to Oman’s leadership. In the early 1990s, Duncan made millions of pounds as an oil trader and advised clients in Oman. He also entered parliament as an MP in 1992 and since 2000 has visited Oman at least 24 times. Prime Minister David Cameron appointed Duncan as a special envoy to Oman in 2014, a brand-new position, and later made him foreign minister for the Americas and Europe. In his diary, Duncan says that despite his ministerial job title limiting him to those geographic regions, he was effectively in charge of U.K. relations with Oman and another Gulf dictatorship, Bahrain, due to his strong “personal relationships” with the rulers of those regimes. Duncan frequently spoke to Erik Bennett by phone or at lunches in London, and wrote letters to Sultan Qaboos about British politics “two or three times a year” to keep “our top-level links in working order.” Stuart Laing, former U.K. ambassador to Oman, also mentioned the importance of both Bennett and the Sultan’s privy council when speaking to a Cambridge University oral history project in 2018. Laing, who served in Oman from 2002-05, said the subject of who advised the sultan was “a little bit sensitive.” To appease nationalist sentiment, Qaboos implemented a process of “Omanisation” in the 1980s to replace figures from the former colonial power with Omani subjects. Laing confirmed, however, that behind the scenes, Bennett organised “what he called, somewhat pretentiously, but what the hell, a ‘privy council,’ ” which advised Qaboos. Laing’s description of the council, taking place late at night around New Year, matches the details in Duncan’s diary. The former ambassador added: “People were giving advice to the Sultan, from top-levels of British business and politics and public affairs and army.” In Laing’s opinion, although Bennett was working for Qaboos, the former RAF officer “was really quite patriotic actually in lots of ways and thought very strongly about British interests” – a comment which again indicates the extraordinary degree of British influence over Oman post-independence. Lavish Parties Another revelation about Oman in Duncan’s diary involves the sultan’s lavish New Year’s Eve parties, which took place days before the annual privy council meetings, with some of the same figures attending both events. In January Declassified revealed that when Qaboos held these parties in the 1990s, they were attended by senior British politicians such as Jonathan Aitken, who was defence procurement minister. Duncan’s diary claims that these parties continued up to 2019, and that he attended them for 20 years. Former senior MI6 officer Alec McDonald, who has published a new book about Oman, says these parties date back to the 1980s.

Little-known is that McDonald was seconded from MI6 to run the Sultan’s vast internal security service from 1985-93. He describes the parties as part of a series of “fairy tale evenings” that British dignitaries would routinely attend in Oman. The New Year parties, according to Duncan, were “not so much a buffet as a sumptuous feast with two lines of tables, each perhaps fifteen yards long, groaning with massive platters of lobster, prawns, chicken, etc. That’s just for starters.” An 8-foot-high New Year cake topped off the dinners at 2 a.m., followed by an orchestra concert. The events combined business with pleasure. At the meal in January 2019, Duncan had “over half an hour of face-to-face conversation” with Qaboos in which he, Duncan, “landed” the idea of a comprehensive “strategic plan for U.K.-Oman engagement… not just a commitment based on defence and security.” The U.K.’s so-called comprehensive agreement with Oman was a “masterplan” Duncan had persuaded British government officials – some of whom were also members of the Sultan’s privy council, such as Sir Mark Sedwill – to accept. It was signed in May 2019, four months after Duncan’s face-to-face meeting with Qaboos, and commits the two countries “to working together in a number of sectors including science, health, technology and innovation.” The full terms have never been published. Duncan’s diary says the agreement also involved revising the “defence guarantee” which Margaret Thatcher made to Qaboos in a letter when she was prime minister in 1983. Declassified has not seen this letter, but last year we published a Ministry of Defence directive from 1981 which said the loyalty of British troops on loan “to the Sultan of Oman must never appear to be in doubt.” It also instructed them to protect the Gulf monarchy “against external and internal threats.” Defence ministers have refused to tell parliament when the directive was last updated. Death of a Dictator While ministers are notoriously secretive about U.K. relations with Oman, Duncan’s diary divulges detail after detail, including Whitehall’s reaction to the death of Qaboos last January — a subject on which Declassified’s freedom of information requests have been denied.

Duncan was aware the sultan’s health was deteriorating a month before his death, saying that “alarm bells are ringing” as he alerted prime minister Boris Johnson by text that “we may all have to fly there at short notice.” Duncan spent New Year 2020 in Oman, “playing a key role in keeping the U.K. government updated [on the Sultan’s health], and ensuring they were ready with the long-planned diplomatic show of respect when the crucial moment came.” Then on Jan. 10, 2020, he received a text from General Stanford, the U.K.’s most senior officer on loan to Oman, saying that “Omani armed forces are on ‘red alert,’” fearing what might happen if the Sultan died. Declassified has previously revealed that Omani armoured vehicles were deployed to the capital, Muscat, to prevent unrest. Stanford texted Duncan throughout the day on the Sultan’s condition, informing him at 1am the next day that Qaboos had died. “There now swung into action the long-prepared plans for the U.K. to send a high-level delegation to pay official condolences,” Duncan notes, as flags were lowered to half-mast on government buildings in the U.K. Despite the forward planning, Duncan complains that the U.K. “spatchcocked together the various flights” and had to “use crappy RAF planes.” Public records show Prince Charles’ flight for the one-night trip to Oman cost the U.K. public £210,000, whilst Johnson’s chartered flight with 10 officials cost a further £143,276. Defence Secretary Ben Wallace spent £4,697. The head of the U.K. military, General Sir Nick Carter, and Duncan – who both attended the Sultan’s last privy council meeting in 2019 – also flew out to offer their condolences, making it a larger delegation than any other country. When Duncan met Qaboos’ successor, Haitham, at the funeral, the new sultan smiled and said, “Hello, my friend.” Duncan commented: “It was a subtle personal courtesy, and very touching. So we banked it… Well done, U.K.. We got there.” Since taking power, Oman’s new absolute ruler, Haitham, has continued to crack down on any dissent. Declassified asked the Foreign Office, MI6, MOD, Cabinet Office and Buckingham Palace whether it was appropriate for their senior staff to secretly advise a foreign head of state without publicly declaring their services. None of them provided a statement responding to our questions. The Oman embassy in London was asked to comment. Source URL |