|

“[This death] … is a hard blow, it is a tremendous

blow to the revolutionary movement because, without any doubt, it deprives it

of its most experienced and capable chief. But they who sing victory are

mistaken. They are mistaken who believe that his death is the defeat of his

ideas …”

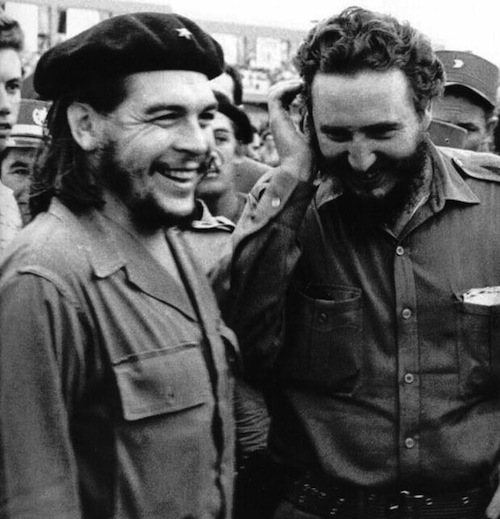

Eulogy for Che Guevara

Fidel Castro Ruz, October 1967

Castro’s

words on the death of his friend and comrade can just as easily apply to Fidel

himself.

When

you visited Cuba, you knew you were in the presence of something great. Here

was a smallish nation, in the shadow of and a direct line of fire from, the

world’s superpower, proudly doing its own thing. Partly by choice, partly through

necessity.

For

all its shortcomings – and there are many – this is a country that built

itself, on its own terms, and with its own vision of what decency and caring

for humanity really means.

In

1956, no one could have dreamed that Cuba would become what it is today.

In

1959, no one foresaw the heavy weights that would be placed on the shoulders of

Cubans who believed their country belonged to them, and that it was not simply

a casino and brothel for the wealthy class of the United States. They didn’t

anticipate the churlishness of Dwight Eisenhower and his vice-presidential hand

puppet, Richard Nixon.

In

1961, an excursion straight out of a Monty Python skit made the United States

look like a group of inept fools. No one might have guessed the petulant

blockade that would follow would still be in place more than fifty years later.

In

1962, the world teetered as two men of immense personal strength and ego tested wills

in a game of chicken over this small island. The bombs were dismantled, and the

moment passed; but the world knew that someone had blinked. It is generally wrong about who that was.

In

1967, one of the romantic heroes behind the freeing of this country from

capitalist clutches was killed trying to bring about similar changes elsewhere.

And although there are those who see Che Guevara today as nothing more than the

patron saint of t-shirts, people with a sense of history and a genuine desire

for the betterment of mankind still honour the man eulogized by his dear friends.

In

1989, with the demise of the Soviet Union imminent, no one gave Cuba a chance of

surviving. But it reinvented ways of delivering to its people those

necessities of life that they have come to believe are birthrights.

In

2016, accolades and criticisms have begun to pour in for the man who was there

through all of this, and without whom this world would be a much poorer place.

|

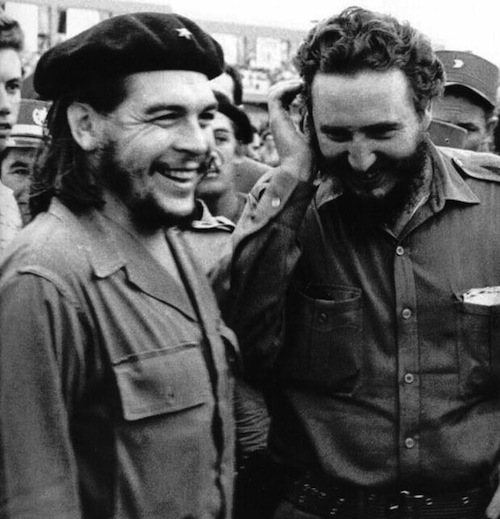

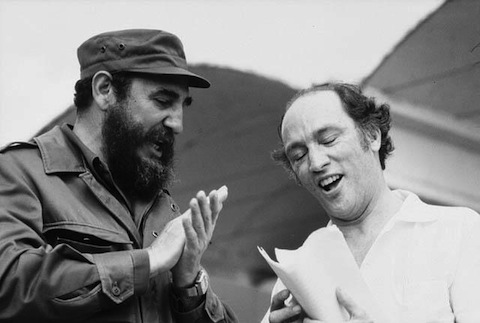

| Fidel & Che in happier times

|

Background

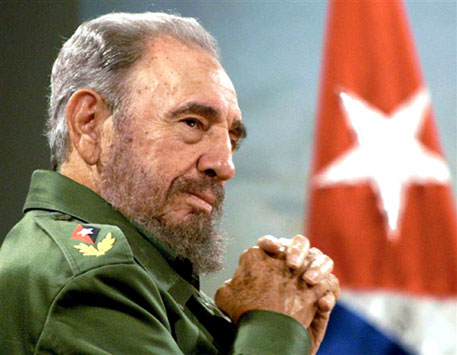

Fidel

Castro Ruz (1926-2016) was a giant of his time. Reviled by much of the world,

and even by some of his fellow countrymen, a sober analysis of his impact can’t

fail to see that Cuba, and Latin America, are better for having known him.

He

was born Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz, near Birán in Oriente province Cuba, the

third of six children: two brothers, Raul and Ramon, and four sisters,

Antelita, Juanita, Emma, and Augustina. His father, Angel, was a wealthy sugar

plantation owner, born in Spain; his mother, Lina Ruz Gonzalez, had been a maid

to Angel's first wife at the time of Fidel's birth. By the time Fidel was 15, the

first marriage was over and Angel wedded Fidel's mother. His father formally

recognized Fidel at the age of 17, and his name was changed from Ruz to Castro.

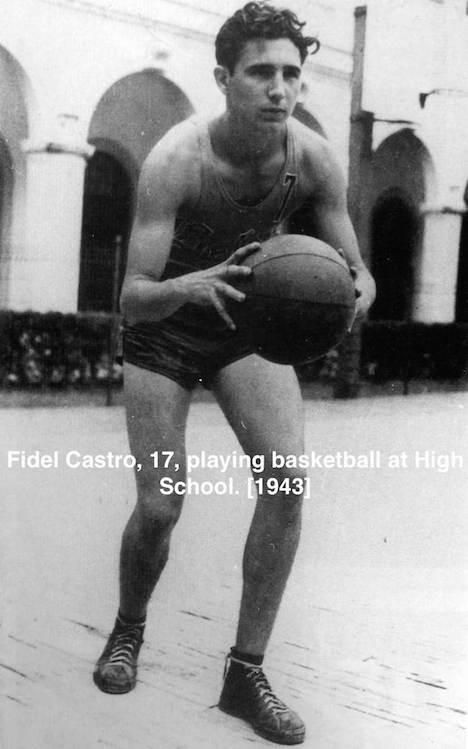

Fidel was educated in private Jesuit boarding schools,

growing up with a life of privilege among the poor of Cuba. Although he was

apparently gifted academically, he was initially interested only in sports –

particularly baseball. Still, in 1945, he entered law school at the University

of Havana and soon immersed himself in the heady climate of Cuban nationalism,

socialism, and anti-imperialism. For a Cuban, by default, anti-imperialist

meant anti-American.

|

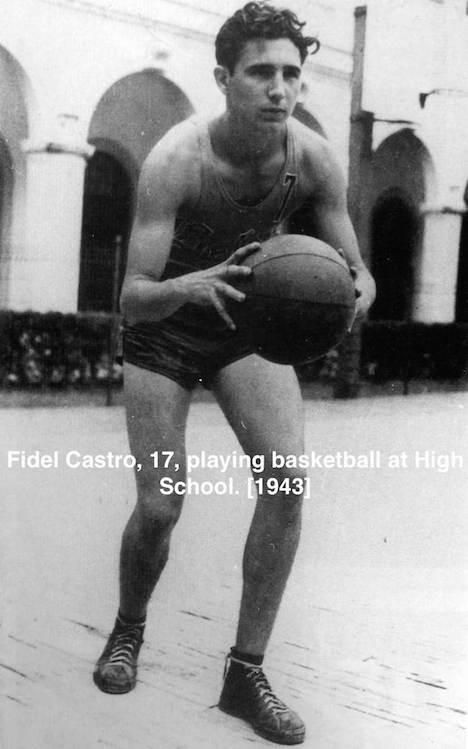

| Fidel in high school, 1943 |

In 1947, having become passionately interested in

social justice, he travelled to the Dominican Republic to join an expedition

attempting to aid in the overthrow of the dictator Rafael Trujillo. Although

the coup fizzled almost as soon as it started, Fidel’s enthusiasm for reform

was only strengthened.

In one of the odd twists of fate, Castro returned to

the University and joined the Partido Ortodoxo, an anti-communist party. It had

been founded for the purpose of reforming corruption in Cuban politics.

By 1948, Fidel was married to Mirta Diaz Balart,

daughter of a wealthy Cuban family. Along with their child, Fidelito, the

Castros were exposed to a wealthy lifestyle and political connections. He stood

for election to the Cuban parliament, but a coup led by General Fulgencio Batista

overthrew the government and cancelled the upcoming elections. Fidel soon found

himself without a political platform, and with little money to support his

family (the marriage finally came to an end in 1955).

|

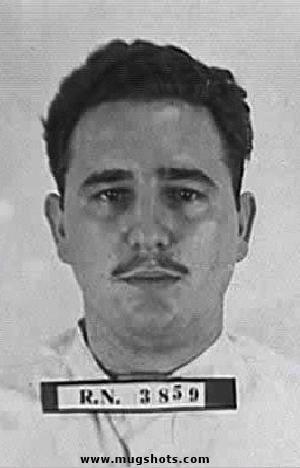

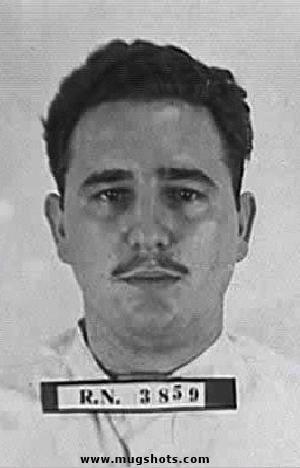

| Imprisoned and released by Batista

|

But in 1953, Fidel, along with a group of about 150 Ortodoxo

members – who had fully expected to win the 1952 general elections – joined

together in an attempt to overthrow Batista with an attack on the Moncada

military barracks. Like the half-baked Bay of Pigs exercise that was still years

in the future, this attack was a failure before it started. Castro was

captured, and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

In one of history’s biggest mistakes, Batista granted

an amnesty to Castro in 1955. Fidel journeyed to Mexico and came into the

company of the Argentinian physician, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. Fidel was soon convinced that

Che’s belief in armed insurrection was the only way to reform Cuba, and he

readily accepted Guevara’s offer to join him against Batista. On December 2,

1956, Fidel and his group tried again, this time with an assault on Manzanillo.

It is unclear whether he and his group really expected success with a

contingent of only 81 insurrectionists; if they did, they were sorely

disappointed.

Fidel and brother Raúl managed to escape into the

Sierra Madre, along with Che. From there, the group spent two years organizing

resistance and staging sorties against the government. Astonishingly, they even

managed to form something of a parallel government and institute some agrarian

reforms – mainly by organizing locals to take over land and manufacturing.

Batista’s forces seemed powerless, even with US assistance, to deter what was,

by now, a widespread popular reform initiative.

Coming to Power

Beginning in 1958, Fidel and his group took off the

gloves and began a series of military initiatives throughout the island. His

troops began to capture large chunks of the country and the popular movement

soon resulted in a wave of defections by Batista’s troops, causing the general

to flee to the Dominican Republic. With Batista’s government collapsed, Fidel

and his band of heroes marched into Havana in January 1959. An interim

government led by Jose Miro Cardona was sworn in; but in just a few weeks,

Cardona resigned and Castro was sworn in as prime minister.

Castro soon began wide-ranging reforms, which included

nationalizing factories and plantations. This move was intended to help end US

economic dominance on the island, but the US saw this only in a negative light,

causing friction between Cuba and the United States. Cuba declared that it

would compensate foreign companies, using the artificially low property values

that the companies themselves had negotiated with past Cuban governments in

order to keep their taxes low. This did not sit well with US corporations who suddenly thought their companies were much more valuable than they had been pretending.

At the time, Castro denied repeatedly that he was a communist

– remember, his Partido Ortodoxo was anti-communist – but many Americans thought

his policies looked like a Soviet-style control of the economy and government.

In April 1959, Castro visited the United States as a guest of the National

Press Club. President Dwight Eisenhower, however, refused to meet with him. It

is believed this snub, coupled with offers of assistance from the Soviet Union,

may have turned Castro from an ardent anti-communist, to a fervent socialist.

|

| La Habana

|

The US response to Cuba, which caused Fidel to lean

even more heavily on assistance and advice from the USSR, was provoked even

further by the US. In 1960, Cuba signed an agreement to purchase oil from the

Soviets, but the US-owned refineries on the island refused to process the oil.

So Castro expropriated them. The US retaliated by cutting sugar imports.

Bay of Pigs

On January 3, 1961, outgoing president Dwight

Eisenhower broke off diplomatic relations with Cuba. On April 16, Fidel formally

declared Cuba a socialist state. The following day, 1,400 Cuban exiles invaded

Cuba at Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) in an attempt to overthrow the Castro

government. It was an unqualified disaster. Hundreds of the insurgents were

killed and nearly 1,000 captured. The US denied involvement, but it soon became

clear the exiles were trained by the Central Intelligence Agency and armed by

the US. Years later, declassified material revealed the US had begun planning

an overthrow of Cuba as early as October 1959.

Although the Bay of Pigs invasion was conceived and

planned during the Eisenhower years, his successor, John Kennedy, gave it a

green light. What he refused to do, however, was grant the excursion any cover

from the US air force. There was nothing practical or humanitarian about this –

Kennedy was hoping to hide US involvement in the invasion. But that decision

did help to condemn the exercise to failure.

On May 1, Castro announced an end to democratic

elections in Cuba and denounced American imperialism. At the end of 1961, he declared

himself a Marxist-Leninist and stated that Cuba was adopting communist economic

and political policies. On February 7, 1962, the United States imposed a full

economic embargo on Cuba, a policy that continues more than 50 years later with a degree

of petulance that is almost laughable.

Missile Crisis

In October 1962, Castro’s increasing reliance on

Soviet aid brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. In an effort to deter

another US invasion of Cuba, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev arranged for the

placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba. Although he was clear that deterrence

was on his mind, Khrushchev justified the move as a response to American

missiles deployed in Turkey and pointed at Moscow.

Eventually, after many tense days, the world stood

down and fingers were removed from the nuclear buttons. The Cuban missiles

were dismantled, and the US missiles were removed from Turkey. In the West, this

is seen as a victory for Kennedy; elsewhere, it is recognized as a clever

strategy by Khrushchev who, even at home, had generally been considered to be a

buffoon.

It was a tense standoff between the two nuclear powers

that ultimately left Castro embarrassed. He was marginalized throughout the

crisis, and left out of the negotiations entirely. Worse, the US managed to

convince the Organization of American States that Cuba’s part in this

misadventure should result in the OAS ending diplomatic relations with Cuba.

|

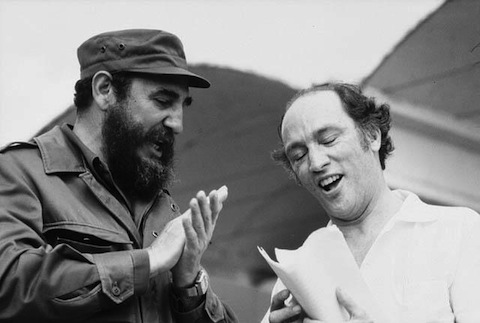

| Fidel & Canada's prime minister Pierre Trudeau. Fidel attended Trudeau's funeral in 2000, seated beside former US president Jimmy Carter

|

But Castro didn’t feel shame for long. In 1965, he

merged the Communist Party with his revolutionary organizations and installed himself

as head of the party. From that point onward, Fidel began a campaign of

supporting armed struggle against imperialism in Latin American and African countries.

By the 1970s, he was standing forward as the leading spokesperson for Third

World countries and providing military support to pro-Soviet forces in Angola,

Ethiopia, and Yemen. But despite heavy subsidization by the USSR, those Third

World efforts were largely unsuccessful and put a strain on the Cuban economy.

The US agreement that had ended the Missile Crisis –

not to invade Cuba - didn't prevent American ambitions of destroying Cuba in

other ways. Castro was the target of CIA assassination attempts over the years,

638 in all, according to Cuban intelligence. These ranged from exploding

cigars, to a fungus-infected scuba diving suit, to mafia-style shootings, among

others. Fidel took great delight in the fact that none of the attempts succeeded,

and frequently bragged about them. He was reported as saying that if avoiding attempted

assassination was an Olympic event, he would have many gold medals.

Since the revolution, many Cubans have fled Castro's

rule, mostly settling in Miami. The largest of these exodus movements occurred

in 1980 when Castro opened up the port of Mariel to allow exiled Cubans living

in Miami to come claim their relatives. Castro also loaded the ships with Cuban

prison inmates, mental patients, and other social undesirables. In all, about 120,000

Cubans have left their homeland for sanctuary in the United States.

Post-USSR

After the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union sent

Cuba's economy into a tailspin, Castro's revolution began to lose momentum.

Without cheap oil imports and an eager Soviet market for Cuban sugar and a few

other goods, Cuban unemployment and inflation grew. The contraction of the

Cuban economy resulted in 85 percent of its markets disappearing.

Yet Castro was very adept at keeping control of the

government during those difficult economic times. He pressed the United States

to lift the economic embargo, but it refused. So he adopted a quasi-free market

economy and encouraged international investment. He legalized the US dollar and

encouraged tourism, currently the greatest source of foreign income. Fidel also

visited the US in 1996 and invited Cuban exiles to return to Cuba to start

businesses.

Ill Health

In the late 1990s, Castro's advancing age started to

lead to speculation abroad – and probably at home – about his well-being.

Although health problems have been reported or rumoured over the years, the

most significant event was surgery for gastrointestinal bleeding in July 2006.

In a dramatic announcement, Castro designated his brother Raúl as the country's

temporary leader. Raúl had served as Fidel's second in command for decades, and

was officially selected in 1997 to be his successor. Although Fidel’s recovery

was prolonged, it appears the surgery was successful. Still, he could not run

away from time.

In February 2008, the now 81-year-old Fidel

permanently gave up the Cuban presidency. He handed over power to his 76-year-old

brother and the Cuban National Assembly officially elected Raúl Castro as

president of Cuba the same month, although Fidel retained his position as First

Secretary of the Communist Party. By April 2011, even that title was relinquished

- and Cuba was no longer Fidel.

In an article appearing on the Cuban government

website at the time, Fidel wrote that, "Raúl knew that at this time I

wouldn't accept any role in the party." He added that it is time for

younger party members to work on the country's economic system. "The new

generation is being called upon to rectify and change without hesitation everything

that should be rectified and changed," he wrote. In short, Fidel accepted

that not everything was perfect and he was comfortable with new people and new

ideas that would shore up the weaknesses.

Legacy

Now that Fidel has left us in body – has reached what

the US government euphemistically called “the biological solution” (having

failed so many times at less pleasant solutions) – it is time to realistically

evaluate the revolution’s successes and failures.

Even the most stalwart defenders of Castro and his

revolution would admit the legacy of Fidel is not perfect. To be sure, there have

been some instances where popular expression was oppressed. There have been

economic hardships, although it is entirely accurate to say much of this derives

from having a large swath of the world refuse to engage in trade with Cuba (at the behest of the US).

Boatloads of disaffected (or delusional) Cubans sailed off to Florida where a

few excelled, more became thugs and criminals, and the vast majority realized

the American Dream was just that – a dream, and you really need to be asleep to

believe it.

But Cuba is no North Korea. Although it is said by many abroad that Fidel has a huge ego and the

government revolves around him, it would do us well to remember that regardless

of the system or form of government, that is true almost everywhere. Cuba’s is

not a perfect system, but it is probably the only system that could have lifted

Cuba from its pre-revolutionary status as a brothel for rich Americans.

Fidel has delivered on many of the promises of his

revolution.

Cuba has a long history of domination by Spain, and

then the US, with a very short not-so-democratic period before Batista.

Although it can be reasonably argued that the system under Castro is not

democratic, he has nevertheless provided a society virtually free of racial

strife, with full medical and educational benefits for the people, with low infant

mortality and high life expectancy.

Castro's regime has been credited with opening more

than 10,000 new schools and increasing literacy to nearly 100 percent. Cubans

enjoy a universal health care system, which has decreased infant mortality to levels

not seen even in most First World nations - it is lower even than advanced countries like the US and Canada. Today, Cuba’s healthcare system is

so advanced that there is a thriving ‘medical tourism’ to the island from

foreign patients seeking good, effective, and inexpensive medical care.

Cuba is also now a net exporter of medical care. It has

twice as many physicians per capita as the United States, and its people are

able to access medical services and drugs at no, or very minimal, cost.

Capitalists might argue that this undervalues the physicians, but it is hard to

see how it does not benefit society as a whole. The Cuban medical system,

considered one of the world’s best, is delivered at an annual cost of less than

$400 per capita, compared to more than $6,000 in the US.

Cuba also donates medical expertise around the world,

especially in impoverished areas or disaster zones. Frequently, Cuban medical

personnel show up in earthquake and flood zones, usually without fanfare and

usually without any acknowledgement from the mainstream media of the West (note that when the Ebola outbreak of 2014 hit western Africa, the Cubans were there - this time, even some in the Western press acknowledged the Cuban sacrifice). They

even offer free medical training for students from disadvantaged areas of the

United States (and there are many of those, ‘American Dream’ notwithstanding),

provided they agree to return home and work in low-income neighbourhoods. While

the anti-socialists condemn this program, the mostly non-white female

Americans who benefit from this chance to learn and practice medicine are

grateful, and Cubans are justifiably proud of their contribution.

Pre-revolutionary

Cuba was rife with privilege for

whites or descendants of the Spaniards, and so they were the ones who

left during the waves of immigration. But now there is a level of race

and gender

equality in Cuba that is rare in the world. Fidel’s principle of equal

pay and

equal opportunity is woven throughout the social fabric of the island so

that

people of almost any skin shade and both sexes are liable to be found

doing

almost any job or holding almost any position.

By North American standards, most Cubans don’t live in

fancy places. But no one is homeless. If, as frequently happens, homes are lost

to hurricanes, the government rebuilds at no cost to the survivors. And, as a

mark of superb social planning, it is very rare for Cubans to be killed during

these annual storms - the 2005 and 2012 onslaught of Hurricanes Dennis and Sandy were stark reminders of the humbling power of Nature. The early warning and protection system leaps into action

and people head for designated shelters. Try comparing that to any other country,

including the wealthiest, where people survive, or not, based on their own wits and luck.

One of the country’s finest achievements is its environmental

progress. Much of this has been driven by necessity, but Cuba is the only

country in the world to have converted entirely to organic agriculture. And it

did this in fewer than 10 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union ended

financial assistance to the island.

During this rebuilding period, when $4-$6 billion in annual funding vanished, Castro implemented a program known as the ‘Special

Period in Time of Peace’. This essentially meant enduring wartime scarcities

without the war. But in less than a decade, food crops were developed without

the need for significant chemical inputs or heavy machinery, unused land was

converted to growing food, a program of urban agriculture was implemented to

supplement the farmers.

By 1999, the Grupo de Agricultura Organica that

spearheaded the conversion was given the Right Livelihood Award – recognized

worldwide as the “alternative Nobel”.

When the loss of Soviet assistance made gasoline a

rare commodity, Castro purchased or built bicycles. Even today, these are

plentiful on Cuban roads, leading to a lower transportation cost, healthier

citizens, and cleaner air. Even as gasoline has become more plentiful (thanks

in large part to trade with Venezuela), the law requires that drivers pick up

hitchhikers and carry as many people as the vehicle will hold.

Cuba's system has obvious flaws, obvious even to them. And they are experimenting with changes that will improve the lives of the people while holding true to the socialist paradigm.

But in considering

whether the people as a whole are better off since Castro, it would be hard to

reach a conclusion that Batista and his ilk would be preferable. Many charges leveled

against Fidel by the West – suppression of dissent, torture of enemies,

dealings with bad actors on the world scene – are exaggerated and distortions

of the truth, or even manufactured lies. But even if true, there are few world leaders about whom the same

could not be said.

It is true that Cubans didn’t enjoy freedom to travel abroad

under Fidel, but one could argue everyone’s labour was needed and the fear of

losing people en masse offered some justification for that policy. Still, it

has been revised and there is now more ability for Cubans to travel.

But the thawing of relations continues. Cuba has no illusions that the US has suddenly become decent and honourable - they know better. But there are some changes already in place and more to come that will benefit Cuba. It is hard to believe the US is looking for anything other than another vassal state.

There has never been any groundswell movement in Cuba

to reject Castro’s revolution. Surely there are some who are not happy; but the

majority appears to believe Cuba is much better off now than before Fidel. Some

might argue that an uprising is virtually impossible with Castro’s tight

control; but how would they explain, then, the overthrow of the US-supported

Batista with a mere 180 men? A popular revolt has not taken place because,

well, the idea isn’t popular.

It is hard to deny the almost 100% level of literacy,

greater even than most First World nations. Castro opened thousands of schools,

and even now the lowest peasant gets education no matter how far he or she

lives from a local school. If they can’t come to the school, the school comes

to them.

Perhaps

the greatest Castro legacy is the object lesson that a small band of very

determined people could overthrow a government supported by the world’s greatest

bully, and then maintain power in the face of both military and economic

calumny from that same bully. For more than half a century.

If

nothing else, Fidel Castro Ruz serves as a beacon to all those nations and

peoples who believe they are at least as important to this planet as the Americans

of the United States.

Epilogue:

The world was caught off guard by the December 18, 2014 announcement from Washington and Havana of a new era in relations between the US and Cuba. Both Presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro took the opportunity to thank Canada for mediating secret talks between the two nations that had occurred over the previous 18 months or so. [Canada was a reasonable choice as convener since it is friends with both of them.]

Most commentators seemed to think this was a good thing, and a measure long overdue. While there are at least a few members of US Congress who had a problem with the agreement (and no doubt Raúl Castro had similar gripes from his government), there was also wide ranging opinion about the value of the agreement and, more importantly, who won and who lost.

There were some in the US who characterized Obama as a sell-out and who noted it would still take an act of Congress for the US embargo on Cuba to be lifted. And there were those who believe the deal was a slap in the face to various others: to Russia; to ALBA; to Mercosur, and so on - a slap by Cuba.

Commenting

on the apparent thaw, Fidel cautiously welcomed it but was clear that

he remains suspicious of American intent. Through long experience, he

learned that the US is not to be trusted - a lesson many other nations

overlooked at their peril.

Whatever reasons the two countries might have had for heading down this path at this time (or, rather, starting down it 18 months earlier), it was sure to take some time before it can be said with clarity whether either side gained or lost anything.

Cuba stated clearly that its expectation was for the US to respect the government of Cuba and to refrain from interfering in Cuban society. For its part, the US quickly divided into camps. Capitalists began to salivate over a new market, with cheap labour; Cuban exiles began either to dream of a return home, or were rabidly opposed to this rapprochement so long as either Castro brother remained alive; President Obama's political opponents objected because, well, that's what they always do.

And then Obama shot himself in the foot. On March 9, 2015, he decided to declare - beyond any sensible reasoning - that Venezuela represented an imminent risk to US national security. Where that came from is speculative, but Cuba was quick to argue that Obama's move was nonsense, to condemn it outright, and to hint that any deal involving the US and Cuba might revolve around the US keeping its grubby mitts off Venezuela.

Cuba and Venezuela are allies and both members of several Latin American coalitions. But perhaps even more importantly, Castro might be speculating that he was being misled - that the US wasn't trying to eliminate its embargo, they simply wanted to transfer it to a new contender.

Nevertheless, talks and trade visits continued, embassies opened - but still no lifting of the embargo. Raúl indicated he would retire at the end of his current term and his successor will have to navigate what is sure to be an exercise in arm-twisting and deceit from the US. In the end, it seems likely that Fidel's skepticism about the US overtures was well placed.

Obama then became the first sitting US president to visit Cuba in more than 50 years, in March 2016. He spent a couple of days, some of it undoubtedly uncomfortable for him. For despite his 'friendly' hints at 'human rights abuses' in Cuba, it was made clear to him that he was not persuading the government. It was also made clear to him that the US is on very shaky ground criticizing any other country's 'human rights'.

Obama's host (Raúl Castro) stated in public that Cuba welcomed the visit and that better relations with the US was in everyone's interest. But he also stated plainly that Cuba has no intention of changing its form of government or its society to suit the US.

Oh yes, and there was still no lifting of the embargo.

Fidel and his revolution were still alive, and still winning.

Paul Richard Harris is an Axis of Logic editor and columnist, based in Canada. He can be reached at paul@axisoflogic.com.

Read the Biography and additional articles by Axis Columnist, Paul Richard Harris

© Copyright 2016 by AxisofLogic.com

This material is available for republication as long as reprints include verbatim copy of the article in its entirety, respecting its integrity. Reprints must cite the author and Axis of Logic as the original source including a "live link" to the article. Thank you!

|