|

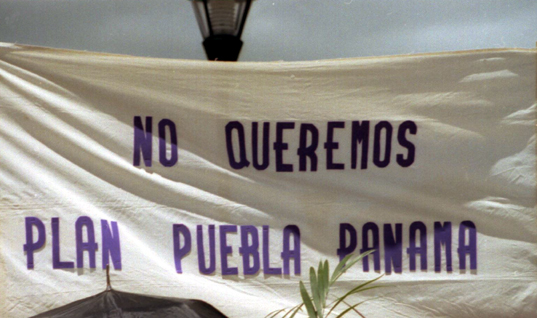

| "We Don't Want Plan Puebla Panama." (La Otra en Campeche) |

|

At the "IX

Tuxtla Summit," held July 24 in Costa Rica, the declaration against the

Honduran coup d'etat captured the headlines of regional newspapers. The

declaration nearly overshadowed the main purpose of the meeting, which

is the advancement of a regional integration plan previously known as

Plan Puebla-Panama (PPP).

The regional heads

of state, plus the Dominican Republic and Colombia, agreed to continue

with the integration plan that includes infrastructure mega-projects to

make the region more "competitive" within the framework of neoliberal

globalization, or the "Washington consensus." This framework has been

rejected by many experts and communities, given the global financial

crisis that it has provoked and the grave impacts of accelerated

inequality, the displacement of local communities, and environmental

destruction.

The PPP was

re-launched by President Felipe Calderon of Mexico in a meeting in

Campeche in April 2007. At the Tuxtla Summit in 2008, the PPP was

re-baptized the "Mesoamerican Integration and Development Project"

(MIDP). Promoters felt compelled to change the name due to widespread

local, national, and international resistance to the PPP. Grassroots

organizing managed to halt several projects and put a serious crimp in

the multimillion-dollar public relations efforts to promote the plan.

Leaders at this

summer's summit reviewed the 2008-2009 report on advances in the

Mesoamerican Integration and Development Project. The Project changes

very little of the original PPP, designed to facilitate foreign

investment and link the region to the needs of the U.S. economy.

Priority projects currently under the MIDP include the construction of

an Interconnected Electric System for Central America (SIEPAC) with a

transmission line running from Guatemala to Panama, the construction of

381 hydroelectric dams, a 10,209 km. network of highways throughout

Mesoamerica, agribusinesses, and the construction of biofuel plants.

According to the latest information available, the PPP-MIDP encompassed

99 projects with a cost of more than $8 billion.

The new version

adds a few social projects in education and health and creates a new

institutional framework. However, it does not modify the model of

integration/fragmentation that is oriented toward the international

market and the exploitation of natural resources by transnational

corporations.

The summit's

final "Declaration of Guanacaste" acknowledges the principle financers

and collaborators of the project: the Inter-American Development Bank,

BCIE, CAF, CEPAL, SG-SICA, and SIECA. It calls on the Executive

Commission of the PPP-MIDP "to increase its efforts to provide the MIDP

with management instruments, incorporating baselines and indicators

that facilitate tracking and monitoring activities and a work plan,"

"incorporate Finance and Treasury Ministers into the permanent

structures to reinforce the link between regional initiatives that the

project finances and the pertinent budgeted national programs," and

"implement the actions laid out in the report." The highlighted

priorities are the program "Acceleration of Pacific Corridor of the

International Network of Highways (RICAM), port projects, and

acquisition of transportation rights needed to finalize the SIEPAC

infrastructure within the timetable."

These projects

imply serious damage to the environment and the displacement of local

communities and small-scale farming and fishery activities. Although

the MIDP incorporates some mechanisms for consultation with affected

communities, they fall far short of respecting the necessary minimum

that is established in Article 169 of the ILO and other conventions.

Attack on Biodiversity

The PPP-MIDP

covers one of the largest areas of natural resources and biological and

cultural diversity on the planet. Referred to as the Mesoamerican

"hotspot," it contains 7% of the world's known species and around 5,000

endemic species. It is a region in danger—just 20% of its original

vegetation has been preserved.

One example

reveals the damage done by the regionally imposed integration model. A

study done by Strategic Conservation concludes that one section of the

RICAM that passes through the Mayan Jungle would incur the

deforestation of around 311,170 hectares of the jungle over the next 30

years. It would also fragment jaguar habitat into 16 pieces; increase

the vulnerability of the ecosystem to hurricanes and wild fires;

facilitate land invasions, illegal logging, and illegal flora and fauna

trade on the black market.

The study finds

very few benefits in the project for the local campesino and indigenous

populations while finding many possible damages to their traditional

economic activities. It undertakes a cost/benefit analysis taking into

account the cost of at least 225 million tons in carbon emissions with

the global environmental cost of at least $136 million (at the current

monetary value) and concludes that even the economic results are

negative:

"This study calls into question the implementation of a development

model, characterized by large infrastructure projects such as those

proposed by the Plan Puebla-Panama and the Mundo Maya Project, within

the Mayan Jungle. In some cases, these models demand that developing

countries make enormous investments with few results, high debt, and as

seen in this particular case, both economic and environmental losses.

To make the situation worse, frequently these projects are

under-utilized and will generate permanent costs in maintenance and

constant outlays of taxpayers' money."

The affected

social organizations go even further in their criticisms. The Honduran

Black Fraternal Organization (OFRANEH) states: "The five corridors made

up of 13,000 km. that will, according to the designers of the project,

promote connectivity and competition in the region, puts the habitat of

the majority of the indigenous populations in Mesoamerica in danger."

"For the OFRANEH

and the Garífuna people, the Mesoamerican Project is nothing more than

an intervention on our territory, and currently we see how one of the

projects, financed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), is

finishing off the wetlands of Laguna de Micos in Tela Bay, putting

neighboring communities in danger with the filling up of 80 hectares of

wetlands. The situation is exacerbated by climate change that could

bring about fatal flooding."

The Conceptual Framework

The PPP-MIDP

seeks to insert the Mesoamerican region into the global economy,

oriented toward the U.S. market at a time when it is in the throes of a

recession and restructuring. It permanently dismantles small-scale

production activities at the national level in favor of large-scale

foreign investment at a time when foreign investment is contracting and

the environmental and social crises created by this type of development

is becoming more and more obvious and unacceptable. The production

model based on raw materials and extraction activities, prescribed by

multilateral banks for countries in the region, requires expensive

modern mega-infrastructure, paid for in part by developing countries in

crisis that have an enormous social debt with their populations. Much,

if not most, of this price winds up in the pockets of foreign

contractors and investors.

The view of

regional integration from above sees the communities in the region—in

many cases indigenous and campesino communities, like the Mayan Jungle

population and the OFRANEH—as objects and not subjects. The PPP-MIDP

offers a few token production projects and assistance programs for

these communities, separated from and sabotaged by the overall regional

development plan based on foreign investment. In southern Mexico, where

the PPP-MIDP has made inroads in implementation, the indigenous

organization UCIZONI of the Tehuantepec Isthmus reports that these

programs "have had negative results in our communities, since the

negative impacts of foreign investment are not compensated with

government assistance programs. In the current context of cuts in

education, health, and agricultural subsidies, and the deregulation of

investment, it is believed that this negative effect will worsen."

According to the

MIDP vision of regional integration, these local populations are

objects to be manipulated as needed and often simply obstacles to the

designs of transnational investment. Major land-use changes implied in

converting natural forests to monoculture plantations, eliminating

peasant faring, flooding whole communities in dam projects, building

highways through jungles and other sources of natural biodiversity, and

extracting minerals by devastating the natural landscape and human

communities, create a net loss of jobs and push local inhabitants to

migrate.

The Security Issue – The Trojan Horse of PPP-PM Integration

The July summit

in Costa Rica was the second since the beginning of the new

Mesoamerican Project phase. The summit consolidated the integration of

a new issue in the regional integration scheme—security. The Guanacaste

Declaration includes 10 points dedicated solely to the war on drugs and

organized crime. The second of these establishes the direction of this

"war":

Receive with enthusiasm the Merida Initiative as an important

instrument for international cooperation in the fight against

transnational organized crime, in particular drug trafficking, based on

a focus on shared but different responsibilities between the states.

Equally, manifest the desire to increase regional cooperation against

organized crime and the urgency of increased funds for the development

and strengthening of capabilities in each state. In this sense,

reiterate the request made to the government of the United States of

America to increase cooperation resources destined for this issue.

Security issues

were first incorporated into the PPP-MIDP at the 2008 summit. The

Merida Initiative is a regional security plan designed by the

government of George W. Bush to promote the objectives of its National

Security Strategy and counterterrorism model. Mexico's experience with

the Merida Initiative and the "war on drugs" model that it promotes

illustrates the risks and negative impacts of applying this model to

the rest of the Hemisphere. Since its application in 2007 with U.S.

aid, the presence of military troops in Mexican cities and communities

has increased exponentially to 45,000; there is a six-fold rise in

reports of human rights violations by the army; growing levels of

violence have produced 12,300 deaths related to drug trafficking;

interdiction has been reduced by half between 2007 and 2008; and there

has been no evidence that flows of drugs to the U.S. market have

declined. The Merida Initiative includes repressive measures to control

the flow of Central American immigrants and has led to documented

accusations of the criminalization of social protest, with leaders and

members of social movements falsely accused of drug trafficking, drug

production, and terrorism.

The framework

of cooperation within the initiative, which does not include any

obligation on the part of the United States despite being the world's

largest market for illicit drugs and a zone of easy access, allows for

increased operation of U.S. government agents in Mexican territory and

in national agencies key to its national sovereignty including the

military, police forces, intelligence organizations, and the courts.

Instead of promoting an integral analysis of the security problem in

the region, from the perspective of the region itself, the Summit calls

for an extension to this failed model with extreme costs to society in

terms of human rights and civil liberties.

The OFRANEH points out the risks in Central America:

"The Mesoamerican Project is the carrot tied to the Merida Initiative

stick, a local version of Plan Colombia. Drug trafficking and Mara

salvatrucha gang members have become the pretext for the gradual

militarization of the isthmus though the two problems both carry the

visible label 'made in the USA.'"

FTAA Integration Through Infrastructure

The summit also

renewed the relationship between the Mesoamerican infrastructure plan

and the free trade model embodied in the North American Free Trade

Agreement (NAFTA) and its failed expansion, the Free Trade Area of the

Americas (FTAA). One of the points in the declaration was "Reiterate

that economic integration is a path to increased competitiveness for

the countries of the region and in this sense, we congratulate

ourselves with the beginning of a negotiation process to reach a

convergence of the Free Trade Agreements between Costa Rica, El

Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Mexico."

The declaration

ratifies its agreement with the "Paths of Prosperity" process. This

alliance of countries along the Pacific Rim was an invention of the

Bush administration to unite those countries that have free trade

agreements with the United States and consolidate a bloc to undermine

the union of South American nations that have rejected the neoliberal

model. In the last meeting, even Sec. of State Hillary Clinton

questioned the validity of this division based on FTAs, suggesting the

incorporation of other countries, among others, Brazil.

Along the same

lines, the declaration calls for the continuation of the Doha Round,

stating "the conclusion of these negotiations will contribute to the

global economic recovery and increase the benefits of the multilateral

system of trade." It calls for "the elimination of internal

agricultural assistance in developed countries," however it does not

question the uncompensated asymmetries between wealthy countries and

poor ones within the WTO approach that is at the center of the Doha

Round's stagnation. In practical terms, the PPP-MIDP is part of the

revitalization of the FTAA, after having hit a wall of resistance in

the Andean and Southern Cone countries. Despite its fresh makeover, it

is still recognizable. These projects are oriented toward integration

into the global economy at the expense of local communities. It is a

model that offers optimal conditions for foreign capital and

investment, while eroding local communities and real sustainable

development.

CIP Americas Program