Editor's Comment: Read Edward Guthmann's SF Gate report on Simin Marefat, an extraordinary US-Iranian activist for humanity and you will understand why we have selected her as Axis of Logic's next Featured Activist.

- Axis Editors

How Simin Marefat, an unstoppable nurse at UCSF,

aids Africa, one orphan at a time

|

|

Simin Marefat in her San Francisco home, surrounded by photos taken on her more than 60 trips abroad. Chronicle photo by Paul Chinn |

Take a pin, stick it in a map of the world and chances are Simin Marefat has been there. A San Francisco nurse and health care volunteer, she's been to 62 countries - mostly in the Third World. She's fed children and changed diapers in Rwandan orphanages. Delivered babies in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Educated sex workers on HIV prevention in Thailand. Vaccinated children in Pakistani refugee camps. Taught EKG and the care of open-heart patients in her native Iran.

Usually she travels alone and plans nothing in advance. "I would just go and I'd be like, 'I'm a nurse practicing in the United States. I'm here to offer my services.' And they would put me to work."

Today, Marefat is a master’s degree candidate in health policy at the UCSF School of Nursing. During her busiest travel years, she was a per-diem nurse at UCSF and could cluster her shifts and travel often. "I would leave the country every three months and go for, like, a month or six weeks at a time," Marefat, 33, says in the hillside home she bought two years ago in San Francisco's Ingleside district.

Wherever she went, she saw enormous need and a huge deficit of resources. For a long time, Marefat says, she hopscotched the globe: Mali and Cameroon, February 2000; Costa Rica, Honduras and Panama, May 2000; Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan, March 2001; Cuba, October 2003; Vietnam, December 2003; Chile, Argentina, Peru and Bolivia, March 2004; Croatia and Slovenia, August 2006.

"I've traveled the world by myself," says Marefat, who lived in Iran until age 11. "A Middle Eastern woman does not do that."

"She's unstoppable," says her brother Bobby, an ophthalmologist in Topeka, Kan. "Do I worry about her? Yes. Do I try to talk her out of it? Absolutely not, because this is what she loves - it gets her juices flowing."

Marefat is at her dining table, wearing jeans and a black blouse, trying to explain her commitment to the overlooked. "I'm most fulfilled when I know I've helped somebody else," she says. "When I see someone without basic health and education, without a supportive family, I feel a connection. We're all cells of one body."

More than any other country, Rwanda profoundly affected Marefat. In February 2005, 11 years after 800,000 Rwandans were killed in a government-directed genocide that lasted 100 days, Marefat went to the capital, Kigali. She worked in refugee camps and met orphans who'd seen their parents, mostly Tutsis, hacked to death by machete; children who'd hidden in trees during the slaughter and later walked through villages scattered with body parts; children who survived, went to school and longed for a better life.

|

|

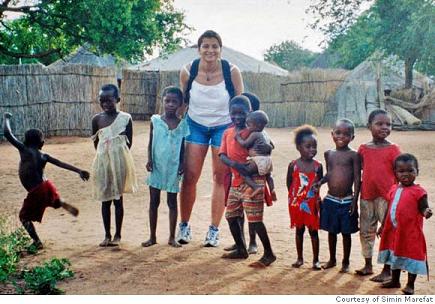

Marefat poses with a group of children she met during a recent trip to Africa. Photo courtesy of Simin Marefat |

According to recent figures, there are 43 million orphans in sub-Saharan Africa. In Rwanda, which lost 10 percent of its population in the genocide, and now has close to 10 million people, there are 600,000 orphans - mostly from the genocide, many also from AIDS and malaria.

In Kigali, Marefat met Oliver Rothschild, a Yale Medical School student who in 2004 founded Orphans of Rwanda with his friend Dai Ellis, a Yale Law School grad who directs the Drug Access Team for the Clinton Foundation HIV/AIDS Initiative. Rothschild, 27, took Marefat to an orphanage called Gisimba Memorial Center - one of the locations, like the Hotel des Milles Collines portrayed in "Hotel Rwanda," that housed and protected Tutsis and moderate Hutus from extremist Hutu militia groups during the genocide.

"I saw the children they were supporting," she says. "The children were not getting health care and when I came home I decided to raise money to provide heath care for them."

Marefat had never organized a benefit before, but in June 2006 she gathered dozens of friends and UCSF colleagues at the Photography Center in Duboce Park. She solicited donations of food and wine from local restaurants, and held a silent auction of photographs taken by her and other photographers. The benefit raised $14,000.

The proceeds helped Orphans of Rwanda to build a health clinic at Gisimba Memorial Center, which Marefat visited in June. "It was wonderful for me to see where the money went, to know that they had done the right thing with it. The children all have health cards with their pictures and vaccinations and medications. They have a nurse who provides for them. The children call her 'Ma-Ma.' They have no parents and she is so compassionate toward them. They love the fact that she hugs them and takes care of them."

In Kigali - a city built on terraced hills, surrounded by banana trees, tea and coffee plantations and eucalyptus - Marefat stayed in the home of Shirley Randell, an Australian woman working on gender-equality and governance issues for the Netherlands Development Agency. She befriended Eustache, the guard at Randell's house, and arranged for his epileptic daughter, who'd been misdiagnosed as having mental illness, to be put on the right medication.

Wherever she went, people were barely getting by. An orphaned brother and sister caught her eye one day - they were living in a ditch under a driveway - so she took them home, bathed them, fed them and arranged for their adoption.

She took an interest in Jackson, one of the government-licensed moto (motor scooter) drivers who function as cabbies, and hired him to drive her to work each morning. Jackson speaks Kinyarwanda, the Rwandan national language, but Marefat learned through a translator that he lived with a woman and their child but wasn't married. He lacked the money to pay for a dowry. "You have to give the woman's family something, either buying them a chicken or a goat or a cow. So I ended up buying him a goat. I paid $50 for it."

|

|

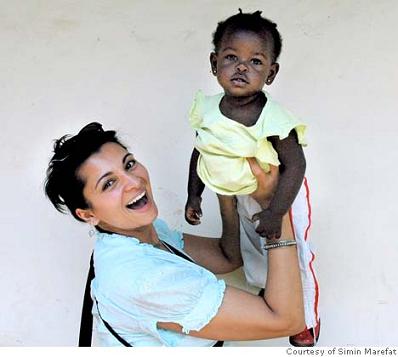

Marefat with an orphan in the clinic in Rwanda.

Photo courtesy of Simin Marefat |

At summer's end, Marefat says, she'd spent $5,000 helping the various people she met. "After, like, being there two months I'm thinking to myself, 'Oh my God, I have a home. I have responsibilities. I can't just shell out money.' It's like, 'When do I stop?' You see these people and you want to do more and more."

In the 14 years since the Rwandan genocide, dozens of international service organizations have worked to heal and rebuild the tiny nation, among them Population Services International, Family Health International, Women Waging Peace and CARE. The Clinton Foundation's HIV/AIDS Initiative is working with Dr. Paul Farmer's Partners in Health, an international health and social justice organization, to upgrade the country's health care system and stem the rate of HIV infection. In 2005 they rebuilt Rwinkwavu Hospital, a derelict facility in southern Rwanda that lacked water and electricity.

Orphans of Rwanda is one of many NGOs and nonprofits trying to rebuild the country, but it's the only one raising scholarship money to send Rwandan orphans to university. Michael Brotchner, 34, is the organization's New York-based executive director. Like Marefat, he's whip-smart, speaks rapidly and exudes an urgency and commitment that seem to say, "OK, let's do it ... now!"

"I met Simin in Kigali last summer, over lunch at somebody's house," Brotchner said during a visit to San Francisco. "I'd heard all about her, this great volunteer who did all this great stuff. And when I met her I said, 'Oh! You're the famous Simin.' First of all she shows me her photos. I honestly think she is the best non-professional photographer I've ever seen. Just ridiculously good.

"I said to her, 'Simin, let's do another event in San Francisco,' and she said, 'Sign me up.' " Marefat spearheaded a second ORI benefit, held in November at the Herbst Exhibition Hall in the Presidio, where the guest speaker was Farmer, who is also an infectious disease specialist, and the subject of Tracy Kidder's book "Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, the Man Who Would Cure the World." Four hundred people attended, Marefat's photographs were again auctioned and the benefit raised $18,000.

That amount will cover tuition for nearly half of the recently selected 68 ORI scholarship students who started school last month. In addition to tuition, which runs approximately $550 per student per year, an ORI scholarship includes housing expenses and health care, a monthly living stipend and computer and language training.

"We send extremely talented orphans to college and in one sense that's great for them as individuals," Brotchner says. "In a larger sense, we're trying to build human capital in Rwanda. One in 200 Rwandans go to college and this country is trying to go from an agricultural economy to a modern knowledge-based economy. And they're not going to be able to do that without getting these highly trained individuals. So we're taking the most vulnerable people in society and giving them a chance to build a future in their country."

"She's extremely dedicated," Brotchner says of Marefat. "I think she sees the big-picture, policy, macro stuff. But she's also very, very interested in the individual lives of the students. "

She's also energetic - amazingly so. "All of Simin's friends have stories about phone calls you get where she's gathered all this information for you and leaves it on your voicemail," says Julie Cuccia, a UCSF nurse and friend who joined Marefat in Rwanda last summer.

"She's Valium-deficient!" says her brother Bobby. "I'm kidding. But she doesn't tire. She's a little scary, she really is."

She's also courageous. It's the result, Marefat says, of fleeing Iran at 11; of relocating to the United States, learning a new culture and knowing that, because she was Iranian, she was unwelcome.

In Iran, Marefat lived in Shiraz, a city in the southwest, and spent summers on the Caspian Sea, at her great-uncle's beachside villa. "Everyone, all my cousins, would be there - 30 people. Our parents would cook and the kids would be on the beach playing, building sand castles. The water was the color of turquoise. At night we'd build a fire and one of my other uncle's wives would sing."

Everything ended when Marefat's father, an oil engineer known for his strong opinions, said something that offended the government. Marefat is careful not to reveal too much, but says it took two years to find a reliable guide to transport the family into Turkey from Iran: "There were stories that you would pay people and they would take you across the border and kill you."

In 1986, Marefat, her brother and parents said goodbye to their relatives and flew from Tehran to Tabriz in the northwestern corner of Iran. "It ended up that my uncle had a friend who knew someone whose son was taken out of the country by this gentleman, a Kurd." In Tabriz, "we waited until they called and said, 'Today's the day to go.' And they pick you up on a street corner."

It took three days to cross the Zagross mountains into Turkey. They went by foot, by donkey and motor scooter through Kurdish territory - traveling by night. The family had no luggage, "just the clothes on our back. My mother had ripped apart our belts and put money in and sewed them back up. The heels of our shoes were opened and money was put in there and resealed."

In Istanbul, the American Embassy was seeing hundreds of Iranian refugees. The Marefats were granted political asylum and visas to live in the United States - in part because Simin's father went to college in the United States and her brother was born here. "We ended up in Kansas because the house where my parents had lived while my dad was in college was available. They'd stayed in touch with the landlord and he said to them, 'Why don't you come here? It's safe, it's cheaper.' So we ended up in Hays, Kansas."

Unable to find work as an engineer or academic, Marefat's father opened a restaurant, Maxim's. "We didn't serve Middle Eastern dishes. Just American food. Really basic: meatballs, Salisbury steak, meat loaf, chicken tetrazzini. I washed dishes and helped my Mom prepare food. I worked there from when I was 11 until I was 21."

The whole family worked at Maxim's, in her parents' case from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m., seven days a week. The restaurant succeeded, Marefat says, "(But) it was hard for me, because my parents are so educated, to see them work like that. I always wonder what went through my dad's mind when he waited on tables."

Even today, Marefat speaks English in an accent hybridized from Farsi and the hard, flat consonants of Kansas. When her family arrived in the United States, it was 1986. The Iran hostage crisis of 1979-81, when 52 U.S. citizens and diplomats were held hostage in Tehran for 444 days, was fresh in people's minds. In Hays, a small town of 26,000 residents, originally settled by German immigrants, Iranians were treated at best as oddities, and more often as intruders.

"My brother and I got teased in school all the time. Kids were really mean. And my parents had things told to them like, 'You shouldn't be here.' But the beauty of it was that, having gone through all that, to see how the town fell in love with my parents and how they are now so respected in the community."

It was that odyssey, beginning with escape, displacement, discrimination and eventual acceptance, Marefat says, that taught her anything was possible. She earned her nursing degree at Fort Hays State University in Hays, left Kansas at 21 and worked in Texas, San Diego, Seattle and Hawaii before moving to San Francisco in 2000.

When asked how she makes time for romance, she looks embarrassed. "There's not a lot of people who have gone to some of the places that I've gone and seen some of the things that I've seen. Hopefully, there will be somebody who will understand it and think it's great and will be proud to stand next to me. But, you know, they obviously haven't been the right people (so far), because they didn't support what I'm so passionate about.

"I definitely think I can find a balance. I've lived in this country and I've still affected change in Africa. I can do it from here. I am doing it from here."

Marefat will finish her master's in June, at which point she hopes to find a one- or two-year AIDS-policy position in Africa. Combining nursing and health-policy administration, she says, is unique: Whereas many policymakers haven't been in the field, seen a refugee camp or worked in an HIV clinic, Marefat has done all of that. She's seen the direct impact of policy, for better and for worse, on the lives of the people.

She has no plans to stop working as a nurse. "I can always volunteer on the weekends at the clinics or hospitals (in Africa). I love the patient interaction. I love the people and meeting them and hearing their stories and things of that sort.

"Why can't I do both?"

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/02/03/CMCQTSTAD.DTL&hw=ucsf+nurse&sn=001&sc=1000

E-mail the author of this SFG article -

Edward Guthmann at eguthmann@sfchronicle.com.