| In the days ahead we must not consider it unpatriotic to raise certain basic questions about our national character. We must begin to ask: Why are there forty million poor people in a nation overflowing with such unbelievable affluence? — Martin Luther King, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? [p. 141] The usage of the term ‘woke’ has spread rapidly in the last ten years from meaning awareness of racial prejudice and discrimination to describing the identity politics of various ethnic groups in the USA. The term has a long history reaching back to the 1930s when Black American folk singer-songwriter Huddie Ledbetter, a.k.a. Lead Belly finished a song advising people with the words to ‘best stay woke, keep their eyes open.’

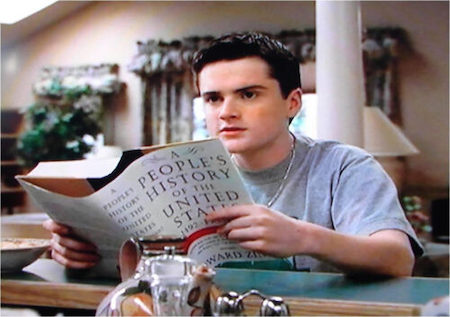

The history of ethnic- or identity- based politics has been a long one in the United States going back to the ethnocultural (ethnic, religious and racial identity) politics of the 19th century. Identity- based politics resurfaced in the 1960s with the Black Panther Party (BPP) (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense), a Black Power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in 1966. In the 1970s, identity politics were seen with the Black feminist socialist group, Combahee River Collective, and spread with the LGBT movements of the 1980s. Today ‘wokism’ is associated with identity-based groups such as Black Lives Matter (BLM). The complexity of identity politics in all its positive and negative forms has become more prevalent in recent years with the production of many ‘woke’ films. These could be described as films that have women in leading positions, gender or racial swaps, and the inclusion of gay characters in a diverse cast, etc. However, prior to this change in ideology there was also the identity politics of dominant heterosexual white men, so for some there is also the satisfaction and feeling of social justice with the depiction of racial and gender reversals. One prominent and popular TV series to look at both sides of the complexity of identity politics was The Sopranos. The episode “Christopher” is the 42nd episode and the third of the show’s fourth season. The teleplay was written by Michael Imperioli, from a story idea by Imperioli and Maria Laurino and was directed by Tim Van Patten. It aired on September 29, 2002. Imperioli, who played Christopher Moltisanti in The Sopranos, is an American actor, writer, and director, and it seems he was also impressed with Howard Zinn’s book A People’s History of the United States which this episode is based on. He even has Tony Soprano’s son reading the book for school over breakfast at home. The episode focuses on Columbus day and the different perceptions of Columbus by individuals of various ethnic backgrounds. The influence of the book on this episode can be seen in the historical and political awareness of the history of identity politics that is depicted. Imperioli not only shows the complexity of various identities in the USA but also how these identities are manipulated to foment strife between different groups both on the street and in the mass media.

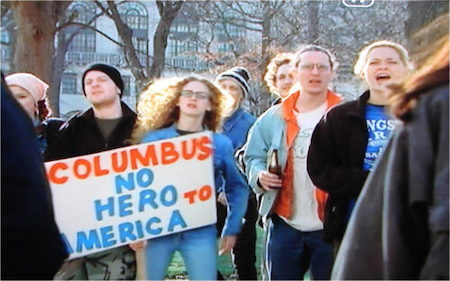

This is very cleverly done in a scene where the Sopranos arrive at an anti-Columbus demonstration being held by Native Americans and students. A bottle is thrown and fighting ensues. It is interesting to see how the different characters are picked out in this scene. The Native Americans look generally like Native Americans (skin color, hair etc), the students (long hair, denim) and the character who threw the bottle is distinguished by combats, black jacket and black beanie (connoting the military, the state, undercover; i.e., agent provocateur). This scene happens so fast it is almost an easter egg (I had to slow it down frame by frame to get a screenshot). Thus, like in real life, the provocateur gets lost in the mayhem and the later clashes seen on the news are described as ‘tragic’.

The complexity of ethnic identity feeds some of the humour in the show, when, for example, Dr. Del Redclay doesn’t realise that Iron Eyes Cody who portrayed Native Americans in many Hollywood films was actually Italian; Pauli didn’t know that James Caan’s heritage is German, not Italian; and Chief Doug Smith, ‘Tribal chairman of the Mohonk Indians and CEO of Mohonk Enterprises’, announces: “Frankly, I passed most of my life as white until I had an awakening and discovered my Mohonk blood. My grandmother on my father’s side, her mother was a quarter Mohonk.” Even Redclay’s TA, Maggie Donner, turns out to be one-eighth Italian – her “great-great something-or-other”.

The same humour is used in the title of Maria Laurino’s memoir, Were You Always an Italian?, which was a national bestseller and explored the issue of ethnic identity among Italian-Americans. Chief Doug Smith represents the use of ethnic identity for private gain. In the 1970s the Supreme Court had ruled that only Indians have the authority to tax and regulate Indian activities by Indians on Indian reservations. Academia does not get off lightly either, as Professor Longo-Murphy, who is invited to give a lunch-time talk on modern Italian-ness to the Italian community, is obviously half Irish. By having Tony’s son read about Columbus and his encounters with the ‘savages’, Tony’s power position as dominant white male is illuminated as he defends Columbus’s actions and thereby shutting down any real discussion of the realities of history while maintaining ethnic group myths (“in this house Christopher Columbus is a hero. End of story.”)

It’s interesting that this episode touched many nerves. In an article on this episode a writer describes the Native Americans as ‘fanatics’ (the author missed the agent provocateur) and describes the dialogue as being “like it was written by an eighth-grader assigned by his history teacher to write up Columbus’s pros and cons.” The whole Columbus theme is described as ‘clunky’, even though in many TV shows the political and cultural life of their characters is generally completely ignored. Out of 86 episodes this was the only one that touched on the cultural and political history of the Soprano family, and still managed to raise a lot of hackles. The reality is that often people don’t know much about their own history and cling to nationalistic biases or myths. For example, a recent survey (2019) discussed in the New York Post noted that: Americans have an abysmal knowledge of the nation’s history and a majority of residents in only one state, Vermont, could pass a citizenship test. The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation surveyed 41,000 Americans in all 50 states and Washington, DC, the organization said Friday. Most disturbingly, the results show that only 27 percent of those under the age of 45 across the country demonstrate a basic knowledge of American history. And only four in 10 Americans passed the exam.The complexity of identity politics was further developed when Furio, an actual Italian gang member from southern Italy, agrees with the negative analysis of Columbus: But I never liked Columbus. In Napoli, a lot of people are not so happy for Columbus because he was from Genoa. The north of Italy always have the money and the power. They punish the south since hundreds of years. Even today, they put up their nose at us like we’re peasants.Italy, the country, the nation, arose out of many different regions, ethnic groups and languages (only a small percentage of Italians spoke Italian at the time of unification in the 19th century). Indeed, the potential for Italy to break up into regions is never too far away either. Gianfranco Miglio, a political scientist wrote in 1990: Lega Nord, a federalist and, at times, separatist political party in Italy, proposed “Padania” as a possible name for an independent state in Northern Italy. According to Miglio, Padania (consisting of five regions: Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria and Emilia-Romagna) would become one of the three hypothetical macroregions of a future Italy, along with Etruria (Central Italy) and Mediterranea (Southern Italy), while the autonomous regions (Aosta Valley, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Sicily and Sardinia) would be left with their current autonomy.Thus, the definition of ethnic or even national identity can be rewritten at any time. The lines of the map of Europe were constantly being drawn and redrawn depending on the political and military strength of local elites who bring their ‘people’ with them and redefine their identity when and how it suits them. As elites gain strength they demand more autonomy, in defeat they are integrated into a larger region; e.g., Catalonia. The only way people can stop being a bobbing cork on the sea of international geopolitics is to switch from the vertical structure of ethnicity (full class structure) to a horizontal structure of class (e.g. trade unions). The particularist policies of identity politics leaves groups open to manipulation and divide and rule. The American journalist Christopher Lynn Hedges has written that identity politics: “will never halt the rising social inequality, unchecked militarism, evisceration of civil liberties and omnipotence of the organs of security and surveillance.”

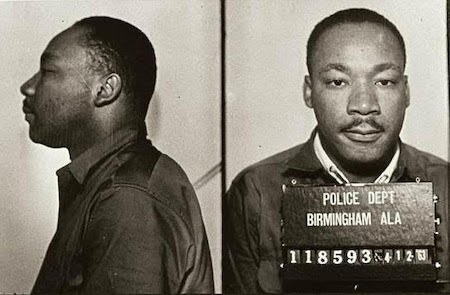

King was arrested in 1963 for protesting the treatment of blacks in Birmingham. It seems that Martin Luther King came to the same conclusions about the weakness of identity politics when he wrote in Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?: Too many Negroes are jealous of other Negroes’ successes and progress. Too many Negro organizations are warring against each other with a claim to absolute truth. The Pharaohs had a favorite and effective strategy to keep their slaves in bondage: keep them fighting among themselves. The divide-and-conquer technique has been a potent weapon in the arsenal of oppression. But when slaves unite, the Red Seas of history open and the Egypts of slavery crumble. [p. 132]In 1968, King was involved in organising the Poor People’s Campaign to bring economic justice to all those struggling to make ends meet. It was a “multiracial effort—including African Americans, white Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Indigenous people—aimed at alleviating poverty regardless of race.” The Poor People’s Campaign “sought to address poverty through income and housing. The campaign would help the poor by dramatizing their needs, uniting all races under the commonality of hardship and presenting a plan to start to a solution. Under the “economic bill of rights,” the Poor People’s Campaign asked for the federal government to prioritize helping the poor with a $30 billion anti-poverty package that included, among other demands, a commitment to full employment, a guaranteed annual income measure and more low-income housing. The Poor People’s Campaign was part of the second phase of the civil rights movement.”

The necessity for unity between black and white is made more explicit by King in his book, where he writes: This proposal is not a “civil rights” program, in the sense that that term is currently used. The program would benefit all the poor, including the two-thirds of them who are white. I hope that both Negro and white will act in coalition to effect this change, because their combined strength will be necessary to overcome the fierce opposition we must realistically anticipate. [p. 174]King was not naive about the potential conservative backlash such unity would create but saw it as the only way forward, as the movement would encompass ever greater numbers of people. As we have seen the fluid nature of identity politics can be summed up with the observations that: maps change (independent city-states and regional republics, ‘Padania’), identities can be complex (North vs South, intermarriage), identities are not fixed (Cody, Caan), and identities can be manipulated (Divide and Rule, ethnic ‘leaders’). King came to the realisation that any campaign group will be limited by the size of the movement and the breadth of its ideology, and soon moved away from his own prejudices and biases, although he was not able to bring his dream to fruition. Source URL |