|

|

|

By Laura Carlsen, FPIF

Foreign Policy in Focus

Monday, Aug 3, 2015

|

| Prosters rally in Mexico City for the ouster of President Enrique Pena Nieto. (Photo: Montecruz Foto / Flickr) |

Over 90 percent of Mexicans have lost faith in their political parties. What comes next? If Washington gives the Mexican president a pat on the back, it will be a stab in the back for the Mexican social movement for justice and transparency.

After the polls closed in Mexico on June 7, embattled President Enrique Peña Nieto stepped up to claim a victory that he didn’t win.

“In Mexico, democracy advances,” he declared triumphantly in a polished television address. He announced that the Mexican people had expressed their will through institutions and channeled their differences through the democratic system.

Though there are calls throughout Mexico for the president to step down, there was nothing conciliatory about his speech. He called the voter turnout — which fell just under 50 percent — a “mandate to reject violence and intolerance and work together toward prosperity and peace.” He touched only obliquely pre-electoral conflicts over protesting teachers, disappeared students, and other controversies. He threw down the gauntlet to the thousands who have protested neoliberal educational and privatization reforms by concluding: “The reforms are going forward.”

But in reality, the results of the elections were far from a vote of confidence for Peña Nieto’s government — or even for the electoral system itself.

Punishment of the Major Parties

With more than 2,000 posts up for grabs — including the whole lower house of Congress and nine governorships — Mexicans turned out at a rate of around 48 percent. That’s high for a midterm, when the presidency isn’t up for a vote.

Yet that participation hasn’t dissipated discontent. Mexico’s incoming politicians will face as much — or even more — protest and mistrust as the old ones. Polls showed that an astounding 91 percent of those surveyed don’t trust the political parties, and only 27 percent are satisfied with the level of democracy in Mexico.

In other words, people voted even when they had little faith in the system or the results. In some cases voters might’ve had real enthusiasm for candidates, but in others people opted for the lesser of evils, took money for votes, or were coerced by employers. To interpret that as a unified statement in support of institutions that most people believe are corrupt is a purposeful error designed to paper over deep and growing dissent.

All the major parties — the governing Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the right-wing National Action Party (PAN), and the left-of-center Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) — suffered setbacks.

The PRI lost around a dozen seats in the Chamber of Deputies, though it will still control a majority of seats thanks to a coalition with the Green and New Alliance Parties. Peña Nieto took the result as an endorsement of his administration, yet polls show that 85 percent of Mexicans don’t trust the president, and 60 percent believe that corruption has increased during his administration. So continued PRI control could actually raise the temperature of the pressure pot Mexico is rapidly becoming.

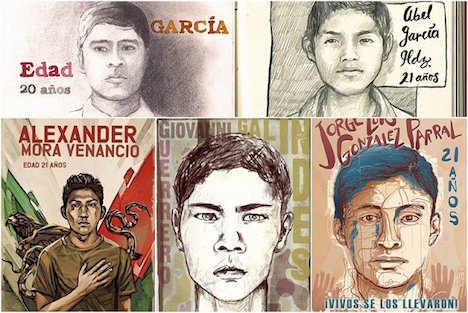

Peña Nieto has suffered months of bad press. Investigators published exposés about a mansion purchased for his family by a major government contractor, and other dubious dealings have affected him and members of his administration. His popularity plummeted after his administration first ignored then blocked an investigation into the case of the 43 missing students of Ayotzinapa and alleged extrajudicial executions in Tlatlaya. To top it off, the economic outlook for Mexico has been repeatedly readjusted downward since the year began.

|

| Mexico's Undead rise up |

The conservative PAN maintained its level of about 20 percent of the national vote. It will govern in Baja California Sur and the central state of Queretaro.

The PRD, though, won only 10 percent of the vote, losing some 40 congressional seats. Its downfall reflects the strong showing of the Movement for National Regeneration, or MORENA, a new party split off from the PRD and led by former PRD presidential candidate Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador. MORENA gained about 8.5 percent of the vote, a significant showing for its first time out. It snatched the majority in the Mexico City Assembly and at least five of the city’s 16 boroughs from its progenitor.

Notably, the victory of independent gubernatorial candidate Jaime Rodriguez in the border state of Nuevo Leon is a slap in the face to all of the political parties, especially the PRI. Rodriguez developed his career in the PRI and served as mayor of Garcia, where he gained international attention for confronting organized crime. He harvested the discontent of the people with the party system and of PRI members disgruntled about the party’s internal selection process. Nuevo Leon’s major city is Monterrey, the industrial center of the nation, making it a very significant win for an independent candidate.

Persistence of Illegal Electoral Practices

Mexico’s elections were exceedingly expensive, costing some 8 billion pesos. That, however, did not save them from accusations of dirty tricks. The recently renamed National Electoral Institute, or INE, proved once again that it’s very efficient at absorbing public funds, but not so much at guaranteeing fair elections.

The PRI-allied Green Party, for example, ran a propaganda campaign that saturated Mexico’s media and public spaces beginning well before the designated campaign period and intensifying in the weeks before elections. The INE ordered a fine of 11.4 million pesos for disguising party propaganda as public affairs announcements, but later slashed the amount to a painless 1 million. The party was also fined 70,000 pesos for handing out food baskets in the state of Quintana Roo.

The Electoral Institute levied a total of 517 million pesos in fines against the party for multiple violations of election laws, sparking a citizen movement to rescind its registration. The INE criticized the Green Party’s blatant violation of the principle of fairness, but the damage was done. The party reported a huge leap in its electoral cache, guaranteeing the PRI coalition a ruling majority in Congress.

In another glaring problem, when the INE released its results of the vote count, it reported 100.61 percent of districts. In one district with 500 polling places, 550 were reported counted. While the INE blamed a “computer glitch,” opposition parties railed at its loss of credibility, which was low to begin with. It’s currently carrying out recounts involving 60 percent of the national vote.

Social networks, meanwhile, have been full of citizen reports of vote buying, coercion of public employees with threats of firing, and militarization at the polls. Sadly, much of this hasn’t been adequately documented or sanctioned, much less prevented. Though electoral laws and regulations have undoubtedly improved over the years, the INE seems to have little ability, and little desire, to make enforcing them common practice.

Institutional Violence

The government patted itself on the back for an election day “free of incidents.” The loved ones of Antonio Vivar would reject this evaluation.

According to witnesses, Vivar was shot and killed by government security forces in Tlapa, Guerrero in the midst of election-day conflict. There, the government raided the office of a protesting teachers’ union and then occupied the town with tear gas and full riot gear. Vivar was murdered in the offensive, and many others were injured.

In fact, some analysts have said these elections were the most violent since 2008.

Human rights organizations protested the high level of armed military and police presence at the polls. In the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Michoacan, and Chiapas, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center reported that “an alarming number of state and federal security forces were deployed, as well as soldiers.” It called the deployments and others incidents “a clear signal of authoritarian regression.”

Lower-intensity conflict characterizes the country from coast to coast, and from one troubled border to the other. Clashes and protests formed the backdrop for the elections and will be the foreground for the shaky governing forces that, by all indications, will continue to publicly boast of stability while employing force to put down rising protest.

The one immeasurable factor in these elections was the participation of organized crime. The shadow posers remained in the shadows, with numerous reports surfacing of places where they assigned candidacies, murdered unwanted candidates, and manipulated the vote.

Deep Discontent

So about half of eligible Mexicans turned out to vote, and the PRI kept its majority. Does that mean ordinary voters have confidence in the electoral system, the parties, and the politicians?

No. Mexico’s savvy populace is skeptical but wants to express itself. That’s good for a democracy.

What’s clear is that people will not limit their expressions to the voting box — a fact made clear by an active boycott-the-vote movement leading up to the election. The nation is still far from a U.S.-style system, where maintaining democracy is defined as going to the polls when elections are held. In Mexico, citizens are actively striving all year round for a democracy that seems to be receding.

Corruption will continue to be a big factor in driving popular anger. As we’re seeing in Honduras and Guatemala, Mexican politicians may also have to face the music in the near future. Mexicans have gone to the ballot box, but they’ll also turn up in the streets. Expect the barometer to rise.

Foreign Policy In Focus columnist Laura Carlsen directs the Americas Program for the Center for International Policy in Mexico City.

Source URL

|

Print This Print This

|

If you appreciated this article, please consider making a donation to Axis of Logic.

We do not use commercial advertising or corporate funding. We depend solely upon you,

the reader, to continue providing quality news and opinion on world affairs. Donate here

|

|

World News

|