Antibiotics were once the wonder drug. Now, however, an

increasing number of highly resistant -- and deadly -- bacteria are

spreading around the world. The killer bugs often originate in factory

farms, where animals are treated whether they are sick or not.

|

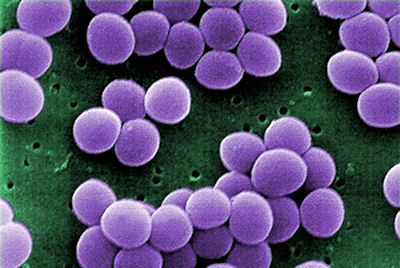

| An image of a strain of a Staphylococcus aureaus bacteria: Researchers around the world are growing increasingly worried about news strains of bacteria that are resistant to most common antibiotics. |

The pathogens thrive in warm, moist environments. They feel

comfortable in people's armpits, in the genital area and in the nasal

mucous membranes. Their hunting grounds are in the locker rooms of

schools and universities, as well as in the communal showers of prisons

and health clubs.

The bacteria are transmitted via the skin, through towels, clothing or

direct body contact. All it takes is a small abrasion to provide them

with access to a victim's bloodstream. Festering pustules develop at the

infection site, at which point the pathogens are also capable of

corroding the lungs. If doctors wait too long, patients can die very

quickly.

This is precisely what happened to Ashton Bonds, a 17-year-old

student at Staunton River High School in Bedford County, in the US state

of Virginia. Ashton spent a week fighting for his life -- and lost.

This is probably what also happened to Omar Rivera, a 12-year-old in New

York, who doctors sent home because they thought he was exhibiting

allergy symptoms. He died that same night.

The same thing almost happened at a high school in the town of Belen,

New Mexico. Less than two weeks ago, a cheerleader at the school was

hospitalized after complaining about an abscess. Twelve other female

students had been afflicted with suspicious rashes. All the students

tested positive for a bacterium that the US media has dubbed the

"superbug."

The school administration in Belen believes that the bacterium was

spread on mats in the school's fitness and wrestling rooms. The facility

was thoroughly disinfected 40 times, and yet the fear remains.

|

| A MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria strain is seen in a petri dish: Less than a century after the discovery of penicillin, one of the most powerful miracle weapons ever produced by modern medicine threatens to become ineffective.

|

Fears of a Pandemic

Microbiologists refer to this bacterium as community-acquired

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or ca-MRSA. The terrifying

thing about it is its resistance to almost all common antibiotics, which

complicates treatment. And, in contrast to the highly drug-resistant

hospital-acquired MRSA (ha-MRSA) strains, which primarily affect the

elderly and people in hospitals and nursing homes, ca-MRSA affects

healthy young people. The bacterium has become a serious health threat

in the United States. Doctors have already discovered it in Germany,

although no deaths have been attributed to it yet in the country.

The two bacteria, ha-MRSA and ca-MRSA, are only two strains from an

entire arsenal of pathogens that are now resistant to almost all

available antibiotics. Less than a century after the discovery of

penicillin, one of the most powerful miracle weapons ever produced by

modern medicine threatens to become ineffective.

The British medical journal The Lancet warns that the

drug-resistant bacteria could spark a "pandemic." And, in Germany, the

dangerous pathogens are no longer only feared "hospital bugs" found in

intensive care units (ICUs). Instead, they have become ubiquitous.

|

| Some 900 metric tons of antibiotics are administered to livestock each year in Germany alone. Instead of treating only those animals that are truly sick, farmers routinely feed the medications to all of their animals. Likewise, some 300 metric tons of antibiotics are used to treat humans each year, far too often for those merely suffering from a common cold. This large-scale use inevitably leads to the spread of more resistant bacteria. |

About two weeks ago, consumers were alarmed by the results of an

analysis of chicken meat by the environmentalist group Friends of the

Earth Germany (BUND), which found multidrug-resistant bacteria on more

than half of the chicken parts purchased in supermarkets.

The dangerous bacteria have even been detected on one of Germany's

high-speed ICE trains. Likewise, more than 10 percent of the residents

of German retirement homes have been colonized by MRSA bacteria. In

their case, every open wound is potentially deadly. The pathogens have

also been found on beef, pork and vegetables.

Another alarming finding is that about 3 to 5 percent of the

population carries so-called ESBL-forming bacteria in the intestine

without knowing it. Even modern antibiotics are completely ineffective

against these highly resistant bacteria.

Diminishing Defenses

When the neonatal ICU at a hospital in the northern German city of

Bremen was infested with an ESBL-forming bacterium last fall, three

prematurely born babies died.

Infestation with multidrug-resistant bacteria is normally harmless to

healthy individuals because their immune systems can keep the pathogens

under control. Problems arise when an individual becomes seriously ill.

"Take, for example, a person who is having surgery and requires

artificial respiration and receives a venous or urinary catheter,"

explains Petra Gastmeier, director of the Institute of Hygiene and

Environmental Medicine at Berlin's Charité Hospital. "In such a case,

the resistant intestinal bacteria can enter the lungs, the bloodstream

and the bladder."

This results in urinary tract infections, pneumonia or sepsis, which

are increasingly only treatable with so-called reserve antibiotics, that

is, drugs for emergencies that should only be administered when common

antibiotics are no longer effective.

The Spread of Killer Bugs

Recently, an even greater threat has arisen. With the spread of

ESBL-forming bacteria, reserve antibiotics have to be used more and more

frequently, thereby allowing new resistances to develop. In fact, there

are already some pathogens that not even the drugs of last resort in

the medical arsenal can combat.

In India, where poor hygiene and the availability of over-the-counter

antibiotics encourage the development of resistance, an estimated 100 to

200 million people are reportedly already carriers of these virtually

unbeatable killer bacteria. There is only one antibiotic left -- a drug

that is normally not even used anymore owing to its potentially fatal

side effects -- that is still effective against these killer bacteria.

In serious cases, people who become infected with these types of

pathogens die of urinary tract infections, wound infections or

pneumonia.

The killer bugs have also reached England, presumably through medical

tourists who traveled to India for cosmetic surgery, and they have

reportedly already infected several hundred people. A few cases have

also turned up in Germany.

Israel even experienced a nationwide outbreak a few years ago. Within

a few months, about 1,300 people were afflicted by an extremely

dangerous bacterium that killed 40 percent of infected patients. Even

today, the same bacterium still sickens some 300 people a year.

Part 2: The Post Antibiotic Era

This rapid spread has caused many to wonder whether more and more

people in Germany will soon die of infectious diseases that were

supposedly treatable, as happened in centuries past. Unfortunately,

there are many indications that this might ultimately be the case.

"We are moving toward a post-antibiotic era," predicts Yehuda Carmeli

of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. "But it won't happen on one

day or at the same time in every part of the world. And that's the

tragedy, because this means that it is not perceived as a serious

problem."

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently warned against an impending medical catastrophe. And, in The Lancet,

leading healthcare experts published an urgent appeal: "We have watched

too passively as the treasury of drugs that has served us well has been

stripped of its value. We urge our colleagues worldwide to take

responsibility for the protection of this precious resource. There is no

longer time for silence and complacency."

In fact, the carelessness with which doctors and farmers are

jeopardizing the effectiveness of one of the most important groups of

drugs borders on lunacy. Some 900 metric tons of antibiotics are

administered to livestock each year in Germany alone. Instead of

treating only those animals that are truly sick, farmers routinely feed

the medications to all of their animals. Likewise, some 300 metric tons

of antibiotics are used to treat humans each year, far too often for

those merely suffering from a common cold.

A Foe We Helped Become More Flexible

This large-scale use inevitably leads to the spread of resistant

bugs. Indeed, antibiotics offer ideal growth conditions to individual

bacteria that have naturally become resistant through a small change in

their genetic makeup. Simply put, they benefit from the fact that the

antibiotics still kill off their competitors, the non-resistant

bacteria.

In many cases, a genetic mutation isn't even necessary to allow a

resistant bacterium to develop. Bacteria can incorporate bits of genetic

material from other pathogens. For example, for millions of years, the

gene for ESBL resistance lay dormant in the ground, where it was part of

a complicated ecosystem of bacteria, penicillin-producing fungi and

plant roots. Again and again, the gene was incorporated by human

intestinal bacteria -- as useless ballast. It was only the large-scale

use of antibiotics that provided the ESBL-forming bacteria with the

opportunity to proliferate.

Recent studies show that quantities of antibiotics much smaller than

previously thought can lead to the development of resistance. In

retrospect, the uncontrolled dispensing of antibiotics has proven to be a

huge mistake. "In the last 30 years, we have contaminated our entire

environment with antibiotics and resistant bacteria," says Jan

Kluytmans, a microbiologist at Amphia Hospital, in the southern Dutch

city of Breda. "The question is whether this is even reversible anymore.

Perhaps we can prevent only the worst things from happening now."

Shocking Levels of Antibiotic Abuse on Farms

Since a large share of resistant bacteria come from barns, it will be

critical to drastically reduce the use of antibiotics in agriculture.

Remarkably often, farmers, feedlot operators and veterinarians are

themselves carriers of multidrug-resistant bacteria. Kluytmans has even

demonstrated that the pathogens found in humans are very often

genetically identical with the bacteria detected on meat.

It's virtually impossible to become infected by eating such meat, at

least as long as it's well-cooked. The risk arises when raw meat comes

into contact with small wounds. What's more, even vegetable crops can

become contaminated when liquid manure is spread onto fields.

The exhaust gases emitted by giant feedlots for pigs and chickens

could also pose a danger greater than previously thought. These meat

factories blow bacteria, viruses and fungi into the air. The government

of the western German state of North Rhine-Westphalia has commissioned a

study to determine whether feedlots are discharging multidrug-resistant

bacteria, thereby endangering people in the surrounding areas.

Last year, North Rhine-Westphalia was also the first German state to

systematically investigate the use of antibiotics in chicken farms. The

horrifying conclusion was that more than 96 percent of all animals had

received these drugs -- sometimes up to eight different agents -- in

their short lives of only a few weeks. "That was the proof that the

exception -- namely, treating disease -- had become the rule," says

Johannes Remmel, a Green Party member and the state's consumer

protection minister.

Abysmal Feedlot Conditions

As the results of the investigation suggest, factory farming is to

blame. The bigger an operation, the more antibiotics are administered to

individual animals. Investigators also noted that the duration of

antibiotic use was usually very short -- shorter than specified in the

licensing requirements. This saves money, but it also promotes the

formation of resistance.

The fact that livestock farmers mix antibiotics into feed has to do with production conditions in feedlots:

- To produce veal, animals from different sources that are too weak

for milk and beef production -- and likewise more susceptible to

infectious diseases -- are often jammed into enclosures.

- Pigs are usually kept in very small spaces, making them very

aggressive and causing them to fight. Their wounds have to be treated

with antibiotics.

- In the past, it took 80 days until a chicken was ready for

slaughter. Today it's only 37 days. Chicken farmers have a profit margin

of only a few cents per animal. To minimize losses through disease,

poultry producers and their veterinarian helpers use antibiotics as a

preventive tool.

However, factory farming is also possible without the uncontrolled

use of antibiotics. Dairy cows, for example, are usually not given these

drugs since antibiotics would interfere with the production of cheese

and yogurt. Nevertheless, there are still plenty of inexpensive milk

products on supermarket shelves.

"In the Netherlands," says Kluytmans, "the use of antibiotics in

feedlots was even reduced by about 30 percent within two years -- partly

as a result of stricter regulations for veterinarians. That's more than

we administer to humans." Unfortunately, he adds, the use of

antibiotics in feedlots is practically a matter of religious belief.

Efforts to Combat Antibiotics Abuse

In early January, Ilse Aigner, Germany's minister of food,

agriculture and consumer protection, unveiled a package of measures

aimed at curbing the use of antibiotics in farm animals. The measures

include stricter controls that would make it more difficult to add

antibiotics urgently needed in human medicine to animal feed. Germany's

federal government is also considering suspending veterinarians' right

to dispense medicine. In contrast to doctors practicing medicine on

humans, who prescribe drugs to be purchased at pharmacies, veterinarians

can even directly sell drugs to farmers and feedlot owners, which means

they stand to profit handsomely from the large-scale use of

antibiotics.

However, Remmel, the consumer protection minister of North

Rhine-Westphalia, believes that Aigner's proposals are "deceptively

packaged," and he is calling for exact specifications on the amounts of

antibiotics that can be used.

Similarly, there is also little control over the use of antibiotics

in human medicine. In Germany, in particular, doctors prescribe

antibiotics as they see fit, whereas in the Netherlands doctors must

first consult with a microbiologist.

"Just as in pain therapy, there really ought to be experts for

treatment with antibiotics," says Gastmeier, the director of the

Institute of Hygiene and Environmental Medicine at Berlin's Charité

Hospital "But young doctors, in particular, are often relatively

uninformed." Indeed, in medical school, they learn very little about the

proper use of antibiotics.

Little Research into New Antibiotics

Still, even more responsible prescribing practices will hardly be

able to stop the advance of resistant bacteria in the long term. What's

more, no new antibiotics can be seen on the horizon. Only four

pharmaceutical companies worldwide are still working on developing new

agents.

"Antibiotics have a serious problem," says Wolfgang Wohlleben of the

Institute of Microbiology at the University of Tübingen, in southwestern

Germany: "They actually work." Indeed, the drugs can get the better of

an infection within a few hours or days, and then they are no longer

needed. By contrast, patients taking drugs to fight high blood pressure

or diabetes often have to take them for the rest of their lives -- which

translates into steady, reliable profits for pharmaceutical companies.

Yet another factor making antibiotic-related R&D unattractive is

the fact that doctors can only prescribe a new antibiotic in the most

extreme of emergencies lest it lose its efficacy within a short amount

of time.

Given these circumstances, major pharmaceutical companies stopped

searching for new antibiotics years ago. Nowadays, only small start-ups

or university-based researchers are interested in the field.

Abandoned by Big Pharma

In reality, the search for new drugs should be getting easier rather

than more difficult. In the 1990s, the large pharmaceutical companies

spent several million euros searching for weaknesses in the genetic

makeup of bacteria. But although the researchers were actually

successful, the subsequently developed drugs never made the final leap

into clinical use.

"In the end, the risks of antibiotic research were simply too great

for companies," says pharmacist Julia Bandow, who went into academia to

continue studying antibiotics after working for the US-based

pharmaceutical giant Pfizer for six years.

But without the large pharmaceutical companies, there can be little

hope of progress. After all, testing a drug in human subjects takes

years and costs millions. And, as Bandow says of her fellow academics,

"We can't do it alone."

If pharmaceutical companies refuse to invest in the necessary

studies, it's critical for the government to step in. At the least,

politicians could make the development of antibiotics more attractive,

for example, by extending the time before patents expire so as to allow

companies to earn returns on their investments for longer. But, so far,

these are all nothing but ideas.

"At some point in the coming years," says microbiologist Kluytmans,

"there will be a disaster involving resistant pathogens with many

casualties. Only then will something change."

BY PHILIP BETHGE, VERONIKA HACKENBROCH, LAURA HÖFLINGER, MICHAEL LOECKX and UDO LUDWIG

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan

Source: Der Spiegel