|

|

CIA sought to sabotage Canada - Unable to think about two things at once, the Cuban Missile Crisis distracted them

Print This Print This

By Victor Ferreira | National Post

National Post

Thursday, Jan 4, 2018

Castro cronies in Toronto, JFK vs. Diefenbaker and paper companies: Why CIA plotted to sabotage Canada

CIA documents show at least one alleged Castro loyalist came to Toronto in 1958 to buy 10 surplus fighter jets

Only one month before the Cuban Missile Crisis brought 12 days of fear upon the world, eight high-ranking U.S. intelligence officials gathered at an undisclosed location to plot their next steps in removing Fidel Castro from power.

When these people met on Sept. 14, 1962, the U.S. still had no idea that Russian missiles were stockpiled in Cuba. Operation Mongoose, in which officials schemed to assassinate, discredit or trigger an uprising against the Cuban communist leader, still dominated these meetings. But on this day, General Edward Lansdale, the head of Mongoose, and General Marshall Carter, deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency, didn’t pitch National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy on exploding cigars and conch shells.

Instead, they focused on Canada.

|

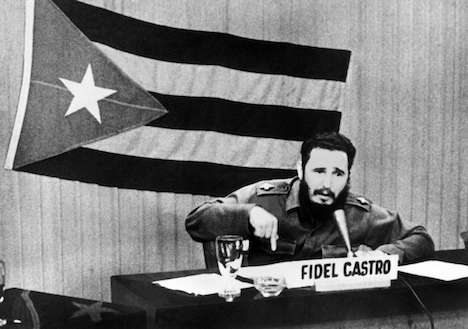

| The CIA planned to assassinate Fidel Castro, pictured on October 22, 1962, with the help of the Mob. AFP/GettyImages |

“General Carter said that CIA would examine the possibilities of sabotaging airplane parts which are scheduled to be shipped from Canada to Cuba,” reads a now declassified memorandum about the meeting.

Since July, the U.S. National Archives and President Donald Trump have released more than 25,000 secret files relating to John F. Kennedy‘s time as president and his assassination. The memorandum from the 1962 meeting reveals for the first time that the CIA was floating the idea of taking action against Canada.

|

| General Marshall Carter suggested sabotaging a Canadian shipment of airplane parts to Cuba during a secret meeting in 1962. WikiCommons |

No approval was given at this meeting, where Carter also asked Bundy to increase intelligence on Canada because of its “reporting funding of subversive elements in Ecuador and possibly elsewhere,” according to the memorandum. Bundy made it abundantly clear that “sensitive” ideas involving sabotage would have to be presented in more detail and decided case-by-case.

“This would have constituted a violation of Canadian sovereignty, but that shouldn’t surprise anyone,” said Arne Kislenko, a Ryerson university professor who teaches the history of espionage and once handled national security matters as a Canada Immigration officer for 12 years. “This is an agency which has undermined numerous countries.”

While it’s still unknown how the group reacted to CIA deputy director Carter’s idea, other sparse mentions of Canada in the JFK archives reveal that the CIA constantly kept one eye on Canada’s relationship with Cuba. And with good reason after it learned that an alleged Castro crony was operating in Toronto’s underbelly.

The sabotage mooted in the declassified memo, Kislenko said, could include anything from substituting the spare airplane parts for faulty ones to starting a fire at the factory where they were made. Canada’s relationship with the U.S. was tense leading up to the missile crisis, but it was unlikely the CIA would have risked an operation on Canadian soil when “it’s just so much easier to have a ship blown up at sea,” Kislenko said.

|

| President John F. Kennedy and Special Assistant to the President for National Security, McGeorge Bundy (right), look at a document as they walk along a north visitors’ entrance following President Kennedy’s meeting with President of Panama, Roberto F. Chiari on June 12 1962. Abbie Rowe. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston |

“Obviously the Americans were sufficiently pissed off and, logically following from that, if they didn’t resolve the matter through other means – diplomatic and friendly persuasion – then you always reserve the right to blow shit up.”

The U.S. was already involved in a cold war with the Soviet Union, but much of the tension between it and Canada was fuelled by another between Prime Minister John Diefenbaker and Kennedy.

Between 1960 and 1963, Diefenbaker defied the U.S. government in a display of stubborn nationalism. When Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower ordered a trade embargo on Cuba in 1960, Diefenbaker refused. Canada and Mexico became the only two countries in the western hemisphere to ignore the embargo. Diefenbaker believed that the Castro-led revolution that overthrew Fulgencio Batista deserved a chance to succeed. It also helped that he saw an opportunity to make a few dollars.

|

| John Diefenbaker and John F. Kennedy meet at the Oval Office on Feb. 20, 1961 University of Saskatchewan, University Archives & Special Collections, J.G.D. Diefenbaker fonds |

Cuba couldn’t rely on the U.S. for trade, so Diefenbaker cleverly planned to make Canada the middle man and profit as a trading partner. Canada would export everything from spare airplane parts to rail cars to Cuba, explained John Kirk, a professor of Latin American studies at Dalhousie University.

When Kennedy reached the Oval Office, the isolation of Cuba heightened. Of course, he expected Diefenbaker to follow in lockstep, not only on Cuba but on foreign policy and nuclear armament. So when the grizzled prime minister shut down the playboy president, Kennedy fumed.

|

| A rare photo of John F. Kennedy as John Diefenbaker smiling during the U.S. president’s visit to Ottawa on May 16, 1961. University of Saskatchewan, University Archives & Special Collections, J.G.D. Diefenbaker fonds

|

“(Kennedy) hated Canadian nationalism and thought Canada was the boonies,” Kirk said. “He had a tremendous imperial arrogance towards Canada.”

The hatred was more than mutual.

Kennedy visited Ottawa in May 1961 for a series of meetings with Diefenbaker on foreign policy. After their final meeting, Kennedy returned to Washington but mistakenly left something behind. It was a memo titled: “What We Want from the Ottawa Trip.” The document listed four foreign policy areas that Kennedy would “push” Diefenbaker on.

|

| John Diefenbaker introduces John F. Kennedy to the House of Commons on May 17, 1961. Kennedy would publicly ask for Canada to adopt the U.S. foreign policy in his address, leaving Diefenbaker fuming. |

When an assistant found the memo and handed it to Diefenbaker, he refused to send it back to the U.S. and instead read it again and again, becoming more livid with each reading and underlining the word “push” twice in blue ink. Kennedy was a bully, Diefenbaker thought, and he’d get nothing from Canada.

The memo would surface again during the 1962 Canadian election when Kennedy was clearly supporting Diefenbaker’s opponent, Liberal opposition leader Lester B. Pearson. In a fit of rage brought on by finding Kennedy invited Pearson instead of him to a Nobel Prize gala, Diefenbaker pounded his desk, produced the memo and threatened to make it public. He had to show the Canadian public that he was the only one who could stand up to the Yankee bully. When news of the threat reached Bundy and Kennedy at the White House, the first solution the president offered was to “cut his balls off,” before calling Diefenbaker a “prick,” a “fucker” and his most common phrase for Diefenbaker: “That son of a bitch.”

“Just let him try it,” Kennedy shouted at the meeting, ending it by threatening to never speak to Diefenbaker again.

|

| President John F. Kennedy invited Lester Pearson instead of John Diefenbaker to the Nobel Prize Gala at the White House on April 29, 1962. The photo of them smiling together while chatting with author Pearl Buck ran in newspapers across the country. AP Photo/Byron Rollins |

Six months later, on Oct. 14, 1962, the Americans learned that the Soviet Union was storing missiles in Cuba. This lead to more than a week of threats between the U.S., Cuba and the Soviet Union that brought the world to the brink of thermonuclear war. Americans lived in constant fear, listening to their radios for breaking news and waiting to hear civil defense sirens blare in the streets. Children practiced quickly hiding under their desks at school.

Fuelled by his hatred of Kennedy, Diefenbaker refused to put the Canadian military on high alert and only acted when the crisis was over. It was actions such as these that led to his defeat by the Kennedy friendly Pearson in the 1963 election.

During Diefenbaker’s term, Canada never made the headway the prime minister expected on trade with Cuba, Kirk said. Part of that arose from the U.S. warning Canadian corporations to “think twice” about trading with Cuba if they still wanted business.

With Pearson still two months from office, the CIA finally determined that Canada’s trade with Cuba was not a matter that would lead to conflict, according to a declassified Feb. 23 1963 report. Sure, the CIA showed its hatred of Diefenbaker, who “wishes to exploit the anti-American line,” but it concluded the Canadian diplomatic missions in Cuba were too valuable to compromise.

So sabotage was out. But why was it even considered in the first place?

One day before the CIA made its conclusion on Canada, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara privately updated the Senate on Cuba in a meeting revealed by another set of declassified documents.

Senate chairman Richard Russell Jr. asked McNamara whether there had been any success in eliminating Cuban trade with Mexico and “our good friends Canada”.

McNamara, known for later leading the U.S. into the Vietnam War, had one concern — and it was about the spare parts shipments. They were a problem because he believed that dummy corporations were the ones shipping them to Cuba.

|

| U.S. President John F. Kennedy meets with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in the White House’s Cabinet Room. ecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston |

“I think there was evidence that fictitious corporations were being used as facades behind which the parts that were of value to Cuba were being shipped into Cuba,” he said.

Cuba was cleverly skirting the U.S. embargo, having secured several American-made items from Panama during this period. According to Kislenko, the espionage historian, if Cuban supporters were working in Canada, they would have needed aliases and would have had to ship out products using false tags to cover their tracks.

McNamara gave no evidence to support this but according to another set of CIA documents, there was at least one alleged Castro loyalist who came to Toronto on his behalf.

Nothing except what was revealed in the CIA documents is known about Louis Martinez, a man who worked as an attorney in the U.S.

|

| John F. Kennedy and Robert McNamara walk through the halls of the Pentagon on May 29, 1962. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston |

Martinez’s former girlfriend, Viola Krajcik, served as a CIA informant after the agency suspected him of being involved in the robbery of more 300 weapons from a national armoury in Ohio in 1958. Krajcik made it clear that Martinez was working on behalf of Castro and the Cuban rebels — who hadn’t yet defeated Batista — to secure weapons and medicine.

In either July or September 1958, Martinez brought Krajcik with him to Toronto for the purpose of buying 10 surplus fighter jets for Castro.

The pair stayed at the Conroy Hotel, a two-storey building at Dufferin St. and Lawrence Ave. once known as a New Years Eve hotspot for couples. Krajcik said they travelled to the municipal airport to see planes that were only described as silver. But the Panamanian pilots who were hired to fly the planes out of Canada were not allowed into the country, the CIA wrote. The deal still went down and without telling the CIA how, she said the planes were stashed in New Jersey.

The man who helped the deal go through, Krajcik said, went by “Vic.” Vic was 5’3, 60 years old and owned an expensive home in Milwaukee. He told her that he once lived in Canada and had served as a pilot in the Canadian Air Force. Now, he appeared to be working as an industrialist of some sort in the U.S.

|

| Louis Martinez stayed at the Conroy Hotel in Toronto in 1958, according to CIA files. City of Toronto Archives |

Before Martinez was eventually arrested in New York for kidnapping, Krajcik said her former lover was given $30,000 for an arms deal that never went through. He also allegedly tried to buy rifles in Brooklyn, N.Y. for Castro. At one point, Martinez flew to Cuba where he said he was thinking of taking $10 million from Castro to construct a Pan American building in Miami. When he was arrested, Martinez denied all involvement with the Cuban rebels. No other information about his alleged ties to the rebels is known.

Even though the CIA no longer saw Canada as being in a position of conflict, new documents show that Kennedy’s inner circle was still not pleased. During a Nov. 12, 1963 meeting, CIA officer Desmond Fitzgerald briefed Kennedy on Canada and said it was still “refusing to cooperate” in the “economic denial” of Cuba. He called on Kennedy to strengthen the program to deal with Canada’s “most serious” behaviour. An undated CIA document shows that the CIA was pushing for sanctions against Canada.

It’s likely Canada had no idea of the CIA plans when Pearson agreed to allow Canadian diplomats in Cuba to spy on the Soviet Union on behalf of the U.S. intelligence agency.

|

| John W. Graham’s memoir Whose Man in Havana revealed he spied on the Soviet Union in Cuba. Julie Oliver/Ottawa Citizen |

John W. Graham served as a Canadian diplomat in Cuba almost immediately after the Cuban Missile Crisis between 1962 and 1964. Disguised as a Soviet soldier, Graham entered their military bases to keep track of their weapons, machinery and troop numbers and regularly report back to Ottawa using a cipher machine.

Along with Canadian diplomats turned spies, the CIA hired other Canadians — without the government’s knowledge — to do their bidding in Cuba. Canadian pilot Ron Lippert was hired by the agency to smuggle explosives packed in papaya into Cuba. Graham visited Lippert in prison after the pilot was caught.

Despite being privy to secret information, Graham had no knowledge about the CIA keeping tabs on Canada. It’s standard intelligence practice, Kislenko said, to spy on your allies like your enemies.

|

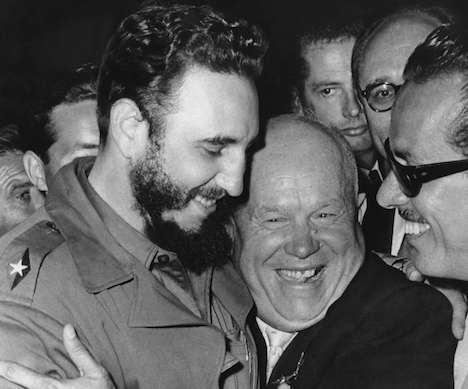

| In a Sept. 20, 1960 file photo, Cuban leader Fidel Castro, left, and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev hug at the United Nations. AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler, File |

But even if Graham had known, it wouldn’t have changed his willingness to spy on the Soviet Union. His work, Graham said, helped the CIA understand that the Soviet Union was keeping its end of the bargain and no longer stashing intercontinental missiles on Cuba.

“There was a risk of thermonuclear war,” Graham said. “The more I was able to go to a Cuban military camp, prowl around the exterior and look at … their equipment and describe that and sketch that, the more the American intelligence community realized (Soviet Union leader Nikita) Khrushchev was keeping his word.”

Source URL

|

Print This Print This

|

If you appreciated this article, please consider making a donation to Axis of Logic.

We do not use commercial advertising or corporate funding. We depend solely upon you,

the reader, to continue providing quality news and opinion on world affairs. Donate here

|

|

World News

|