|

“You’re sitting on a gold mine” is supposed to mean you have a great opportunity to become really wealthy.

The Indigenous Ipili people of the highland Enga Province of Papua New Guinea have literally been sitting on a gold mine for millennia. But instead of bringing wealth, the mine in the Porgera River region has been a curse.

|

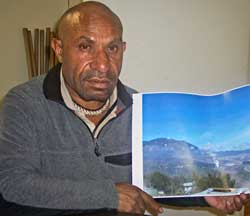

| Jethro Tulin, leader of Ipili community

in Papua New Guinea, shows location

of Barrick’s gold mine.

John Catalinotto |

Jethro Tulin, a leading Papua New Guinea trade unionist and Indigenous leader, says the gold mine sucking that mineral wealth out of Porgera has destroyed his people’s ancient subsistence farming community and brought nothing worthwhile in return. Tulin was in New York this May attending a United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. He spoke for the Akali Tange Association, which represents around 10,000 Indigenous “landowners” in the mine area.

Two decades ago, Tulin became the first secretary general of the Mine and Allied Workers Union, which at that time represented as many as 3,000 miners and construction workers at the Porgera mine.

Despite Porgera’s remote location, its story is familiar. From Dakota’s Black Hills to the Western Shoshone to the Pascua- Lama project on the Chile-Argentina border, brutal exploitation of Indigenous peoples and their lands by transnational corporations is notorious.

Papua New Guinea consists of the eastern half of New Guinea, the second-largest island in the world, plus some smaller islands. The western half is part of Indonesia. Papua New Guinea’s 6.4 million people live on a territory larger than California. With about 1,000 ethnic groups and more than 800 languages, few lands are more diverse.

Dutch, German and British imperialism have had their presence on the island. After World War I Papua New Guinea became an Australian “protectorate” and remained so until it became nominally independent in 1975.

“We have had contact with the rest of the world for only the last 70 years,” Tulin told Workers World. “The first Europeans reached the Porgera valley in the 1930s. That’s when we learned to pan for gold in the Porgera River to supplement income beyond subsistence farming and pig-raising.

“We are organized by family, clan, tribe, etc., with land property passed down to the children. Papua New Guinea law officially recognizes these land holdings—although there are no written titles. But the government put in some ‘small print’ in that law: the people own only the first six feet below the surface of the land. That means the government can lease mining rights for below six feet to transnational companies.

“The Porgera mine was leased first to the Placer Dome Corp., which was in turn taken over by Barrick, also a Canada-based mining corporation that is the largest miner of gold in the world. There are a number of ancestral villages within the mine area, which covers some nine square miles of land.”

Barrick shoots people for ‘stealing’ gold

“Our organization is demanding a fair relocation process for the residents. We want Barrick to repair the damage to the environment. We want reparations to compensate for those who have been killed or injured by the mine’s security force.

“According to the agreement and by international law, the mining company is responsible for the costs of voluntarily resettling the people. Instead, the mine management allowed the people to stay on the land in the open-pit mine area. The waste tailings from the gold mine, dumped directly into the water from the mill, have ruined the farming in the area and made much of the population unable to survive on farming alone.

“Adding to the impoverishment,” Tulin continued, “Barrick uses force to stop the local people from finding small amounts of gold, as they did before the mine was built. Barrick’s security force, recruited from outside the district, has shot and killed people who, the cops say, are ‘stealing’ Barrick’s gold when they scoop up the ore on the edges of the pits—it’s no longer possible to pan the polluted river.

|

| Police, acting for Barrick, set hundreds of

Porgera, Papua New Guinea, homes on fire

April 27.

Akali Tange Association |

“The company says that its lease means the locals are ‘trespassing’ and the mine ‘owns’ the gold. The security force, besides killing five people in the past year alone, has raped women in the area.”

Amnesty International, in a report criticizing Barrick, points out that in 2008 Barrick mined 627,000 ounces of gold at Porgera, which that year was worth more than half a billion dollars. Since limestone, water and gas for electricity are all nearby, production costs are low at the mine, and the profits leave more than enough to buy influence in any country.

“To show the relationship between the transnational mining corporation and the Papua New Guinea and regional governments, consider this: mine security will bring the person they shot to the nearby hospital, but mine management will prevent the local and Papua New Guinea police homicide squad from investigating on mine land,” Tulin said.

Besides the U.N. meeting, Tulin was also in North America to attend and shake up the shareholders’ meeting of Barrick in Toronto at the end of April. There, holding a proxy that gave him a voice, for the second year in a row he read a series of demands on this giant gold-mining corporation, which owns 27 mines and development projects in Canada, the U.S., Chile, South Africa, Australia, Peru and Russia.

Tulin told Barrick’s management at the April 29 meeting: “The toxic waste you continue to dump into our 800-kilometer-long river system—which would be illegal in Canada—has caused the Norwegian government to divest its pension fund from more than 230 million Canadian dollars worth of shares in Barrick Gold and to report that its decision was based on its ‘assessment that investing in the company entails an unacceptable risk of the Fund contributing to serious environmental damage.’”

While Tulin was in Canada, the Papua New Guinea government launched an assault on his people in Porgera under the name of “Operation Ipili 2009.” Using the pretext of “eliminating illegal miners,” that is, people who scavenge gold particles, Papua New Guinea police burned over 200 homes in the village of Ungima alone.

“Now, under the influence of your company,” Tulin continued, “the Papua New Guinea government has imposed a virtual State of Emergency in Porgera. When I came to Canada last week I received reports from Porgera that landowners who have spoken out against your mine are now being targeted. This week, and while I am standing here before you, their houses are being burnt down and they are fleeing for fear of their life,” he told the company officials. (protestbarrick.net)

“The government’s priority,” Tulin said to WW, “should be to protect the interest of the people, but instead it is protecting the interest of those who come in with money and who are destroying the traditional way of life. We are getting no benefit from development.”

Tulin is also exploring the possibility of bringing a civil suit within U.S. courts against Barrick, which has an office in New York and a mine in Nevada. The latter is being protested by the Great Basin Resource Watch and the Western Shoshone people. U.S. laws allow such a suit, while Canadian laws don’t. His group has support from environmental and Indigenous organizations in the U.S. and Canada.

Sergio Campusano, president of the Diaguita Huascoaltinos Indigenous people in Chile, was also at Barrick Gold’s annual meeting in Toronto protesting the damage to the environment the Pascua Lama mine is causing in that region, including the removal of most of three glaciers that feed fresh-water rivers.

Struggle in Bougainville

A struggle by the people of Bougainville Island, part of Papua New Guinea but now with an autonomous government, against the Rio Tinto mining company led to a decade-long independence war and 15,000 deaths. The struggle ended in a defeat for Rio Tinto, the Papua New Guinea central government and the Australian overlords. Rio Tinto was driven out of Bougainville, but the mining company never paid the reparations the people deserved.

Claims against Rio Tinto are still in U.S. federal court, after the company’s legal maneuvers delayed the original suit.

Tulin has said he would like to win the peoples’ just demands without the same heavy casualty rate and with Barrick staying long enough to pay its debt to the Ipili and other peoples.

The recent aggression by the central government and police against the population of Porgera has begun to awaken worldwide solidarity with the Ipili and other people of Papua New Guinea’s Enga province, whose struggle to survive is part of the overall battle against world imperialism and its threats against peace, environment and the world itself.

Workers World

|