A French death warrant against Dag Hammarskjold comes to light

Six decades after the unexplained death of United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold and 15 other people in a plane crash in Central Africa, a new discovery in French government archives may bring researchers closer to the truth and answer a famous Cold War riddle: Who killed Hammarskjold? The discovery of an important clue happened in November 2021, following years-long research into the death of the secretary-general. It began with a yellow folder, whose cover was marked with an “H” in blue and the words “TRÈS SECRET” written across the top in a red stamp. “H” stood for Dag Hammarskjold, it turned out. The file from the French intelligence service (SDECE), dated July 1961 and destined for French Prime Minister Michel Debré, was kept in the French National Archives. It contained a typewritten death warrant against U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold, issued by a mysterious “executive committee” that had “gathered to examine . . . the behaviour of Mister Hammarskjoeld in Tunisia,” where French forces were besieged by Tunisian militias in the coastal town of Bizerte and the secretary-general tried to intervene on July 26, 1961.

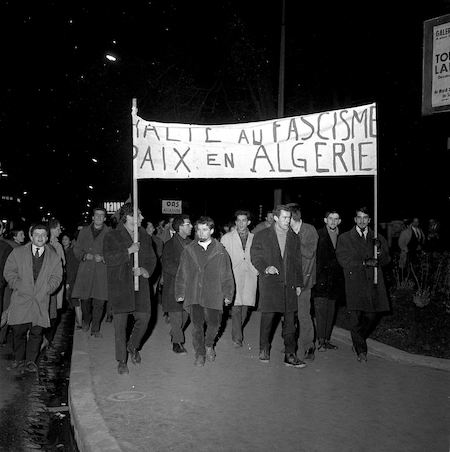

Asserting that Hammarskjold’s “angst of the Russians” made him “change his mind and decide to support them in the Congo,” another serious crisis facing the U.N. at the time, the warrant concluded that it was “high time to put an end to his harmful intrusion [sic]” and ordered “this sentence common to justice and fairness to be carried out, as soon as possible.” The “angst of the Russians” openly referred in the letter to the U.N. presence in Congo and the oversize influence of Afro-Asian countries in the peacekeeping mission there. The warrant had no signature. Just three letters and a notorious acronym: OAS (Organisation Armée Secrète, or Secret Armed Organization), a far-right French dissident paramilitary group opposing Algerian independence and the Gaullist regime. The clandestine movement, which was mostly operational from 1961 to 1962, even tried to murder President Charles de Gaulle on Aug. 22, 1962. It killed 1,700 to 2,200 people, mostly French and Algerian civilians, French soldiers, police officers, politicians and civil servants, during its brief existence.

Somehow, the death warrant — a facsimile that seemed to be a transcription of an original letter — ended up in the personal files of a legendary man from the shadows and chief adviser to President de Gaulle on African affairs and mastermind of the “Françafrique” networks, Jacques Foccart (who lived from 1913 to 1997). The document appears to be authentic, given that it was found in Foccart’s confidential files preserved by the French National Archives. The text itself mentions the Bizerte crisis and Hammarskjold’s intervention in Tunisia, which puts the letter sometime between July 26 and 31, 1961, as the date cannot be fully read on the envelope. A 2019 investigation by the French government into the cause of Hammarskjold’s death makes no reference to link the OAS to the 1961 crash of the Albertina plane carrying the secretary-general and others. Was the original letter intercepted before it reached New York City and Hammarskjold himself? It is impossible to know. Did the U.N. ever see it? Probably not, considering there are no traces of it in the U.N. archives or in Brian Urquhart’s personal notes on Hammarskjold, who was originally a Swedish diplomat. As a former U.N. under secretary-general for special political affairs, Urquhart, who was British, wrote a biography of his boss. Six weeks after the approximate date on the letter, Hammarskjold was dead. On Sept. 18, 1961, he was killed along with his party of 15 other U.N. officials and air crew in a plane crash that night near Ndola, in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), while trying to stop hostilities in Katanga, a breakaway province in the newly independent Congo.

U.N. Investigation Reopened in 2016 Their deaths were ruled an accident by a North Rhodesian official investigation, while a subsequent U.N. investigation refrained from reaching such a conclusion, given the many outstanding questions regarding the crash. The U.N. investigation was reopened in 2016 by then-Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, following newly uncovered testimonies of African eyewitnesses and renewed suspicions that there had been another plane in the air that night. After six years and two interim reports, Mohamed Chande Othman, a former Tanzanian chief justice who has been leading the independent inquiry for the U.N. on Hammarskjold’s death, is expected to hand his conclusions to U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres in September 2022.

Since 2016, Othman had tirelessly been asking member states to “conduct a thorough review of their records and archives, particularly from their intelligence agencies,” as part of the inquiry’s mandate. Despite having gathered a “significant amount of evidence,” Othman, known as a U.N. “eminent person,” is at pains to “conclusively establish” the exact circumstances of the crash, Othman’s latest report says. Several major countries have been openly reluctant to cooperate, in particular the United States, Britain, South Africa and, to a lesser extent, France. Indeed, in 2018, the French government finally named a historian, Maurice Vaïsse, to respond to Othman’s request. The result was disappointing. The report of Vaïsse, confidentially released in 2019, established that after an exhaustive search marred by bureaucratic and regulatory hurdles, there was no groundbreaking document to be found by the French regarding Hammarskjold’s death. As to why the OAS, the far-right French paramilitary group, would have threatened the secretary-general may be manifold: the Swedish diplomat was loathed within French military circles for his intervention in the Suez crisis in 1956, when he tried to broker a cease-fire; for his repeated attempts to take the issue of the Algerian war to the Security Council; and for his controversial intervention in Bizerte, where he again tried to broker a cease-fire, this time unsuccessfully. The OAS, however, never claimed responsibility for Hammarskjold’s death. In Paris, the group was known as “OAS Metro” and was led by a fugitive Foreign Legion captain, Pierre Sergent,under the distant command of Gen. Raoul Salan, who was hiding in Algeria. “If this is the work of OAS Metro, this could only have been done by Pierre Sergent himself, since it was a very military organization, in a hierarchic sense,” claims French historian Rémi Kauffer. “No subordinate would have dared author such a letter.” Other experts, such as Olivier Dard, a French historian at Paris La Sorbonne University, and an expert on the history of the OAS, nevertheless “doubt” it could have been penned by Sergent, a prolific writer who became a right-wing politician and died in 1992. While use of harsh language was an OAS trademark, the style of writing in the letter, improper and trivial, tends to exonerate Sergent, who remained at large until an amnesty law was approved in 1968.

Question Remains If the death warrant reached would-be assassins in Katanga, another question remains: Who could have carried out the killing? Until now, no OAS presence in Katanga has ever been established. Yet a trove of previously disconnected documents found in declassified French, Belgian, British and Swedish national archives that I thoroughly examined while researching Hammarskjold’s death gives credence to a potential OAS plot against the secretary-general. Surely, there were OAS sympathizers among the two dozen French officers who had been sent to fight under the Katangese flag, including Yves de La Bourdonnaye, a paratrooper and expert on psychological warfare, and Léon Egé, a seasoned clandestine radio operator who would later be identified as the man who threatened a Norwegian officer with a knife on July 14, 1961, according to an archived U.N. document. The Norwegian officer, Lt.Col. Bjorn Egge, turned out to head the U.N. Military Information Branch in Katanga and was in charge of tracking and expelling all foreign mercenaries hired by the separatist regime. Egé described Katanga as “the last bastion of white influence in Africa,” contending that “every white man in the U.N. is a traitor to his race.” On Sept. 20, 1961, Egé wrote to a Katangese official, in a letter found in Belgian archives: “H is dead. Peace upon his soul and good riddance. He bears a heavy responsibility in this bitter and sad adventure.” In 1967, Egé was named by Le Monde as an OAS recruiter in Portugal. A third man, Edgard Tupët-Thomé, a former Special Air Service (or SAS, a British special forces unit) and French commando, also had a brief stint in Katanga. He is mentioned by French historian Georges Fleury in a book about OAS as being a member of OAS Metro. Before leaving Katanga, Tupët-Thomé, a demolition specialist, had been heard boasting, according to the U.N. representative in Katanga at the time, Conor Cruise O’Brien: “The U.N.? No problem. 20 kilos of plastic and I will take care of it!” Plastic, a soft and hand-moldable solid form of explosive material, was the weapon of choice among OAS operatives. On Aug. 30, 1961, O’Brien, who was also a former Irish diplomat and politician as well as a writer, warned his superiors in Léopoldville (now called Kinshasa) and New York City that his deputy, Michel Tombelaine, had been threatened by members of OAS: “The following message arrived in an envelope with the Elisabethville postmark. ’28 August 1961 — Tombelaine UNO Elisabethville. 48 hours ultimatum departure from Katanga or else. O.A.S. / Katanga,’” according to U.N. archives. On Sept. 6, the U.N. discovered that a guerrilla warfare group led by a French mercenary officer, Maj. Roger Faulques, who used to be Sergent’s direct superior in the Foreign Legion, was planning to “use plastic bombs against U.N. buildings” and had set up a “liquidation” list against U.N. civilian and military leaders, according to another U.N. archived document.

When the Albertina carrying Hammarskjold and the 15 others crashed on Sept.18, a South African witness in the area, Wren Mast-Ingle, walked to the site and stumbled upon a group of white mercenaries wearing combat fatigues, before they ordered him to leave at gunpoint. When shown different types of camouflage outfits much later, Mast-Ingle pointed at a leopard-like scheme and “funny caps, with a flap,” he recalled, identical to the type of cap worn by French paratroopers in Algeria. Another witness, a Belgian named Victor Rosez, would later identify the same kind of fatigues discarded by a group of mercenaries wearing civilian clothes in Ndola, near the crash site. In the decades since the crash, a string of testimonies has also mentioned a small outfit of French mercenaries spotted near Ndola around the time of the tragedy. The testimonies seem to originate from a U.N. Swedish officer in Katanga, Col. Jonas Waern, who shared his views with Hammarskjold’s nephew, Knut Hammarskjold, who would later become director-general of IATA (International Air Transport Association) and died in 2012. On April 5, 1962, a former U.N. director of public information and close confidant of Hammarskjold, George Ivan Smith, wrote to Conor Cruise O’Brien, in a letter found at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University: “I am more and more convinced of a direct OAS link.” In December 1962, The Scotsman newspaper reported that “O’Brien still thinks it possible that Hammarskjöld and his party were murdered by French OAS men.” “I now understand that during all this time a psychological warfare commando, led by famous French ‘Colonel’ Faulques [sic], was stationed in Ndola,” Knut Hammarskjold wrote to Smith on Feb. 5, 1963. Could such a group have carried out the death warrant apparently issued by the OAS? To answer this question, the U.N. investigation led by Othman — who is likely to conclude his work by September — must first and foremost clarify these points:

Maurin Picard is a French journalist and the author of a book on Dag Hammarskjold, Ils ont tué Monsieur H? (Who Killed ‘Monsieur H?), Seuil, 2019. Source URL |