Truthdig editor’s note: The past is prologue. The stories we tell about ourselves and our forebears inform the sort of country we think we are and help determine public policy. As our current president promises to “Make America great again,” this moment is an appropriate time to reconsider our past, look back at various eras of United States history and re-evaluate America’s origins. When, exactly, were we “great”?

Below is the eleventh installment of the “American History for Truthdiggers” series, a pull-no-punches appraisal of our shared, if flawed, past.

***

“The ‘revolution of 1800’ … was as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of [17]76 was in its form; not effected indeed by the sword, as that, but by the rational and peaceable instrument of reform, the suffrage of the people.”

—Thomas Jefferson in an 1819 letter

to Judge Spencer Roane

We tend today, in our hyperpartisan moment, to imagine that politics have never been worse, more tribal, more contentious than they are now. But is that true? The United States was born of revolution, fought a bloody civil war and has changed time and again throughout its history. And, in 1800, the nascent republic would experience its first-ever electoral transition to a president of the opposing party. That election and its aftermath would have profound implications for the young republic and ensure some degree of Jeffersonian legacy for generations to come. Jefferson’s words—the output of his pen—were often beautiful, but some darkness lurked beneath the surface of his self-proclaimed republican, agrarian utopia.

The Revolution of 1800?: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and the Partisan Rancor of an Election

The insults, untruths and outright verbal attacks during the 2016 election season shocked the American conscience and rattled the republic. Still, even the worst of the exchanges between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump hardly compare with the pejorative language slung in both directions by supporters of rivals John Adams (the sitting president, seeking re-election) and Thomas Jefferson (the sitting vice president, seeking the presidency) in the election of 1800.

Jeffersonian newspapermen called President Adams and the Federalists “loyalists,” “monarchists,” “Tories” and the “British faction.” Essentially, so the thinking went, these Federalists, led by Adams, were traitors, and loyal Republicans needed to “turn out [to vote] and save [their] country from ruin!”

Of course, the fierce rhetoric ran both ways. One Federalist paper predicted that, should Vice President Jefferson be elected president, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, and the soil will be soaked with blood.” With the ad hominem attacks running at that fever pitch, it is little wonder that the country seemed to be on the verge of civil war after the election results were so close that the matter had to be sent to the Congress for adjudication. Rumors and conspiracies flourished, and many armed themselves for the expected chaos.

|

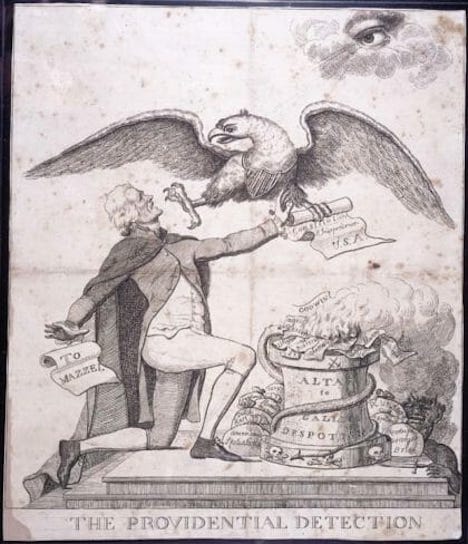

| In this political cartoon, an eagle prevents Jefferson from burning the Constitution. (American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.) |

It never came. After dozens of tied votes in the House between Jefferson and his preferred vice president, Aaron Burr, a number of Federalists relented and handed victory to Jefferson. In the convoluted system of the day, presidential electors in the Electoral College did not designate which of the two men running on a given ticket (Federalist or Republican) was preferred as president and which as vice president. Therefore, when Jefferson bested Adams in a rather close election, both he and his running mate, Burr, had the same electoral vote count. Loathing Jefferson deeply, some Federalists threatened to throw their support behind Burr, but, after dozens of tied votes, a few Federalists—ironically under the direction of Jefferson’s sworn enemy, Alexander Hamilton—gave in and ensured Jefferson’s election.

Did this constitute a revolution? It is hard to say. Certainly Jefferson thought so, and indeed the governing theories of the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans were almost diametrically opposed. The two parties even celebrated different holidays marking the birth of the nation, with the Republicans focused on the more egalitarian celebration of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence (July 4th), while the Federalists favored a celebration of Washington’s birthday. This was, truly, a country divided.

What is certain is that the United States had (just barely) survived its first peaceful transfer of elected power from an incumbent president to an opposition successor. Think of all the recent European, African and Asian countries that have struggled so mightily, and often failed, to pass that vital democratic test.

|

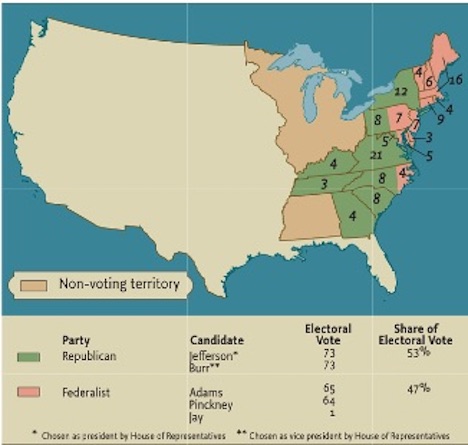

| The Electoral College map of 1800. |

Still, there remained something disturbing about the 1800 (and 1796) election map. The nation was clearly dividing into opposing sections. Nearly the entire South voted Republican, and absolutely all of New England went Federalist. The division was about more than the peculiar institution of slavery—though that played a part—and came down to conflicting worldviews of what republican, post-revolutionary society should be. For the Jeffersonians, the future was agrarian, expansive, ultimately dominated by the “people,” the yeomanry. Its future lay westward. The Federalists were often commercial elites, with proprietary wealth and aristocratic ambitions. They looked to the east, to the sea and to Europe for the country’s future.

It is all so bizarre in hindsight: Jefferson—a textbook planter aristocrat with some 200 slaves—sought to represent small farmers in the South and what was then considered the West, and middling artisans in the North. Adams, though a successful lawyer and proponent of powerful federal governance, owned no slaves and lacked the plantation lifestyle of Jefferson the gentlemen.

Republican Reforms: The Jeffersonian ‘Utopia’

“But every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

—Jefferson’s first inaugural address,

March 4, 1801

“There are no red states or blue states, just the United States. … [T]here is not a liberal and a conservative America—there is only the United States of America.”

—Sen. Barack Obama, speaking

at the Democratic National Convention in 2004

Ultimately, Jefferson, the wealthy planter who claimed to speak for the lowliest laborer, emerged victorious in the presidential election of 1800. Knowing how close the nation had come to civil strife, Jefferson, not half the public speaker that he was a writer, used his inaugural address as a call for unity. Not everyone bought it. Jefferson’s two terms were highly partisan, antagonistic and controversial. The Federalists could hardly stomach the man; most Republicans worshipped him. Sound familiar?

Nevertheless, whether or not his victory constituted a “revolution,” Jefferson’s America underwent profound changes, democratizing certain aspects of society and of the civic culture. Staying true, initially, to his principles, Jefferson began slashing federal spending and federal departments. Hamilton’s old Department of the Treasury was eviscerated. Jeffersonians believed in a small, unobtrusive government and sought to create one.

An early target for the Jeffersonians was the Federalist-dominated Army. Defense spending was cut, troop numbers decreased, and—somewhat counterintuitively—a new federal military academy, at West Point, was begun in 1802. But a closer look indicates that even this had political motivations. West Point was to be a training ground for Republican-inclined officers, an antidote to the many Federalist officers in the ranks.

Political changes translated to social changes as (at least white male) society democratized. In referring to those higher on the socioeconomic ladder, workers and servants ditched the titles “master” and “mistress” for “Mr.” and “Mrs.” and the more colloquial and less deferential Dutch term of “boss” often served as a substitute for “master” as well. Indeed, if, as Jefferson famously wrote, “all men were created equal,” then why adhere to any hierarchy at all? The Federalists were aghast at the comeuppance of these unfettered masses and pined, ironically, for a pre-revolutionary society.

|

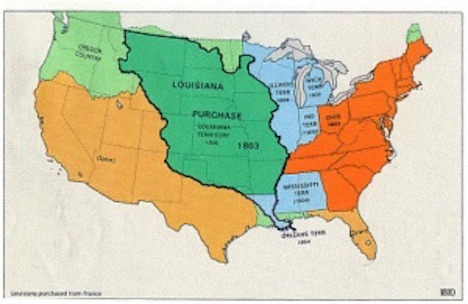

| The Louisiana Purchase. |

‘Empire of Liberty’: Jefferson and the West

“We shall … add to the empire of liberty an extensive and fertile country.”

—Thomas Jefferson in a letter

to George Rogers Clark in 1780

“I infer that the less we say about the constitutional difficulties respecting Louisiana the better, and what is necessary for surmounting them must be done.”

—Jefferson to James Madison (1803)

Suffice to say, it wasn’t exactly “street legal”—the famous Louisiana Purchase, that is. Could it really be constitutional for federal agents, appointed by the government, to purchase an immense tract of land and double the size of the country without explicit authorization from the president or Congress? The envoys were supposed to buy only New Orleans and ended up paying a bargain price for a vast continent. One would think the small-government, constitutionally constructivist Republicans would be appalled at such an expansion of federal power. And yet, Jefferson and many of his followers thought it vital and in America’s interest.

It’s ironic, really. After all, vast new territories inevitably meant a groundswell of government officials: surveyors, marshals and soldiers to garrison the frontier, Indian agents to negotiate treaties, and so on. Still, Jefferson saw the expansion of his famed “empire of liberty” as both pragmatic and idealistic. Pragmatic because the new nation had a small Army and feared the presence of French and Spanish lands to the south and west and British power to the north. Acquiring Louisiana would make America a continental power once and for all and keep Napoleon’s France from threatening the young republic.

Still, Jefferson was motivated by so much more than that. He always looked westward, was veritably obsessed with the West all his life (though he never traveled there). He was awestruck by native peoples but contributed greatly to their eventual expulsion and destruction. The Louisiana Purchase, after all, spelled disaster to the then-independent Native American nations that actually lived there. Still, Jefferson thought the extension of republican modernity would lift Indian living standards and turn Native Americans into modern, democratic farmers.

That was the point, Jefferson believed. The United States must not look to the sea or to Europe when modeling society. Europe, the Old World, remained monarchical and hierarchical to the core. For the American republic to blossom, it must remain a nation of small, independent farmers. Land ownership and self-sufficiency made for the best republican citizens. By this logic, and given the exploding America’s population, expansion was not only desirable but necessary—an existential matter, indeed.

To the end of his life, Jefferson seems to have believed he could organize and rationalize the settlement of the New West and thereby “save” Native Americans. Ultimately, however, the slipshod tide of settlement inundated the tiny federal bureaucracy, leading to squatting, overdevelopment and the stealing of native lands. Violence begot violence, and the outnumbered Indians were overwhelmed. Jefferson, perhaps the most expansion-minded president in American history, summed up the triumph thusly: “[N]o constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire [emphasis mine] and self-government.” Of course, he meant an empire and self-government for white Americans. The natives hardly stood a chance.

American Sphinx: The Unknowable Character of Thomas Jefferson

“[Jefferson], the philosophical visionary, may be ideally suited to be a college professor, but is not suited to be the leader of a great nation.”

—Alexander Hamilton in an 1802

letter to Rufus King

Jefferson’s idealism regarding Indian policy was just one of many contradictions at the heart of his life and political philosophy. So much has been written about this fascinating, ingenious and deeply flawed Founder that he almost appears unknowable.

The native enthusiast who opened western land and the path to Indian expulsion. The opponent of federal power who agreed to keep the National Bank, waged a naval war with Barbary pirates, and nearly shut down the American economy through the severe restrictions of his Embargo Act (meant to gain leverage over the feuding British and French by cutting all trade with both). The lifelong critic of standing armies who funded a national military academy.

Furthermore, he was an opponent of slavery (at least in certain writings) who himself owned more than 200 human beings. The man obsessed with the supposed evils of racial mixing who himself fathered several children with his slave, Sally Hemmings. That story, more than all the others, may best personify the complexity of Jefferson the man.

Jefferson’s wife, Martha, died at age 33 after suffering difficult childbirths and several months after the birth of her last child. Jefferson, who was heartbroken, was 39 at the time. From his wife he inherited many slaves. One, the teenage Sally Hemmings, was one-fourth black and—because she was the child of Martha’s father—was Martha’s half sister. (It was common for slave owners, through rape, to impregnate women they owned.) According to some reports, Sally and Martha, sharing a father, looked alike. Jefferson would eventually father a number of children with Hemmings. These children, one-eighth black, remained enslaved on Jefferson’s plantation to the end of his life, often working in the house. Visitors to Monticello were known to remark on the resemblance of some of Jefferson’s slaves to their master.

|

| A circa-1804 caricature showing Jefferson as a rooster and Sally Hemmings as a hen. |

This was the family of Jefferson, of the man who penned “all men are created equal” and clamored about the evils of racial mixing. Though rumors of Jefferson’s miscegenation were common even at the time (see the cartoon above), most historians refused to believe the Hemmings story until in recent decades it was incontrovertibly proved, in large part through DNA testing. It seems that generations of historians, enamored by this Founding Father, second in esteem only to George Washington, could not bring themselves to accept his hypocrisies.

We’ll never know for sure, but I tend to believe that Jefferson loved Sally, that her resemblance to his dead wife comforted a grieving and lonely man. This does not excuse Jefferson’s blatant hypocrisy but does, I think, illustrate the complexity of humans, then and now.

Between Freedom and Slavery: Jefferson, Free Blacks and Republican Slaves

“The rights of human nature [are] deeply wounded by this infamous practice [of importing slaves] and the abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state.”

—Thomas Jefferson (1774)

Jefferson was not alone in walking a tense and fine line between freedom and slavery. Indeed, the entire republic toed that line throughout the Jeffersonian era and until the Civil War. Society, especially in the North, was democratizing. Larger and larger segments of the population could vote, and they called for more rights and less social deference. In the post-revolutionary period of idealism and excitement, many—North and South—began to predict the coming end of slavery. They were horribly mistaken.

In fact, Southern plantation chattel slavery was about to enter its golden era. Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin meant that the demand for this new cash crop would explode, requiring more hands to pick and carry the valuable crop. Slavery also expanded into the new southwest territories gained in the Louisiana Purchase. Furthermore, fear—visceral white fear—drove planters to tighten the proverbial leash and institute a slave culture even more reliant on terror.

In the 1790s and 1800s, another New World possession, a former colony, became just the second country to gain its independence from colonial masters. One would imagine the United States would be thrilled to embrace this kindred spirit of a nation. But this was a black country: Haiti. The Haitian slaves and free blacks waged a brutal war of independence with France for more than a decade. There was slaughter on both sides, and many white planters were murdered or became refugees. This newly independent black republic was the absolute talk of the town, and news of its brutality spread widely.

The very existence, and example, of the Haitian overthrow of the French terrified Southern planters in the United States. They knew, though it is remarkable to imagine, that even their own slaves had heard talk of the black victory in Haiti. Thus, when a Virginia slave named Gabriel plotted a similar (though smaller) uprising in 1800, the uncovered conspirators were dealt with harshly: Dozens were hanged. Jefferson’s American republic, in fact, so feared the Haitian rebels that the U.S. would not recognize the independence of this sister republic in the Western Hemisphere until the American Civil War.

Still, due to manumission, grants and purchases of freedom, and free black immigration, a class of independent African-Americans began to grow—especially in the North. Ironically, the presence of these free, sometimes educated, blacks caused unease among Northern and Southern whites. Fears sparked by the role of free blacks in the Haitian Revolution, and by Gabriel’s conspiracy, led Northern and Southern states alike to actually move backward and further restrict the rights of free blacks. Northern states developed segregated communities, took away or banned blacks’ rights to vote, and otherwise restricted their freedom. Southern states passed “black codes” similar to those of the later Jim Crow era and eventually expelled most or all free blacks to the north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Consider the irony: Jeffersonian America, while a substantially democratizing white, male society, actually restricted the freedom of free blacks and hardened the institution of slavery (even though slavery was gradually ending in the Northern states) into its most brutal manifestation in American history. As such, a free black man in New York or Boston tended to have more rights in 1790 than in 1808—at the end of Jefferson’s second term.

* * *

As with Jefferson the man, so it was with Jeffersonian America writ large. A mess, a mass of contradictions; a darkness lurking beneath and tottering the nation’s very foundations. Already Northern and Southern society was diverging. Already the contradictions of liberty for some (white men) and slavery or destruction for others (blacks and natives) were shaking the nation.

It was the burden of our American society to bear this inconvenient and uncomfortable fact: that our most ardently democratic Founder, with a pen of gold and ideas so beautiful they can move one to tears, was also a slave owner and signed the death warrant of many thousands of Indians and that of an entire way of life.

Still, Jefferson—for all his flaws—remains forever bound up in the fabric of America’s past and also of its present. His democratizing instincts, agrarian glamorizing and distrust of federal power are alive still in the American psyche and within the platforms of modern political parties.

Shall America be “great again”? Was it ever? Or, indeed, does the Jeffersonian revolution demonstrate the precarious foundations of a flawed and ever changing society?

Jefferson’s contradictions are America’s too. Then, and now.

* * *

To learn more about this topic, consider the following scholarly works:

- James West Davidson, Brian DeLay, Christine Leigh Heyrman, Mark H. Lytle and Michael B. Stoff, “Experience History: Interpreting America’s Past,” Chapter 9: “The Early Republic, 1789-1824” (2011).

- John M. Murrin, “The Jeffersonian Triumph and American Exceptionalism,” Journal of the Early Republic 20, Number 1 (Spring 2000).

- Peter S. Onuf, “The Revolution of 1803,” The Wilson Quarterly 27, Number 1 (Winter 2003).

- Gordon Wood, “Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815” (2009).

Source URL

|