Once a white supremacist, always a white supremacist?

Print This Print This

By Nick Purdon and Leonardo Palleja | The National

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

Friday, May 10, 2019

|

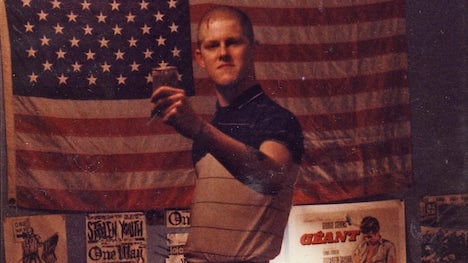

| Arno Michaelis has taken a vocal stand against racism, but as a young man growing up in Milwaukee he was a white supremacist. 'In the movement I was a big deal,' he says. 'I was the lead singer of Centurion. I was one of the first Hammerskins, I was reverend in racial holy war. People seemed to respect me or were afraid of me.' |

They never repaired the bullet hole.

On Aug. 5, 2012, a white-supremacist gunman stormed into the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin and opened fire.

Satwant Singh Kaleka, the president and revered leader of the gurdwara in Milwaukee, took five bullets in his torso when he confronted the shooter and tried to stop him.

"My father died a heroic death. He died fighting against a racist gunman," says his son Pardeep Singh Kaleka.

"He died in the place that he helped build. He might have lost that fight, but we continue on in that battle."

After the shooting, Milwaukee's Sikh community decided not to fix the damage done to the doorframe by one of the gunman's bullets.

Instead, they installed a small plaque below it that reads: "We are one."

"I think there is a beauty to our painful history," Kaleka says. "We are going to be resilient through all of this. 'We are one' are also the first words in our scripture."

|

| A small plaque below the bullet hole left in a doorframe by a gunman's attack on the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in Milwaukee reads, 'We are one.' (Nick Purdon/CBC) |

Searching for answers

In the days after the shooting, Kaleka says he did all the things he imagined his father would have done.

He helped members of the congregation with their funeral arrangements. He became a spokesperson for his community.

But above all, he tried to make sense of the events of that day. Six people were killed and four wounded before the shooter turned the gun on himself.

|

| Pardeep Singh Kaleka's father, seen in the photo on the wall behind him, was murdered by a white-supremacist gunman. (Nick Purdon/CBC) |

"We weren't surprised that a white supremacist would do something like this," Kaleka says. "It just hurt because people were trying so hard to become part of the American fabric, and to be told that you are not American enough — hurts.

"I wanted to know why the shooter did what he did," Kaleka adds. "Why did he come to that temple on that day, on that morning, and kill the people that he did?"

Arno Michaelis, white supremacist

What Kaleka didn't know was that someone else in Milwaukee at that time was also desperate to find out more about the killer.

On the evening of the attack, when it was announced that the shooter was a white supremacist, Arno Michaelis was ashamed and worried.

Michaelis had been a leader in the white power movement in Milwaukee.

"In so many ways this guy was exactly who I used to be," he says.

|

| For seven years as a young man, Arno Michaelis lived and breathed violence. 'When you practice hate and violence,' he says 'things like love and kindness and compassion and forgiveness, all the aspects of being a human being, are not only foreign to you - they are repulsive to you.' |

For seven years as a young man, Arno Michaelis lived and breathed violence. 'When you practice hate and violence,' he says 'things like love and kindness and compassion and forgiveness, all the aspects of being a human being, are not only foreign to you - they are repulsive to you.'

"I lay awake that night thinking [what] if it was someone that I recruited or someone that I knew from back in the day. I had this really sinking feeling from the get-go that I had something to do with this."

That's because for seven years, Michaelis had lived and breathed racism.

He was a founder and leader of a worldwide skinhead movement. He sang in a popular white power band.

It was music that got Michaelis involved in white supremacy when he was 16.

"The lyrics were about race and nation and blood and soil, and all these really seductive themes that Adolf Hitler used to corrupt the minds of so many Germans back in the '30s and '40s," he says.

"To me, all that language resounded with me. I didn't really care about anything up until then."

In those days as a young man, Michaelis says he radiated hostility. He explains how he was always trying to recruit people to his movement.

Michaelis doesn't shy away from admitting what he did. In fact, he says he wants people to know exactly what a white supremacist is capable of.

"I don't know how many times there were 10 of us walking down a street, and if we saw one lone guy and it was a just target of opportunity, we'd just jump on him and beat the mess out of him. Leave him a bloody pulp," Michaelis says.

"Sometimes it was because they were black, sometimes we thought they were gay, and we'd just jump on them and brutally beat them and leave them for dead."

Michaelis adds that his white power group had plenty of guns in those days, because they were preparing for a race war they believed was imminent. If he hadn't left the movement, Michaelis wonders if one day he might have gone into a place of worship and killed people.

"Had I continued down that path, it's certainly within the realm of possibility that the ideology would have made me so miserable that nothing but homicide followed by suicide seemed to make sense," he says.

Birth and re-birth

What Michaelis says saved him was the birth of his daughter.

"By that time I had lost count of how many friends had been incarcerated," he says. "And it finally hit me that if I don't change my ways, then death or prison is gonna take me from my daughter."

|

| In 1994 Michaelis found himself a single parent to his 18 month old daughter. (Michaelis family) |

Michaelis left the movement. He took a job as a computer programmer.

He believed he'd left the world of white supremacy behind.

But when the shooting happened at the Sikh temple, his past came back — the shooter was a member of the same racist group Michaelis helped start.

"I certainly felt a real urgent responsibility because of the actual hands-on role that I had in bringing that group to life," Michaelis says.

Once a white supremacist always a white supremacist?

Meanwhile, Pardeep Kaleka, still trying to understand his father's murder, did something that would change his life.

Searching for answers, he contacted Michaelis.

"I just thought he might know the shooter," says Kaleka. "And he might be able to get into the intricacies of the day or the day before, and why he chose that place.

"I was really just looking for an explanation."

Kaleka spoke to Michaelis a few times on the phone before they decided to meet at a nondescript Thai restaurant in downtown Milwaukee.

|

| Kaleka and Michaelis still eat regularly at the Milwaukee restaurant where they first met. 'A lot of people think 'oh they get together every once in a while and do a talk,'' Kaleka says. 'But we are genuine friends. My kids know him as uncle Arno. His daughter knows me as uncle Par. He is an amazing friend and an amazing brother.' (Nick Purdon/CBC) |

"There was a part of me that was like, 'what am I doing?" Kaleka says. "Because part of you thinks 'once a white supremacist always a white supremacist.'"

The two men sat down together. They made small talk, and then Kaleka asked Michaelis the question that had been eating at him.

"When I asked Arno 'why did the shooting happen,' he responded quite simply: 'hurt people hurt other people,'" says Kaleka.

"He was honest, saying he didn't know who the shooter was, but that the shooter was very much who he used to be," Kaleka adds.

An unlikely friendship

Against all odds, Kaleka and Michaelis formed an unlikely friendship.

"We talked a lot about our dads," Michaelis says. "And we talked a lot about our daughters. And we found out, as we are sharing stories, about how similar not only our loved ones were, but how similar we were."

They committed to working together to stop the racist violence that had brought them together.

|

| Today Kaleka and Michaelis run an organization called Serve2Unite, where they promote compassion and inclusion. (Nick Purdon/CBC) |

"People oftentimes ask me, 'Why did you do that?'" Kaleka says. "The main reason I did that was to understand why people do what they do — and the more important thing, what are we gonna do about it?"

"I knew right there that Pardeep was gonna be an important part of my life," Michaelis says.

Today Kaleka and Michaelis have created an organization called Serve2Unite that works with young people and educational institutions to cultivate compassion and inclusion.

They travel the world telling their story of how friendship overcame hate, and they meet hundreds of people — students, politicians — and push them to take action against racism.

"Dad's life was one of connection and it was one of love," Kaleka says.

"And I look at me and Arno's journey together as an extension of that love. The lasting message from what happened on Aug. 5 is NOT going to be the shooter's rampage."

Source URL

|

Print This Print This

|