|

By Murat Kurnaz

Star Tribune

Sunday, Jan 15, 2012

|

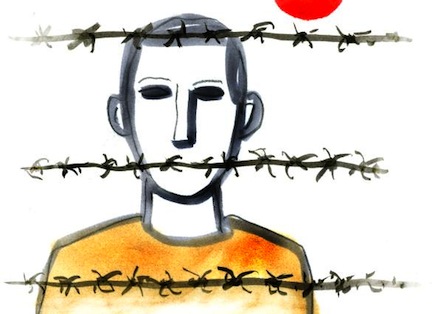

I left Guantanamo Bay much as I had arrived almost five years earlier -- shackled hand-to-waist, waist-to-ankles, and ankles to a bolt on the airplane floor.

My ears and eyes were goggled, my head hooded, and even though I was the only detainee on the flight this time, I was drugged and guarded by at least 10 soldiers. This time though, my jumpsuit was American denim rather than Guantanamo orange.

When we landed, the American officers unshackled me before they handed me over to a delegation of German officials. The American officer offered to reshackle my wrists.

But the commanding German officer strongly refused: "He has committed no crime; here, he is a free man."

Strange, I thought, as I stood on the tarmac watching the Germans teach the Americans a basic lesson about the rule of law.

We've just marked the 10th anniversary of the opening of the detention camp at the American naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

I am not a terrorist. I have never been a member of Al-Qaida nor supported them. I don't even understand their ideas.

I am the son of Turkish immigrants who came to Germany in search of work. In 2001, when I was 18, I married a devout Turkish woman and wanted to learn more about Islam and to lead a better life. I did not have much money.

Some of the elders in my town suggested that I travel to Pakistan to study the Qur'an with a religious group there.

I made my plans just before 9/11. I was 19 then and was naive and did not think war in Afghanistan would have anything to do with Pakistan or my trip there.

I was in Pakistan, on a public bus on my way to the airport to return to Germany when the police stopped the bus. I was the only non-Pakistani on the bus -- the police asked me to step off to look at my papers and ask some questions.

The police detained me but promised they would soon let me go to the airport. After a few days, the Pakistanis turned me over to American officials.

At this point, I was relieved to be in American hands; Americans, I thought, would treat me fairly. I later learned the United States paid a $3,000 bounty for me.

I didn't know it at the time, but apparently the United States distributed thousands of fliers all over Afghanistan, promising that people who turned over Taliban or Al-Qaida suspects would, in the words of one flier, get "enough money to take care of your family, your village, your tribe for the rest of your life."

A great number of men wound up in Guantanamo as a result.

I was taken to Kandahar, in Afghanistan, where American interrogators asked me the same questions for several weeks: Where is Osama bin Laden? Was I with Al-Qaida?

No, I told them, I was not with Al-Qaida. No, I had no idea where Bin Laden was.

They dunked my head under water and punched me in the stomach; they don't call this waterboarding, but it amounts to the same thing. I was sure I would drown.

At one point, I was chained to the ceiling and hung by my hands for days. The pain was unbearable.

After about two months in Kandahar, I was transferred to Guantanamo. There were more beatings, solitary confinement, freezing temperatures and extreme heat, days of forced sleeplessness.

The interrogations continued, always with the same questions. Nothing I said satisfied them.

I looked for ways to feel human. I have always loved animals. I started hiding a piece of bread from my meals and feeding the iguanas that came to the fence. When officials discovered this, I was punished with 30 days in isolation and darkness.

I remained confused on basic questions: Why was I here? With all its money and intelligence, the United States could not honestly believe I was Al-Qaida, could they?

After two and a half years at Guantanamo, in 2004, I was brought before what officials called a Combatant Status Review Tribunal, at which a military officer said I was an "enemy combatant" because a German friend had engaged in a suicide bombing in 2003 -- after I was already at Guantanamo.

I couldn't believe my friend had done anything so crazy but, if he had, I didn't know anything about it.

A couple of weeks later, I was told I had a visit from a lawyer. They took me to a special cell, and in walked an American law professor, Baher Azmy. He did not believe the evidence against me and quickly discovered that my "suicide bomber" friend was, in fact, alive and well in Germany.

Azmy, my mother and my German lawyer helped pressure the German government to secure my release. Recently, Azmy made public American and German intelligence documents from 2002 to 2004 that showed both countries suspected I was innocent.

Now, five years after my release, I am trying to put my memories behind me.

Still, it is hard not to think about my time at Guantanamo and to wonder how it is possible that a democratic government can detain people in intolerable conditions and without a fair trial.

* * *

Murat Kurnaz is the author of "Five Years of My Life: An Innocent Man in Guantanamo." He wrote this article for the New York Times.

Source URL

Print This Print This

|