How the U.S. transformed a tiny African state into a hub of imperial aggression

In a blatant threat to China’s presence, Djibouti recently hosted the US-led “Allied Appreciation Day,” in which Britain, France, and Japan showcased “a variety of equipment that is part of their military operations in the Horn of Africa” (HOA). The Pentagon’s Combined Joint Task Force-HOA reported that the events fused Armistice, Remembrance, and Veterans’ Days. Attendees participated in “demonstrations featuring a variety of allied military capabilities to include a military flyover.” Successive Djiboutian regimes have clung to power by promoting their small country in the Horn of Africa as a vital tool in the West’s quest for global dominance. During Europe’s late-19th century Scramble for Africa, the French colonists understood the strategic importance of the region for trade ships and naval deployments. After the Second World War and particularly after the September 11, 2001 attacks on the US, the Pentagon seized France’s imperial mantle and expanded a major military base, Camp Lemonnier (which, for many years, the US misspelled by leaving out an “n”). Today, American military and political planners fear the presence of China in what they consider to be “their” African territory. In 2017, China opened its first, and at the time of writing, only confirmed foreign military base — the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Support Base — 30 minutes northwest of Camp Lemonnier. As the right-wing NY Post cited dubious warnings by unnamed US officials about China’s construction of a secret base in Equatorial Guinea (EG) on the other side of Africa, the US Africa Command has quietly expanded its operations in Djibouti. A former colonial power maintains its grip on Djibouti Djibouti has a population of around 1 million. With 48 deaths per 1,000 live births, its infant mortality rate remains one of the worst in the world, while life expectancy hovers around 67. Over 400,000 Djiboutians live in extreme poverty, with 90 percent of the nation’s food dependent on imports. Around 60 percent of the population is ethnic Issa (sometimes broadly referred to as “Somali”) and 35 percent Afar (a.k.a., Danakil). Between 600 and 1000 migrants and asylum seekers pass through Djibouti daily, nearly half of whom are children. The US Department of Labor (DoL) says: “Children in Djibouti are subjected to the worst forms of child labor.” In addition to begging and selling drugs, “[s]treet work, such as shining shoes, washing and guarding cars, cleaning storefronts, sorting merchandise, collecting garbage, begging, and selling items” is common. In addition to human trafficking, Djiboutian children are at risk of rape and other forms of sexual abuse. The country hosts “the largest number of foreign military installations in the world, including thousands of military personnel and security contractors.” The DoL concludes: “This foreign military presence heightens the risks of commercial sexual exploitation of girls.” Western colonial rule in what is now Djibouti began in the mid-1800s. France purchased land on which it established stations for the steamships that passed through Egypt’s Suez Canal, north of the territory. In the decades that followed the Second World War, the broader region was known as French Somaliland. A likely-rigged vote in 1958 saw the population choose to remain under French control. In response to several factors including domestic independence movements, Somali claims to the territory, and continued Ethiopian usage of the ports, the French established the Territory of the Afars and the Issas in 1967. A decade later, and following negotiations with the colonial power, Hassan Gouled Aptidon of African People’s League for Independence, became President, forming the People’s Rally for Progress. Gouled governed the one-party state until his alleged nephew, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, replaced him in 1999. With France’s Indian Ocean navy squadron based there, the Franco-Djiboutian Defense Treaty 1977 granted the “former” colonial power unimpeded access to air and maritime facilities. Enter America: “Use Djibouti,” maintain a “pro-Western course” Basing his assessment on a commissioned CIA report in 1979, Paul B. Henze of the National Security Council Staff advised President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, that the French military presence in Djibouti would be enough to prevent the Soviet-backed Ethiopian government from invading. “[I]f we are going to continue to use Djibouti (and there are good reasons for doing this), we need to be frank with the French about our need for their alertness and support there.” President Gouled saw foreign de facto occupation as a bulwark against potential aggression by Djibouti’s neighbors, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. A heavily-redacted CIA Intelligence Estimate from 1986 describes the country as basically a city-state. “Largely because of its excellent deepwater port and chokepoint location on the Bab el Mandeb Strait (sic),” which separates the Gulf of Aden from the Red Sea, “Djibouti has long been subject to competing African, Arab, Soviet, and Western interests.” Indicative of Cold War paranoia, the Soviet “interests” highlighted at the outset of the report are later revealed to be scholarship programs and a maritime visit. The CIA lauded Gouled’s “pro-Western course,” rejecting, for instance, aid packages offered by Libya’s then-ruler, Muammar Gaddafi. “[I]n a region dominated by Marxist and military regimes, the Gouled regime enjoys French security protection and supports Western interests,” particularly by providing the US with a port, airfield, and reconnaissance airspace. When Ethiopia’s ruler was deposed in 1991, Eritrea gained independence. Robbed of its port, Ethiopia turned to Djibouti, but Afar rebels known as the Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy (FRUD) based themselves in Ethiopia. The Dini faction of FRUD later claimed that Ethiopia was supporting Djibouti’s Issa-majority government. A Civil War ensued leading to a peace agreement in 1994, when a small number of Afar were given token positions in Gouled’s government. Post-9/11: “The primary base for US operations” Significant elite US interests in Djibouti began after 9/11, when the Navy and the Central Command (CENTCOM) effectively took over the old French Foreign Legion fort, Camp Lemonnier, and established a permanent presence. In 2002 under President George W. Bush, the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) began surveillance and reconnaissance of alleged “al-Qaeda” operatives in neighboring Somalia from Lemonnier. By the end of that year, at least 800 US Special Operations Forces were present. The period also saw the launch of exercises by the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit. In November 2002, six Yemeni “al-Qaeda” suspects were killed by a CIA Predator operator whose drone was launched from Djibouti. In a rare moment of honesty, the New York Times article exposing the attack added: “The sea lanes near Djibouti are particularly crucial since they are used for commercial shipping and to transport American war matériel to the Persian Gulf.” In May 2003, CJTF-HOA personnel had arrived. Lemonnier is described by the US Center for Naval Analysis (CNA) as “the largest U.S. military installation in Africa.” The CNA highlights Djibouti’s importance to rival powers: its regional “stability,” “strategically important position next to the Bab el Mandeb (sic), a critical maritime chokepoint[,]” while serving “as the main port for landlocked Ethiopia.” The oddly-named “Commander, Navy Installations Command” describes Lemonnier as “the primary base of operations for U.S. Africa Command in the Horn of Africa.” Between 2004 and 2011, Presidents Bush and Barack Obama respectively sold Djibouti a total of $68 million-worth of arms and services under a single program. In late-2006, the US and Britain used Ethiopia as a proxy to invade Somalia and replace the moderate Islamic Courts Union government with an extremist entity called the Transitional Federal Government. Djibouti later posed as a peace-broker between the warring Somali and Ethiopian factions, but behind the scenes the Franco-American-backed Djiboutian Armed Forces were training hundreds of Somali military officers. Besides using Djibouti as a base for the CIA, Special Forces, the Navy, and other operations, the US trains domestic enforcement units in the country. In 2007, as domestic tensions simmered with the Afar people and potential conflicts brewed with neighbors, the Marines were pictured instructing the Djibouti National Police “on basic weapons procedures and room clearing.

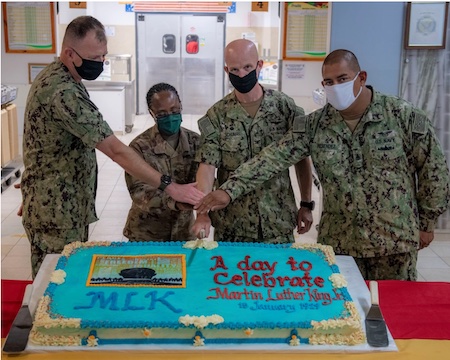

US psy-ops in the Horn of Africa: celebrating MLK on a military base and “the gift of hope” In 2008, the newly-created US military alliance known as AFRICOM took over operations in Djibouti from CENTCOM. That June, the French and British joined with the militaries of 10 African nations to cooperate on maritime operations. At the time, countering Somali “piracy” was a widely-used pretext for regional dominance. As the transfer to AFRICOM was arranged, CJTF-HOA continued its propaganda offensive against Djiboutians by painting US military personnel in a positive light. Staff “donated more than 50 book bags containing school supplies, flip flops, shampoo, soap and treats to girls at Center Aicha Bogoreh [sic],” in Djibouti City. As he rang in Christmas in 2008 with the lighting of trees and singing of festive songs, Rear Admiral Philip Greene said of the Navy: “We are sharing our time and talents with the people of Eastern Africa, giving them the gift of hope for a better, more secure future.” The “gift of hope” is part of US psychological operations, soft power, or political warfare as the tactic is interchangeably called. In January 2009, in a prime example of the soft power tactic, CJTF-HOA personnel “celebrated” Martin Luther King Day with a program entitled, “Realizing the Vision,” in which AFRICOM highlighted King’s life through speeches, a slideshow, and a performance of the somber Sam Cooke ballad, “A Change is Gonna Come.” A “Hollywood Handshake Tour” later that year took the “gift of hope” to new heights with visits by industry b-listers Christian Slater, Zac Levi, Joel Moore, and Kal Penn, who each “personally thank[ed] members for their sacrifice.” In July, the Navy Seabees and CJTF-HOA built a canteen for the newly-constructed Douda de Ecole Primary School. A year later, the US hosted a meeting by the Djiboutian Chamber of Commerce in an effort to present the de facto US occupation as an investment opportunity for the business class.

As the PR-friendly pleasantries continued, so too did the military training. In September, officers of the Ugandan Senior Command and Staff College visited Djibouti to study with the CJTF-HOA. Facilitated by the Lemonnier-based 449th Air Expeditionary Group (or Flying Horsemen), Ethiopian Air Force officers convened with Djiboutian forces to discuss operations including airdrops. Remote warfare: overcoming “the tyranny of distance” In addition to acting as a hub for the training of Ethiopian, Somali, Ugandan, and other forces, Djibouti hosts regional propaganda broadcasters and privatization outfits that operate as aid agencies. A 2010 US Embassy cable notes that Djibouti is home to “[US government] broadcasting facilities used by [the] Arabic-language Radio Sawa and the Voice of America Somali Service, the only USAID Food for Peace warehouse for pre-positioned emergency food relief outside [the continental U.S.], and naval refueling facilities for U.S. and coalition ships.” That same year, Lemonnier hosted Africa’s first Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Summit Conference. Basing forces near strategic locations and using digital relays to aid drone strikes defeats what the Pentagon calls “the tyranny of distance.” Seated in joint operations rooms, at least three British officers in the Camp assisted CJTF-HOA-led drone operations against targets in Yemen. By the mid-2010s, drone killings had been committed from Djibouti against people in Afghanistan, Mali, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen. In 2012, BT (formerly British Telecom) built a $23m fiber-optic cable for the US Defense Information Systems Network and National Security Agency. The cable ran from the US Air Force-run Royal Air Force Croughton (north of London) to Naples (Italy) and onto Camp Lemonnier. The broadband service was 30 times faster than commercial capacity and could carry live drone video. Describing Lemonnier and by extension Djibouti as “a sun-baked Third World outpost,” the Washington Post reported that the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) was instrumental in setting up Lemonnier and its crucial drone component, with at least 300 JSOC personnel working secretly at the base. Enter China: threats are “exaggerated” The Trump-era Secretary of State’s Policy Planning Staff kept a close eye on China’s presence in Djibouti. It wrote: “In 2017, China established in Djibouti its first foreign military base. The base looks out on the Bab-el-Mandeb Straits in the Gulf of Aden, through which passes nearly 10 percent of the world’s total seaborne-traded petroleum.” The report highlighted the perceived threat to US energy market dominance. “This comprises 6.2 billion barrels per day of crude oil, condensate, and refined petroleum. Together with China’s anti-piracy activities in the Gulf of Aden and growing presence in the Gulf of Guinea,” it concluded, “the base has extended China’s military reach off Africa’s coasts and into the Indian Ocean.” China and Djibouti established diplomatic relations in 1979 but did not expand militarily until 2009, with China’s counter-piracy operations in the nearby Gulf of Aden. In 2015, China announced plans to join seven other countries, including the US, to establish its first and only foreign base in Djibouti. Under the subheading “Don’t Believe the Headlines,” the US Center for Naval Analysis wrote: “media reporting on Chinese economic ties is sometimes exaggerated.” It does not list threats to US “interests” or allies in the context of China’s military expansion, but rather China’s intentions to launch counter-piracy, intelligence collection, evacuation missions, counterterrorism, and peacekeeping operations (i.e., China’s contribution to UN forces). In July 2015, the Pentagon reported that the 1st Marine Regiment, the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), the Navy Battalion Landing Team 3rd Battalion, and the USS Anchorage exercised on Arta Beach, Djibouti. Executing attack and maneuver drills with machine guns, squads, and night attacks, the 15th MEU went ashore “for sustainment training to maintain and enhance [their] skills.” Between September and October 2015, the 15th MEU participated in a bilateral training exercise with the French 5th Overseas Combined Arms Regiment. The 15th MEU’s reconnaissance element trains Rapid Response Teams to send ashore in Djibouti, Hawaii, Iraq, and Singapore and to “push secure voice, video, and data back to the ship with a very small foot print.” Maj. Matthew Bowman of the Communications Department, said: “we have … to be able to project power ashore quickly.” What US forces do with the training Much of the US-led allied training traces back to Djibouti. So-called violent extremist organizations are entities that operate outside domestic law and make local environments unsafe for US operations and unstable for US investors. For these reasons, the Pentagon seeks to counter VEOs. Through military information support operations (MISOs), the Lemonnier-based CJTF-HOA oversees the Ohio-based 346th Tactical Psychological Operations Company (Airborne). Under the rubric of the African Union Mission in Somalia to counter al-Shabaab, the MISO operations involve training the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF). Because locals tend to broadly support extremist groups as leverage against US imperialism, PSYOPs try to propagandize locals into backing the US. Another example is the Sicily-based Special Purpose Marine Air Ground Task Force 12 (SPMAGTF-12), which worked with the California-based 4th Force Reconnaissance Company to train the UPDF to counter the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a cohort of bandits which seeks to overthrow the US-backed government of Uganda. The continued existence of the LRA gives the US military an excuse to maintain a troop presence, or at least proxy presence, in Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan, where LRA leader Joseph Kony is supposedly hiding. He is a “Christian” version of the omnipresent Osama bin Laden, who for many years offered the US a pretext to invade multiple nations from the Middle East to Central Asia. The SPMAGTF-12 relies on support from Marines in Lemonnier. Much of the US activity in Djibouti is either covert and therefore not reported or confined to press releases by the Pentagon. Recently, however, CNN painted the Pentagon as the Lone Ranger riding to the rescue in its coverage of the presence of the US Army 1st Battalion 75th Ranger Regiment in Djibouti, which was ready to deploy for supposed evacuations in Ethiopia. Beyond the growing deployment of ground and special forces in the Horn of Africa, the US Navy is making waves. In August 2021, Comorian and Somali personnel worked with US service members as part of Cutlass Express at L’Escale Marine, Djibouti, to practice “visit, board, search and seizure” procedures and simulate various scenarios, including counter-piracy. A de facto occupation The US presence in Djibouti is a de facto occupation which ensures American naval dominance of the region, as well as continuing training of regional forces and growing surveillance operations. European militaries are also benefiting from shared, US-led exercises in the region. The build-up exacerbates a power struggle between what the US hopes is a unified West against what they are trying to turn into an increasingly isolated China. In recent years, the US has sought to weaponize Japan by pushing successive governments to drop the Peace Clause of their constitution and turn up the heat on China. In September, the Japanese Ambassador to Djibouti, Umio Otsuka, met with the US Army Commander at Lemonnier, Maj. Gen. William Zana, “to dAir Forceiscuss future plans for combined cooperation.” Under CJTF-HOA, the so-called Japanese Self-Defense Forces trained in target practice at the Djiboutian Police Range. In November, a US Air Force B-1B Lancer from the 9th Expeditionary Bomb Squadron and a C-130 Hercules, two F-35 Lightning IIs from the UK Carrier Strike Group’s HMS Queen Elizabeth, two French Dassault Mirage 2000s, and a Japanese P-3 Orion flew missions over Djibouti. In December, it was reported that, as part of Exercise Bull Shark, Spanish forces had trained with the 82nd Expeditionary Rescue Squadron in the Gulf of Aden, “to strengthen personnel recovery capabilities in support of the Warfighter Recovery Network initiative throughout Africa.” As the Pentagon takes the brute-force approach to countering China’s Africa presence, the US increasingly relies on old proxy outfits like NATO while developing new ones, like allied forces in the Horn of Africa. Given that all three major powers have nuclear weapons, Western concerns over pandemics and climate change could prove ephemeral in the face of a miscalculation or worse, a deliberate military action. Source URL |