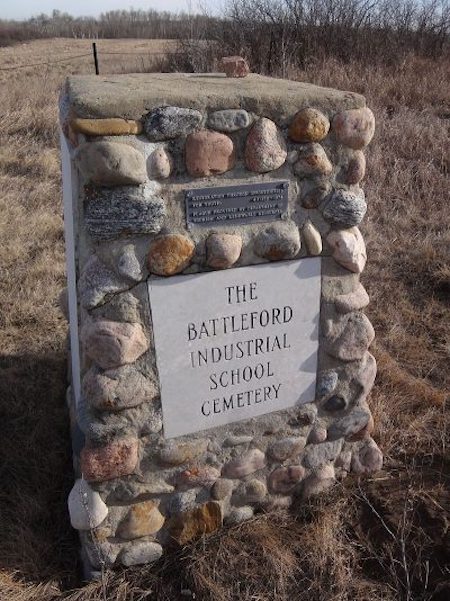

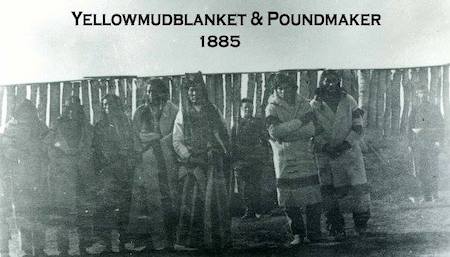

The First Nations of Manitoba chose the right target when they toppled the statue of Queen Victoria in front of the Manitoba Legislature following discovery of the graves of more than 1000 indigenous children around three residential schools. Their action rang bells around the world because what was inflicted upon them in Victoria’s name was also inflicted upon other peoples, often at the same time and at the hands of the same British troops: military conquest, bloody repression, massive settler invasions, and racist domination. The first burial at the Cowessess First Nation cemetery, where 751 graves of young indigenous residents were discovered, occurred in 1885. That was the year of the famous Conference of Berlin at which European powers met to divvy up Africa before they scrambled to colonize it. 1885 is also a watershed year in the history of the British Empire and its new Dominion, British North America, or Canada. It was the year that Empire sealed its third conquest in North America, after the conquest of Quebec in 1759-60 (also known as the Seven Year War or the French and Indian War), and the brutal repression of the Patriots Revolt in 1837-38, which was the equivalent of another conquest. On November 16, 1885, the John A. MacDonald government hanged Louis Riel in the quarters North-West Mounted Police (now the RCMP). The hanging was cheered on by an Orange-Order-dominated Toronto, but was loudly and massively condemned in Montreal, including by Quebec Premier Honoré Mercier. “Louis Riel is my brother,” he said before a crowd said to be close to 50,000. Riel’s crime was to have tried to federate the Métis and the Indigenous nations under a provisional government opposed to the land grab and massive settling of the North-West Territories that the Indigenous people had occupied for millennia. Eleven days later, on November 27, 1885, the same MacDonald Government publicly hanged six Cree and two Nakota warriors at Battleford, Saskatchewan. They are Kah – Paypamahchukways (Wandering Spirit), Pah Pah-Me-Kee-Sick (Walking the Sky), Manchoose (Bad Arrow), Kit-Ahwah-Ke-Ni (Miserable Man), Nahpase (Iron Body), A-Pis-Chas-Koos (Little Bear), Itka (Crooked Leg), Waywahnitch (Man Without Blood).

The largest public hanging in the history of Canada and burial in a common grave followed on hasty trials before an Anglo-Protestant Jury and a judge by the name of Charles Rouleau, who was in flagrant conflict of interest: his house had been burnt during the conflict. To make the message clear, members of the hanged warriors’ nations were forced to attend so that they would never forget. In a confidential letter written seven days earlier, John A. MacDonald wrote: “The executions ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs. This message came in the wake of his declaration that Louis Riel “shall hang, even though all dogs in Quebec bark in his favour.” “Canada’s first war,” as Desmond Morton describes it, was in fact the second military intervention aimed at imposing British sovereignty over the North-West Territories. The first occurred in 1870 and was aimed to eliminate the first provisional government of Manitoba, also led by Louis Riel.

A colonial conquest among many The commander of British Troops sent to put down Riel in 1870 was Marshal Garnet Wolseley. More than a run-of-the-mill British officer, Wolseley was a symbol of the planetary—and bloody—expansion of the British Empire in the 19th century. Named Viscount Sir Wolseley in 1885 by Queen Victoria, Wolseley, before confronting Riel, had earned his colours in the murderous colonial repression in India in 1857 and in China in 1860, including the destruction and looting of the Old Summer Palace in Peking, that “wonder of the world,” as Victor Hugo described it. After Riel, as Governor of the Gold Coast (now Ghana), he headed the British troops that took Kumase, capital city of the Ashanti Kingdom, and he razed it; he led British troops to put down rebellions in Egypt, in Khartoum and in South Africa. Wolseley, an avid supporter of the slavocracy general Robert E. Lee, is still honoured in Canada where streets in Montreal-West, Toronto, Thunder Bay, and Winnipeg bear his name as well as a town in Saskatchewan … just 60 kilometers away from the Cowessess First Nation. In 1885, Major-General Frederick Middleton, another senior British officer and veteran of British colonial wars, headed the troops sent to crush the resistance led by the Métis and the First Nations. Like Wolseley, Middleton was an officer with the British Troops that brutally repressed the Indian uprising in 1857 against the Crown’s agent, the British East India Company. He had also led troops to put down the Maoris in New Zealand. Crushing Indigenous peoples was is specialty. His troops in 1885 consisted of the paramilitary militia known as the North-West Mounted Police, and volunteer militias, mostly Orangemen from Ontario. The British Crown wanted to avoid provoking the most powerful army in the world, the US army, by deploying formally British troops. Without understanding the nature and context of this third British conquest, it is difficult to understand what followed, be it the imposition of the land-grab treaties—coyly referred to as “numbered treaties—the Indian Act or today’s dismal situation in which the Canadian government talks of “reconciliation” while First Nations’ leader demand justice. “Strike at the heart of the tribal system” A characteristic of all conquests is that the conqueror will deploy all means to ensure the conquered peoples don’t rise again. These include deportation (as with the Acadians in 1755 in a prelude to the first conquest), confinement to reserves, subjugation, assimilation, or all of the former.

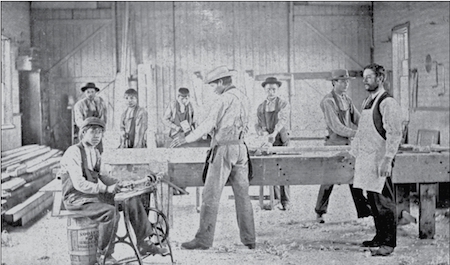

Few have forgotten the hanging of Louis Riel in 1885, but most are unaware of the public hanging of the Indigenous warriors. These hangings are vital symbols in understanding the history of Canada, but they are but the tip of the iceberg of policies implemented by the conquering British Empire and its dominion of Canada. Following Wolseley’s military operations in 1870, the Métis of Manitoba, who until then accounted for about 80 percent of the population, were chased away in what can be described as pogroms. The region was flooded with settlers from Ontario or the “British Isles,” including a large number of Orangemen, who obtained land that was refused to Métis. The land-grab treaties were rapidly inflicted on the First Nations—seven treaties in six years (1871-77) covering the entire territory that was to become Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta—. First nations were made to know that even if the Chiefs refused to sign, the Canadian Government would proceed whether they liked it or not. The Indian Act was adopted in 1876 thereby making the Indigenous people “wards of the state.” This Act invested the Indian Agents—and the NWMP—with powers over the life and death over thousands of First Nations peoples. In 1880, the industrial and residential school policy began to be implemented seriously. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs and Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories at the time was Edgar Dewdney, a favourite of John A. MacDonald’s (he was an executor of MacDonald’s will), and a man “profoundly attached to the empire and the British monarchical tradition,” according to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. From the time he was appointed Indian Commissioner in 1879, Dewdney was determined to “strike at the heart of the tribal system” by quickly opening more residential schools so as to put an end to the agitation of First Nations aimed at gaining more autonomy and improved treaties. This policy worked for many years. The “Little Lottery”: “loyal” or “disloyal“ A few months after Riel was arrested, on July 20, 1885, the Assistant Indian Commissioner and former Indian Agent of Battleford, Hayter Reed, submitted a report with 15 points on “The Future Management of Indians.” He also provided a list of the nations/bands described either as “loyal” or “disloyal” with additional details about the chiefs and members suspected to have been involved in some way in the Resistance. That report became the basis of Canadian policy towards the First Nations for years to come. It touches on everything: exemplary punishment of those who resisted (whence the public hangings); severe collective punishment, including privation of rations (starvation) and other necessities, applied to any and all who, according to the Indian agents, lacked loyalty; confiscation of horses, firearms and tools among those “disloyal” members of a nation or band; confinement to reserves unless in possession of written permission from an Indian agent; all ties between the Métis “Half-breeds” and other First Nations were to be severed and communication was to be forbidden, with the same being applied to “Canadians;” the “good” Indians (loyal) were to be rewarded with “substantial recognition” to confirm their loyalty, the “bad and lazy” ones were to lose their reserve; and more and more. This “Little Lottery” used to control the First Nations after the Riel-led resistance resembles the one used with some success by the British Crown after the brutal repression and hangings of the Patriots in Quebec in 1837-38. The goal was to coopt a certain French-Canadian elite by using political emoluments, rewards, nominations, recognition and other crumbs. That “Little Lottery” succeeded to a certain extent in transforming revolutionary Patriots into very tame collaborators of the new regime set up by the British. What about the churches? In all colonial conquests, churches play an important role in support of the military and political power. They did so in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America and in North America. In the case of British North America, the Anglican Church has always been the Crown’s favourite, as the king or queen was, and is, the Supreme Governor of that Church.

The Catholic Church joined in. It quickly reached an agreement with the British Empire. During the Patriot’s Revolt in 1837-1838 in Lower Canada, the Catholic Church supported the British by refusing Patriots and their supporters the right to be buried in Catholic cemeteries, threatened to excommunicate them, and ordered them to comply with the instructions of the British authorities. The churches were brought in to keep the promise made by the Government of Canada and written in the treaties to provide schools to the First Nations. They were to support a policy devised by and for the conquering power, the British Empire and its Dominion of Canada. The Canadian Government was to fund the schools, but it steadily and arbitrarily reduced funding and left it up to the religious organizations to find the minimum required to keep operating. To fill the residential schools, a law was required to force the Indigenous families to send their children to them. Canada obliged by authorizing the Indian agents to take any school age children from their families and put them in the schools. If parents refused, the agents had the power to cut off their annuities and more. Testimony has revealed that parents who opposed sending their children were threatened with prison. The NWMP (now the RCMP) was empowered implement the law. Testimony gathered is eloquent. “children (who) were lured onto boats and planes without parental knowledge, sometimes never to be seen again. Uniformed RCMP pulled children from their mother’s arms; many survivors described the cattle trucks and railroad cars into which they were herded each fall. Night time knocks on the doors and invasions in search of runaway children are reminiscent of war.”The threat of police action was often the means used to return the children to school, “it was the police who brought the runaways back to school, and now it was the threat of police action which stopped a grieving father from trying to find out what had happened to his son” (Funk, 1993: 88). Some accounts refer to how the RCMP assisted by force. “They encircled reserves to stop runaways then moved from door to door taking school children over the protest of parents and children themselves. Children were locked up in nearby police stations or cattle pens until the round up was complete, then taken to school by train” (The Role of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police During the Indian Residential School System, prepared for the TRC, 2011) In short, Canada entrusted the churches with the responsibility to establish residential schools; the government funded them; its Indian agents and its police force were empowered to force parents to send their children to the schools and use a battery of threats. Canada had the power to put an end to the system. But it didn’t, preferring to keep it operating for some 100 years, even though its own civil servants fully informed the government of the criminal nature of the system. The Canadian Government knew Dr. P.H. Bryce was Chief Medical Officer of the Department of the Interior from 1904 until 1921, when he was forced to retire. He was responsible for the health of Indigenous children in the residential schools. He became a “whistle-blower” in 1922 by publishing a booklet titled, “The Story of A National Crime, An Appeal for Justices to the Indians of Canada, The Wards of the Nation: Our Allies in the Revolutionary War: Our Brothers-in-Arms in the Great War (James Hope, 1922, Ottawa). But it was not the first information that became public. In 1907, based on the annual report he submitted to his superiors, The Evening Citizen (now The Ottawa Citizen) ran a front-page article titled, “Schools Aid White Plague — Startling Death Rolls Revealed Among Indians — Absolute Inattention to the Bare Necessities of Health.” Dr. Bryce’s annual reports repeated the same observations and included urgent recommendations for the First Nations. Nothing was done. Slowl he was forced to stop producing the reports. Tuberculosis was rampant in those years. In his reports, Dr. Bryce, who was a specialist in fighting tuberculosis, compared the death rate in cities like Hamilton and Ottawa, Ontario, with those in western reserves. Whereas death rates in the Ontario cities were constantly dropping, in the reserves, and particularly in the residential schools, the death rates were devastating, continually on the rise. The Indigenous population was plummeting each year because of tuberculosis, but each of Dr. Bryce’s reports was snuffed out. Worse yet, representatives of the Indian Affairs Department did everything possible to prevent Bryce from speaking out in public. For instance, he was prevented from speaking to the 1910 Annual Meeting of the National Tuberculosis Association. What about Quebec’s role in this tragedy? Since the children’s bodies were discovered in cemeteries belonging to residential schools, people have been raising Quebec’s role in the tragedy. Some see a link because of the Catholic Church and the religious orders based in Quebec. Others point to Quebec politicians or civil servants who participated in the decision-making by the Canadian government or by British authorities or in the implementation of these policies. Some refer to the two French-speaking battalions from Quebec City sent West in 1885. Inasmuch as individuals, members of political parties or institutions bought into the British order established in Canada in the wake of the first two military conquests and in the British imperial and colonial drive westward, they obviously bear some responsibility. But Quebecers and French-Canadians have often fiercely challenged that order throughout the history of Canada. For instance, in the Declaration of Independence of Lower Canada written in 1838 by the Patriot Robert Nelson, it is stated in the third article: “That under the free government of Lower Canada, all citizens shall have the same rights; the Indians will cease to be subject to any kind of civil disqualification, and will enjoy the same rights as the other citizens of the state of Lower Canada.” The same goes for the Catholic Church, which has been challenged constantly. The British—and Canadian—authorities promoted the Catholic Church, particularly in the wake of Patriot Revolt of 1837-38. Together they hoped to suppress the revolutionary republican ideas inspired by France. As for the two French-speaking battalions under Major-general Middleton’s command sent to put down the resistance in 1885, the British showed their true colours once again. They considered that these French-speaking troops could not be trusted to fight the French-speaking Métis and Riel, so they had them sent far away from combat in Alberta. The Quebec troops quickly learned that they were, and would always be, second class members of the institutions established in British North America (Canada). This story would be repeated over and over again. Making Canada an English country Following the military conquest of the West in 1870 and 1885, which allowed Britain’s Dominion of Canada to impose its sovereignty, it eliminated the French language and culture with almost as much zeal as was deployed to eliminate the Indigenous languages and cultures. In 1890, Manitoba abolished French as an official language and shortly thereafter it prohibited the use of French in schools. (Gabrielle Roy, who was born in Saint-Boniface, Manitoba, recalls in Enchantment and Sorrow how the French-speaking sisters in her Catholic school would teach them in English, but would sometimes sneak out books in French, out of sight of zealous government inspectors.) Saskatchewan and Albert became provinces of Canada in 1905, but the bilingual status that had applied to the North-West Territories was eliminated. A few years later, use of French in government, in courts and in schools was prohibited. Everything old is new again In their fight against the British Empire, Canada’s First Nations and the Métis were not alone; the French-Canadians/Quebecers were not alone either. They were peoples who represented obstacles the European powers, intent on expanding their empires around the world, had to remove. In that sense, they were objective allies of the Chinese, the peoples of India and other Southern Asian countries, the Maoris of New Zeeland, the indigenous peoples of Australia and the United States, and the peoples of Africa. One hundred fifty years later, the same European and North American powers, including Canada, are attempting to restore their hegemony in these same places, though they are meeting vigorous resistance worldwide. The methods used include lecturing these countries on human rights, applying murderous sanctions, and threatening to bomb and intervene militarily in any countries that prefer political and economic independence to the hegemony of great powers. Today, as in the past, these powers have neither the right nor the moral authority to do what they are doing, but that will not stop them. One lesson to be retained from the sorry history of residential schools in Canada is that our solidarity must also mean that we will not allow ourselves to be dragged into imperialist drives against other countries and peoples in the world. Sources Bryce, P.H. The Story of A National Crime, An Appeal for Justices to the Indians of Canada, The Wards of the Nation: Our Allies in the Revolutionary War: Our Brothers-in-Arms in the Great War. James Hope, 1922. Dictionnaire biographique du Canada. Hay, Travis, Blackstock, Cindy, and Kirlew, Michael. Dr. Peter Bryce (1853-1932): whistleblower on residential schools, CMAJ, 2 March, 2020. Kelly, Stéphane. La petite loterie. Comment la Couronne a obtenu la collaboration du Canada français après 1837, Les éditions du Boréal, 1997. LeBeuf, Marcel-Eugène. Au nom de la GRC. Le rôle de la Gendarmerie royales du Canada sous le régime des pensionnats indiens, rapport réalisé dans le cadre de la CVR, 2011 Momudu, Samuel. « The Anglo-Ashanti Wars (1823-1900). Black Past. 24 mars 2018. Morton, Desmond. A Military History of Canada, From Champlain to Kosovo, Fourth Edition. M&S, 1999. Ogg, Arden. An infamous anniversary: 130 years since Canada’s Largest Mass Hanging 27 November 1885. Cree Literacy Network. Reed, Hayter. Memorandum for the Hon(ourable) the Indian Commissioner Relative to the Future Management of the Indians. Stonechild, Blair; Waiser, Bill. Loyal Till Death, Indians and the North-West Rebellion. Fifth House Publishers, 2010 Wolseley, Garnet. “General Lee”. Lee Family Digital Archive. Featured image: Cairn erected in 1975 marking the Battleford Industrial School cemetery (CC BY-SA 4.0) Source URL |